War Isn’t Just about Guns and Bombs: When Ideas Kill

War is often motivated by more than dispassionate logic. Pride, fear, and hatred can mobilize an enemy far more effectively than a cold cost-benefit analysis.

Historically, most of the United States’ foes have been driven not by rational motivations but by extreme ideologies. The Barbary pirates who terrorized American commercial shipping in the Mediterranean so soon after the Revolutionary War were just such a group. So were Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich and Stalin’s Soviet Union. Each regime was defined by an extreme, absolutist, and totalitarian ideology, as are Iran and North Korea today.

It is clear that a group like al-Qaeda, with its suicide bombers, or the Islamic State, with its goal of a global caliphate, is not a “rational” nation-state actor with conventional political interests corresponding to the Clausewitzian concept of war.

How do you deal with a foe who does not reason as you do? What is the role of force when facing an ideologically committed enemy, be it a unit of Nazi SS, the Viet Cong, or the 9/11 hijackers? Are there better options than all-out war against such an enemy? Perhaps there is no universal template for defeating such adversaries, but there are lessons to be learnt from America’s past experience with totalitarian regimes and ideologically-motivated extremist groups.

If the threat from an enemy driven by a violent ideology is imminent and existential, there may be no alternative to large-scale conventional war. Nazi Germany posed such a threat.

WORLD WAR II: WAR FOR CIVILIZATIONAL SURVIVAL

The inability or unwillingness of European nations to challenge Hitler’s rearming of Germany in the 1930s encouraged his territorial demands in the Sudetenland and the annexation of Austria. Once the Third Reich began its blitzkrieg across Europe, the response had to be one of tanks, infantry, bombers, fighter aircraft, and naval vessels. After Hitler’s ally Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, this became a true “world” war as the United States eventually deployed more than twelve million fighting men to liberate Europe from the Nazis’ ideology of Aryan racial supremacy and Asia from General Tojo’s imperialism.

Although this global conflict would end only when the United States became the first nation to use nuclear weapons, World War II was not solely a war of tank divisions destroying tank divisions, of submarines hunting aircraft carriers, or fighter planes in aerial dogfights. A large part of the conflict involved the mind, not bullets or bombs. This was the propaganda war, and America became very good at “non-kinetic conflict.”

WARS OF THE MIND

Clausewitz was correct that all war is a battle of wills. Propaganda has an important role to play in all conflicts since each side desires to influence the behavior and attitude of both its own people and those it wishes to defeat. The importance of propaganda grows when the enemy mobilizes its forces not simply to capture territory, increase its wealth, or avenge to a perceived injury, but in pursuit of an ideology that sees others as subhuman and for populations to be annihilated or subjugated, as was the case with Hitler’s Nazi Reich.

Even in ostensibly conventional conflicts such as the first and second world wars, propaganda plays a crucial role. How successfully a nation contrasts itself and its military objectives to the enemy and the enemy’s values strongly affects the duration and the human and economic costs of the war.

