Christopher alexander - A pattern language

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher alexander - A pattern language» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Прочая научная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A pattern language

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A pattern language: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A pattern language»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A pattern language — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A pattern language», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Communities can only get this personal quality back if they prohibit all forms of franchise and chain stores, place limits on

the actual size of stores in a community, and prohibit absentee owners from owning shops. In short, they must do what they can to keep the wealth generated by the local community in the hands of that community.

Even then, it will not be possible to maintain this pattern unless the size of the shop spaces available for rent is small. One of the biggest reasons for the rise of large, nationally owned franchises is that the financial risks of starting a business are so enormous for the average individual. The failure of a single owner’s business can be catastrophic for him personally; and it happens, in large part because he can’t afford the rent. Many hundreds of tiny shops, with low rents, will keep the initial risk for a shop keeper who is starting, to a minimum.

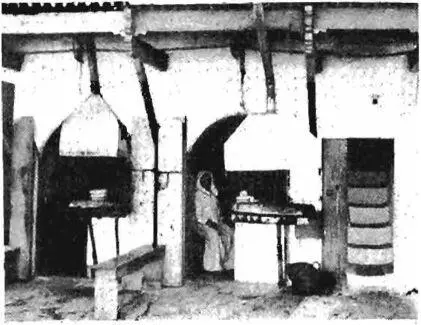

Shops in Morocco, India, Peru, and the oldest parts of older towns, are often no more than 50 square feet in area. Just room for a person and some merchandise—but plenty big enough.

|

| Fifty square feet. |

Therefore:

Do what you can to encourage the development of individually owned shops. Approve applications for business licenses only if the business is owned by those people who actually work and manage the store. Approve new commercial building permits only if the proposed structure includes many very very small rental spaces.

434

INDIVIDUALLY OWNED SHOPS

| owner occupied |

|---|

|

| ' - • T-* I • V— ; |

some no more than 50 square feet4* »!♦

Treat each individual shop as an identifiable unit of a larger building complex (95); make at least some part of the shop part of the sidewalk, so that people walk through the shop as they are going down the street—opening to the street (165); and build the inside of the shop with all the goods as open and available as possible—the shape of indoor space (191), thick WALLS ( I 97), OPEN SHELVES (200) . . . .

435

TOWNS

process which we believe is compatible with this piecemeal approach.

1. The core of the planning process we propose is this: The region is made up of a hierarchy of social and political groups, from the smallest and most local groups —families, neighborhoods, and work groups—to the largest groups—city councils, regional assemblies.

Imagine for example a metropolitan region composed very roughly of the following groups, each group a coherent political entity:

A. The region: 8,000,000 people.

B. The major city: 500,000 people.

C. Communities and small towns: 5-10,000 people each.

D. Neighborhoods: 500-1000 people each.

E. House clusters and work communities: 30-50 people each.

F. Families and work groups: 1-15 people each.

2. Each grouf makes its own decisions about the environment it uses in common. Ideally, each group actually owns the common land at its "level.” And higher groups do not own or control the land belonging to lower groups—they only own and control the common land that lies between them, and which serves the higher group. For instance, a community of 7000 might own the public land lying between its component neighborhoods, but not the neighborhoods themselves. A co-operative house cluster would own the common land between the houses, but not the houses themselves.

3. Each of these groups takes responsibility for those patterns relevant to its own internal structure.

Thus, we imagine, for example, that the various

4

| 88 STREET CAFE** |

|---|

|

436

. . . neighborhoods are defined by identifiable neighborhood (14); their natural points of focus are given by activity nodes (30) and small public squares (61). This pattern, and the ones which follow it, give the neighborhood and its points of focus, their identity.

