In a landmark work written more for the interested layman than the national security professional or the policy expert, the late British historian John Keegan laid down a comprehensive challenge to Clausewitz’s consensus. Keegan, who wrote many works on the history of war and great military leaders, opens his famous book, A History of Warfare, defiantly: “War is not the continuation of policy by other means.” He continues:

[W]ar antedates the state, diplomacy and strategy by many millennia. Warfare is almost as old as man himself, and reaches into the most secret places of the human heart, places where self dissolves rational purpose, where pride reigns, where emotion is paramount, where instinct is king.

Today, experts and scholars are divided between those who consider Clausewitz’s analysis enduringly valid—a camp most ably led by the British strategist Colin Gray—and those, best typified by the Israeli author Martin van Creveld, who see Clausewitz’s relevance as limited to nation-against-nation conflicts, such as World War II, and having little to say about today’s messier conflicts.

This argument will likely persist for some time. It is, however, instructive to assess what kinds of wars we have fought in recent centuries and what that experience can tell us about the wars America will have to fight in the future.

WAR: PAST AS PROLOGUE

In 1963, a professor at the University of Michigan took up the monumental task of collecting all the key data from all the conflicts and wars since the time of Napoleon. The resulting database, the Correlates of War Project now based at Penn State, is still being assembled today. This treasure trove of information is invaluable to anyone who wants to identify patterns and trends in war and peace over the last two centuries. And if you take the time to categorize the wars that the database contains, one remarkable fact stands out.

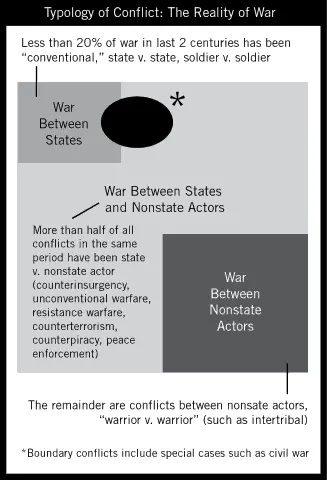

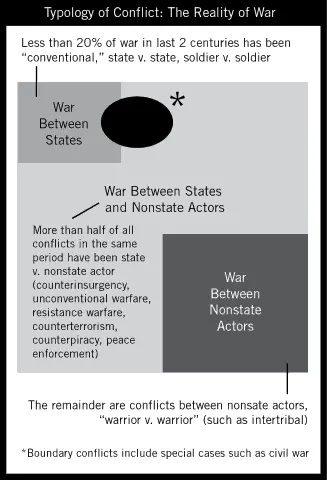

According to the project’s definition, there have been more than 460 wars or armed conflicts since the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. If you divide those conflicts into three groups—wars fought between countries, wars fought between countries and non-state groups or sub-state actors, and wars fought solely between non-state actors—you get a figure like this:

Types of War since 1815 (Based on data from the Correlates of War Project)

Specifically, of the 460 wars since Napoleon, less than twenty percent have been what we commonly understand as “conventional war,” regularized conflicts between the uniformed armed forces of two or more opposing governments. More than 380 have involved the armed forces of a nation against an enemy that did not represent another country or government—a group like al-Qaeda, for example—or did not involve regular national armed forces at all, such as tribes fighting against each other. The empirical data therefore supports a critique of the Clausewitzian depiction of war as a rational enterprise carried on by the nation-state.

Keegan argues that war is rarely the result of reasoned calculation. Most often, war is fought for social and cultural reasons by non-state actors, often simply to assert one’s identity in opposition to another group. To anyone who takes a look at the history of the Unites States from the longer perspective, the disproportionate ratio of non-traditional warfare to “regular” state-on-state war should not come as a surprise.

In the Pentagon’s Hall of Heroes, the names of the more than three thousand Medal of Honor recipients are inscribed along the walls, each name listed under the campaign in which the honor was earned. Only five of the seventeen campaigns represented could be described as traditional state-on-state wars fought by regular armed forces fielded by their respective governments. These wars include World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. The other dozen conflicts are far from conventional, ranging as they do from our nation’s involvement with the Boxer Rebellion in China to the Global War on Terror.

A more complete list of America’s military conflicts—not just those in which the Medal of Honor was awarded—would look like this:

| CONFLICT |

Date |

| American Revolution |

1775-1783 |

| Barbary Campaigns |

1801-1805 |

| 1815-1816 |

| War of 1812 |

1812-1815 |

| American Indian Wars |

c. 1817-1898 |

| Mexican War |

1846-1848 |

| Civil War |

1861-1865 |

| Spanish-American War |

1898-1902 |

| Samoan Civil War |

1898–1899 |

| Boxer Rebellion |

1900-1901 |

| First Haitian Campaigns |

1915-1934 |

| CONFLICT |

Date |

| Dominican Campaign |

1916-1924 |

| World War I |

1917-1918 |

| Nicaragua Campaign |

1926-1933 |

| World War II |

1941-1945 |

| Korean War |

1950-1953 |

| Vietnam War |

1964-1975 |

| El Salvador |

1980-1982 |

| Afghanistan Operation Cyclone |

1979-1989 |

| Desert Shield/Storm |

1990-1991 |

| Colombia |

1990-1994 |

| CONFLICT |

Date |

| Balkans |

1992-1994 (UN/NATO) |

| 1995 (Deliberate Force) |

| Somalia Action |

1993 |

| Haiti Operation Uphold Democracy |

1994–1995 |

| Kosovo Campaign |

1999 |

| Operation Enduring Freedom |

2001-2014 |

| Operation Iraqi Freedom |

2003-2011 |

| Operation Inherent Resolve (Counter ISIS) |

2014- |

Even when the full list is categorized and we allow boundary conflicts as such as the Vietnam War to be counted in both the conventional and unconventional categories, it is obvious that irregular wars are in fact not irregular, but more common than the adjective would have you believe. The United States has fought in fifteen conventional and twelve unconventional conflicts—a fairly even split.

Additionally, it is worth remembering that one of America’s earliest conflicts was the campaign against the pirates of the Barbary Coast, who bear a striking ideological resemblance to the Islamic jihadists of today’s al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. The establishment of America as a free country was the result of a war in which irregular, often non-uniformed fighters waged a revolutionary campaign against the conventional, red-coated forces of the imperial government of Great Britain. In other words, the founding of the United States was the direct result of an eminently un-Clausewitzian war.

In light of the global data on war in the past two hundred years, and in particular, America’s own history, it seems that we should reappraise the labels we use and rethink what kinds of wars we can expect to fight in the future.

The US military and the Pentagon use the term “conventional war” to describe conflicts like the First Gulf War or World War II, in which soldiers fight soldiers and tanks fight tanks. These are deemed to be “real” wars as opposed to “irregular” or “unconventional” wars, which are treated as anomalies to be handled by a small, elite group of fighters such as Army Special Forces (the “Green Berets”) or their tri-service equivalents.

But why is this the case? Why do we officially call that which is more common “irregular” and that which is less common “unconventional”? Could this confusion explain some of our past military failures such as Vietnam?

Читать дальше