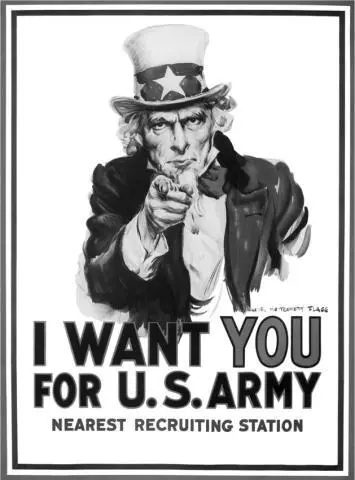

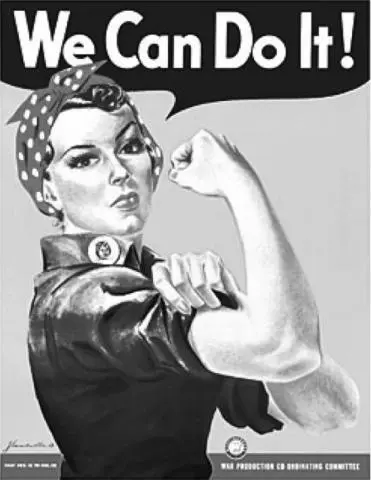

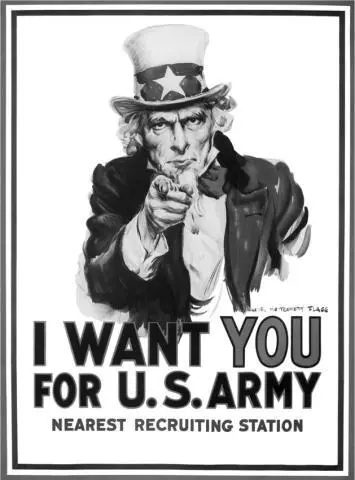

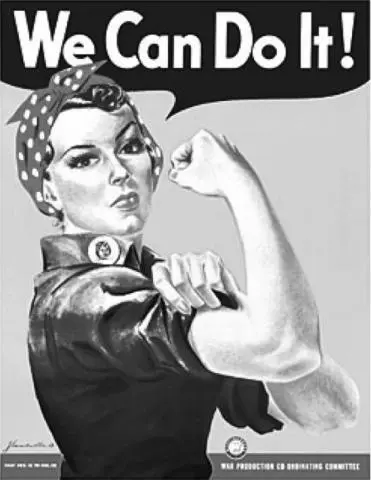

If carried out effectively, such non-kinetic “operations” can rouse a nation, undermine the forces of its adversary, and win over or deter the fence-sitters. The US Army’s “I want you” recruiting poster, with its stern Uncle Sam pointing at the viewer, is among the most famous images in American history; more than four million were printed during World War I. Another is World War II’s Rosie the Riveter urging American women on the home front with the slogan, “We Can Do It!”

Illustration 1: Perhaps the Most Famous Propaganda Poster

Illustration 2: Perhaps the Second-Most Famous Propaganda Poster

FROM PROPAGANDA TO MILITARY INFORMATION SUPPORT OPERATIONS

Today the word “propaganda”—Latin for “propagating”—has a pejorative connotation, suggesting communication that is tendentious and manipulative, but this was not its original sense. The word entered the English language in 1622 when Pope Gregory XV established the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide —the Congregation for Propagating the Faith—originally referring simply to activities that spread certain ideas amongst a given population. There was no suggestion of compulsion, deceit, or that the ideas were less than wholesome. The sinister sense that colors the word today is a product of the political history of the twentieth century, especially its association with two world wars and the totalitarian ideologies of fascism, Nazism, and communism.

Although arguments persist as to how “propaganda” should be defined, a simple and accurate interpretation would be: non-physical activities aimed at a specific audience with the intent of altering attitudes, behavior, or both.

To distance this important mission from the unpleasant and offensive propaganda of Hitler’s fascist state and the former Soviet Union, today’s national security establishment uses more modern labels for non-kinetic, information-based activities that support military objectives or broader national interests. These include:

• information operations

• strategic communications

• influence operations

• psychological operations

The last is often shortened to “PSYOP,” or diluted into the dry-sounding Military Information Support Operations, or “MISO.” The US Army Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg has at its disposal whole units whose mission is to use information in the battlefield directly against the enemy and win over local populations to the side of our forces or our allies’ and partners’ forces.

When attempting to strike the balance between military force and non-physical means to secure the country and realize national security objectives, it is useful to remember the grand strategist Sun Tzu’s definition of the perfect victory: winning without fighting. How can this be done? How can you win without employing violence? By convincing your adversary—be it a country, terrorist group, or an insurgency—that it cannot defeat you or that its victory will be too costly.

You can also win the “battle of wills” if your adversary is convinced that its own values are bankrupt and yours are superior. This may sound impossible, but there is a twentieth-century example of a victory against a deadly foe won without ever firing a shot. This victory is of more than merely historical interest. Indeed, it is a case study of renewed importance for an age in which the general public is increasingly “gun-shy” of “adventurist” military operations abroad while the internet provides us and our enemies with a vast new arena for “influence operations.”

WINNING WITHOUT FIGHTING: IDEOLOGICAL WARFARE AND THE COLD WAR

When the United States entered World War II, it joined the Soviet Union as an ally despite the Russians having signed a secret nonaggression pact with Hitler before the war which facilitated the carving up of Poland by the Third Reich and USSR. When Hitler betrayed the Kremlin and invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Moscow became a de facto ally of the West. This alliance between the Soviets and America, however, would not endure.

Читать дальше