The Kremlin is following exactly the same logic of the Potlatch. The first sacrifice was of sick children. Next was the Russian rouble and the prospects of economic growth. Finally, sanctioned foodstuffs were cast into the sacred hecatomb. All this, apparently, has been done to demonstrate the greatness and sovereignty of Russia, its special path, fortitude and disdain for material values.

The French writer and philosopher, Georges Bataille, has called the Potlatch a political and economic expenditure, which is the opposite of the economy of consumption and accumulation. It is a particular religious action that crosses borders and prohibitions, an ecstatic spectacle of death, like the corrida. We are reminded about our own frailties and about the moment when man finally casts off his material shell. In contemporary Russia, the demonstrative destruction of food products is a move from the conspicuous consumption of the oil era to the demonstrative destruction of the post-Crimea era. Being unable to change the world, Russia is trying to frighten it: it is calling up the spirits of the past, digging out the tomahawks and painting its face with mud. It is burning cheese, crushing the carcases of geese and waving its missile at the world.

All we need to do now is wait for the anthropologists.

Among the losses of recent years – the free press, fair elections, an independent court – what has hurt especially has been the disappearance of good cheese. As Oscar Wilde said, ‘Give me the luxuries and I can dispense with the necessities’; and right now, most of all, we have a shortage of luxuries. Going into the supermarket, I plan my route so that I don’t inadvertently walk past the shelves holding Russian-made cheese, because the bright packaging with the pseudo-European names brings on mild signs of nausea: ‘Maasdamer’, ‘Gruntaler’, ‘Berglander’. And underneath this colourful packaging are concealed tasteless blocks, which are a mix of soap, plastic and the Russian national product – palm oil. If you wanted to point out one place to illustrate the fantastic failure of the policy of import substitution, then look no further than the cheese shelves.

This is reminiscent of the writer Vladimir Sorokin, a visionary genius, who foresaw it in his anti-utopian novel, Day of the Oprichnik . In a totalitarian future in Russia, all foreign supermarkets have been closed down and in their place stand Russian kiosks, in which there are just two types of each item: ‘Russia’ brand cheap papirosi cigarettes and ‘Motherland’ ( Rodina ) cigarettes; Rzhanaya (rye) vodka and Pshenichnaya (wheat) vodka; white bread and dark bread; apple jam and plum jam – ‘Because our God-bearing people should choose from two things, not from three or thirty-three.’ The only product of which there is but one type is cheese – Russian, and the oprichnik , the officer of the security services, struggles in vain to come to terms with the deep and meaningful thought: ‘Why is it that all the goods are in pairs, like the beasts on Noah’s Ark, but there’s only one kind of cheese, Russian?’ [13] Vladimir Sorokin, ‘Day of the Oprichnik ’ (Penguin Books, 2018; trans. Jamey Gambrell, p. 129).

There is a logic to the Russian state’s war on cheese, which is understandable and culturally determined. For the state, cheese is a marker of the dangerous Other , a symbol of the decaying West. It is the rot and the mould of that fluid urban class, which, having travelled around Europe, has come to think too highly of itself and demanded not only cheese but also honest elections; and these people went out onto the streets in December 2011, on Chistoprudny Boulevard and Bolotnaya Square, protesting about the falsified elections for the Duma. There is a direct route from ‘Maasdam’ cheese to ‘Maidan’, as the Ukrainian Revolution was called, and evil must be destroyed at its root – at the customs border of the Russian Federation.

If we analyse this, quality European cheese belongs in the territory of the sensible middle class, because it falls into the category of democratic, affordable refinement. Cheese is not one of those luxuries that can be shown off, like Louboutin shoes and lobsters, Breguet watches and Bugatti cars. Russian sales in this particular consumer market have not fallen off in the time of sanctions. Parking his Porsche Cayenne outside the shabby entrance to his crumbling Soviet-era block of flats and buying foie gras and XO cognac to enjoy in his tiny eight-square-metre kitchen, the Russian man can feel that he is taking part in the cargo-cult of the consumer, that he is in communion with civilization: but he has not become a part of it. But a piece of French brie, a bottle of Italian chianti and a warm baguette in a paper bag from a local bakery drew him close to Western values and were acts of social modernization.

Removing cheese from this formula broke the model of consumption, and, in exactly the same way actually, it showed that there was no demand for it in Putin’s model of the redistribution of raw materials and the whole ephemeral post-Soviet ‘middle class’. Striking against cheese was equivalent to carrying out a strike against the quasi-Western idea of normality and bourgeois values, and a return to the strict Russian archetype: for the Russian it is kolbasa , salami-type sausage, that is symbolically valuable, while cheese is simply urban capriciousness, because you don’t follow a shot of vodka with a piece of cheese. So in this sense cheese underlines the narrow dividing line between Russian tradition and our superficial Westernization.

Here we have to state the obvious, sad though it is. Despite multiple attempts to establish a culture of cheese production in Russia’s vast expanses and poor soils, from Peter the Great through to Stalin’s Head of Food Production, Anastas Mikoyan, and today’s heroic Russian dairy farmers, cheese remains a product that is alien to the Russian soul. Its lifecycle is too long for Russian history and everyday life in the country. Like wine and olive oil, cheese is the product of a stable culture. Roquefort has been made since the eleventh century; Gruyère and Cheshire cheese since the twelfth; Parmesan, Gorgonzola, Taleggio and Pecorino since the fourteenth. But it’s less a question of the length of the tradition than it is the time it takes for the cheese to mature: thirty-six months for Parmesan; five to six years for mature Gouda. For cheese to able to spend such a long time maturing, you need political and social stability, guarantees of the rights of ownership, credit and a steady demand. Cheese is an investment in a reliable future.

In Russia they made tvorog (a kind of cottage cheese), which can be made quickly and which also goes off very quickly. You put the milk out in the evening, drain it the next morning, and eat it the following evening, by which time it’s already beginning to go sour. The Russian peasant had no certainty about the future: tomorrow there could be war, a military call-up, a corvée [14] A day’s unpaid work demanded of a vassal by his overlord.

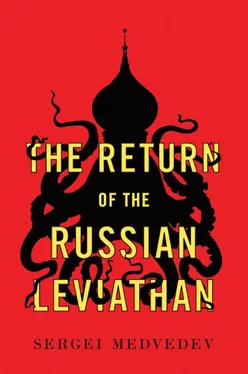

or Bolshevik demands for extra produce. The peasant didn’t manage his own life or his own property; he didn’t have time to make cheese, he just wanted to stay alive. Russian production of both material goods and foodstuffs has always been the victim of the climate and the country’s history, which dictate quick production and use; and also the victim of weak institutions under which there is no right to ownership, nor the possibility for long-term planning and storage. There is just a single Leviathan state, which can never be satisfied and which will gobble up any surplus – and cheese comes about as the result of a surplus of milk.

Читать дальше