Ultimately, every language, including English, demonstrates its culture’s relationship to power by how it chooses to define the act of disclosure. Even the nautically derived English words that seem neutral and benign frame the act from the perspective of the institution that perceives itself wronged, not of the public that the institution has failed. When an institution decries “a leak,” it is implying that the “leaker” damaged or sabotaged something.

Today, “leaking” and “whistleblowing” are often treated as interchangeable. But to my mind, the term “leaking” should be used differently than it commonly is. It should be used to describe acts of disclosure done not out of public interest but out of self-interest, or in pursuit of institutional or political aims. To be more precise, I understand a leak as something closer to a “plant,” or an incidence of “propaganda-seeding”: the selective release of protected information in order to sway popular opinion or affect the course of decision making. It is rare for even a day to go by in which some “unnamed” or “anonymous” senior government official does not leak, by way of a hint or tip to a journalist, some classified item that advances their own agenda or the efforts of their agency or party.

This dynamic is perhaps most brazenly exemplified by a 2013 incident in which IC officials, likely seeking to inflate the threat of terrorism and deflect criticism of mass surveillance, leaked to a few news websites extraordinarily detailed accounts of a conference call between al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri and his global affiliates. In this so-called conference call of doom, al-Zawahiri purportedly discussed organizational cooperation with Nasser al-Wuhayshi, the leader of al-Qaeda in Yemen, and representatives of the Taliban and Boko Haram. By disclosing the ability to intercept this conference call—that is, if we’re to believe this leak, which consisted of a description of the call, not a recording—the IC irrevocably burned an extraordinary means of apprising itself of the plans and intentions of the highest ranks of terrorist leadership, purely for the sake of a momentary political advantage in the news cycle. Not a single person was prosecuted as a result of this stunt, though it was most certainly illegal, and cost America the ability to keep wiretapping the alleged al-Qaeda hotline.

Time and again, America’s political class has proven itself willing to tolerate, even generate leaks that serve its own ends. The IC often announces its “successes,” regardless of their classification and regardless of the consequences. Nowhere in recent memory has that been more apparent than in the leaks relating to the extrajudicial killing of the American-born extremist cleric Anwar al-Aulaqi in Yemen. By breathlessly publicizing its drone attack on al-Aulaqi to the Washington Post and the New York Times , the Obama administration was tacitly admitting the existence of the CIA’s drone program and its “disposition matrix,” or kill list, both of which are officially top secret. Additionally, the government was implicitly confirming that it engaged not just in targeted assassinations, but in targeted assassinations of American citizens. These leaks, accomplished in the coordinated fashion of a media campaign, were shocking demonstrations of the state’s situational approach to secrecy: a seal that must be maintained for the government to act with impunity, but that can be broken whenever the government seeks to claim credit.

It’s only in this context that the US government’s latitudinal relationship to leaking can be fully understood. It has forgiven “unauthorized” leaks when they’ve resulted in unexpected benefits, and forgotten “authorized” leaks when they’ve caused harm. But if a leak’s harmfulness and lack of authorization, not to mention its essential illegality, make scant difference to the government’s reaction, what does? What makes one disclosure permissible, and another not?

The answer is power. The answer is control. A disclosure is deemed acceptable only if it doesn’t challenge the fundamental prerogatives of an institution. If all the disparate components of an organization, from its mailroom to its executive suite, can be assumed to have the same power to discuss internal matters, then its executives have surrendered their information control, and the organization’s continued functioning is put in jeopardy. Seizing this equality of voice, independent of an organization’s managerial or decision-making hierarchy, is what is properly meant by the term “whistleblowing”—an act that’s particularly threatening to the IC, which operates by strict compartmentalization under a legally codified veil of secrecy.

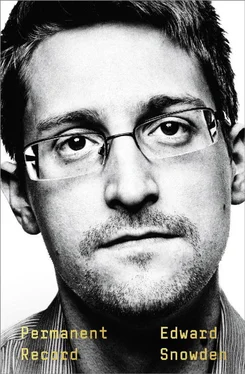

A “whistleblower,” in my definition, is a person who through hard experience has concluded that their life inside an institution has become incompatible with the principles developed in—and the loyalty owed to—the greater society outside it, to which that institution should be accountable. This person knows that they can’t remain inside the institution, and knows that the institution can’t or won’t be dismantled. Reforming the institution might be possible, however, so they blow the whistle and disclose the information to bring public pressure to bear.

This is an adequate description of my situation, with one crucial addition: all the information I intended to disclose was classified top secret. To blow the whistle on secret programs, I’d also have to blow the whistle on the larger system of secrecy, to expose it not as the absolute prerogative of state that the IC claimed it was but rather as an occasional privilege that the IC abused to subvert democratic oversight. Without bringing to light the full scope of this systemic secrecy, there would be no hope of restoring a balance of power between citizens and their governance. This motive of restoration I take to be essential to whistleblowing: it marks the disclosure not as a radical act of dissent or resistance, but a conventional act of return—signaling the ship to return back to port, where it’ll be stripped, refitted, and patched of its leaks before being given the chance to start over.

A total exposure of the total apparatus of mass surveillance—not by me, but by the media, the de facto fourth branch of the US government, protected by the Bill of Rights: that was the only response appropriate to the scale of the crime. It wouldn’t be enough, after all, to merely reveal a particular abuse or set of abuses, which the agency could stop (or pretend to stop) while preserving the rest of the shadowy apparatus intact. Instead, I was resolved to bring to light a single, all-encompassing fact: that my government had developed and deployed a global system of mass surveillance without the knowledge or consent of its citizenry.

Whistleblowers can be elected by circumstance at any working level of an institution. But digital technology has brought us to an age in which, for the first time in recorded history, the most effective will come up from the bottom, from the ranks traditionally least incentivized to maintain the status quo. In the IC, as in virtually every other outsize decentralized institution that relies on computers, these lower ranks are rife with technologists like myself, whose legitimate access to vital infrastructure is grossly out of proportion to their formal authority to influence institutional decisions. In other words, there is usually an imbalance that obtains between what people like me are intended to know and what we are able to know, and between the slight power we have to change the institutional culture and the vast power we have to address our concerns to the culture at large. Though such technological privileges can certainly be abused—after all, most systems-level technologists have access to everything—the highest exercise of that privilege is in cases involving the technology itself. Specialist abilities incur weightier responsibilities. Technologists seeking to report on the systemic misuse of technology must do more than just bring their findings to the public, if the significance of those findings is to be understood. They have a duty to contextualize and explain—to demystify.

Читать дальше