*£•

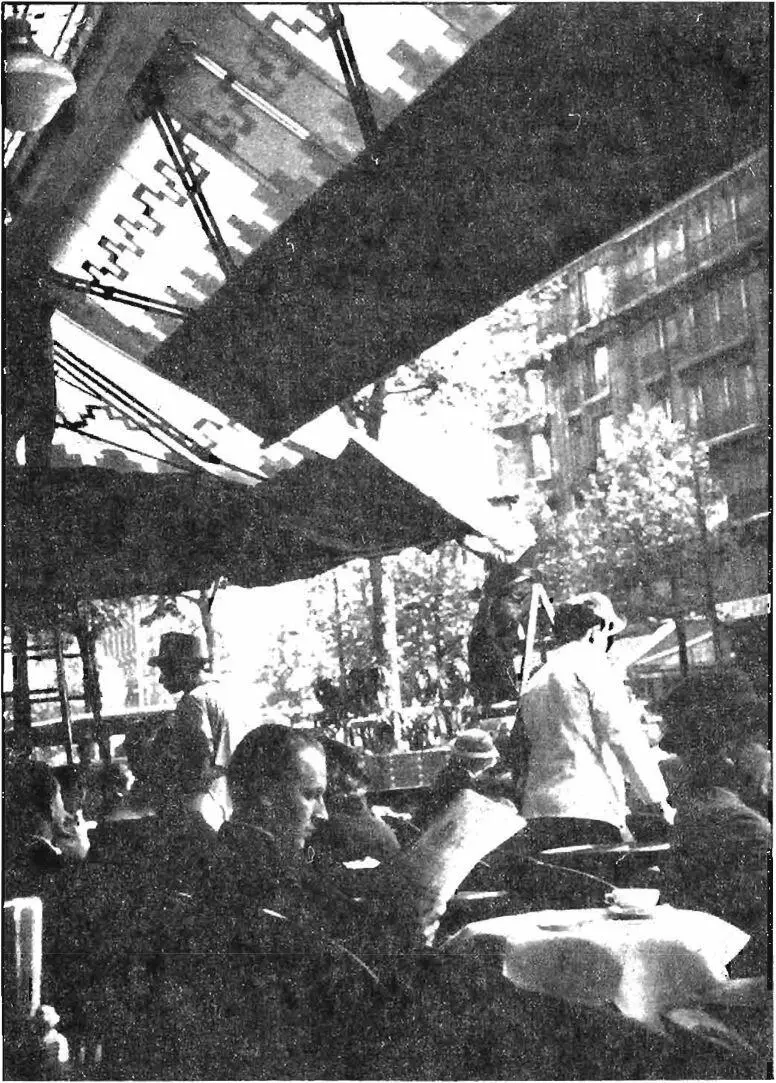

The street cafe provides a unique setting, special to cities: a place where people can sit lazily, legitimately, be on view, and watch the world go by.

The most humane cities are always full of street cafes. Let us try to understand the experience which makes these places so attractive.

We know that people enjoy mixing in public, in parks, squares, along promenades and avenues, in street cafes. The preconditions seem to be: the setting gives you the right to be there, by custom; there are a few things to do that are part of the scene, almost ritual: reading the newspaper, strolling, nursing a beer, playing catch; and people feel safe enough to relax, nod at each other, perhaps even meet. A good cafe terrace meets these conditions. But it has in addition, special qualities of its own: a person may sit there for hours—in public! Strolling, a person must keep up a pace; loitering is only for a few minutes. You can sit still in a park, but there is not the volume of people passing, it is more a private, peaceful experience. And sitting at home on one’s porch is again different: it is far more protected; and there is not the mix of people passing by. But on the cafe terrace, you can sit still, relax, and be very public. As an experience it has special possibilities; “perhaps the next person . . .”; it is a risky place.

It is this experience that the street cafe supports. And it is one of the attractions of cities, for only in cities do we have the concentration of people required to bring it off. But this experience need not be confined to the special, extraordinary parts of town. In European cities and towns, there is a street cafe in every neighborhood—they are as ordinary as gas stations are in the United

States. And the existence of such places provides social glue for the community. They become like clubs—people tend to return to their favorite, the faces become familiar. When there is a successful cafe within walking distance of your home, in the neighborhood, so much the better. It helps enormously to increase the identity of a neighborhood. It is one of the few settings where a newcomer to the neighborhood can start learning the ropes and meeting the people who have been there many years.

The ingredients of a successful street cafe seem to be:

1. There is an established local clientele. That is, by name, location, and staff, the cafe is very much anchored in the neighborhood in which it is situated.

2. In addition to the terrace which is open to the street, the cafe contains several other spaces: with games, fire, soft chairs, newspapers. . . . This allows a variety of people to start using it, according to slightly different social styles.

3. The cafe serves simple food and drinks—some alcoholic drinks, but it is not a bar. It is a place where you are as likely to go m the morning, to start the day, as in the evening, for a nightcap.

When these conditions are present, and the cafe takes hold, it offers something unique to the lives of the people who use it: it offers a setting for discussions of great spirit—talks, two-bit lectures, half-public, half-private, learning, exchange of thought.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A pattern language»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A pattern language» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A pattern language» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.