Consider a turkey that is fed every day. Every single feeding will firm up the bird’s belief that it is the general rule of life to be fed every day by friendly members of the human race “looking out for its best interests,” as a politician would say. On the afternoon of the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, something unexpected will happen to the turkey. It will incur a revision of belief. *

The rest of this chapter will outline the Black Swan problem in its original form: How can we know the future, given knowledge of the past; or, more generally, how can we figure out properties of the (infinite) unknown based on the (finite) known? Think of the feeding again: What can a turkey learn about what is in store for it tomorrow from the events of yesterday? A lot, perhaps, but certainly a little less than it thinks, and it is just that “little less” that may make all the difference.

The turkey problem can be generalized to any situation where the same hand that feeds you can be the one that wrings your neck . Consider the case of the increasingly integrated German Jews in the 1930s—or my description in Chapter 1 of how the population of Lebanon got lulled into a false sense of security by the appearance of mutual friendliness and tolerance.

Let us go one step further and consider induction’s most worrisome aspect: learning backward. Consider that the turkey’s experience may have, rather than no value, a negative value. It learned from observation, as we are all advised to do (hey, after all, this is what is believed to be the scientific method). Its confidence increased as the number of friendly feedings grew, and it felt increasingly safe even though the slaughter was more and more imminent. Consider that the feeling of safety reached its maximum when the risk was at the highest! But the problem is even more general than that; it strikes at the nature of empirical knowledge itself. Something has worked in the past, until—well, it unexpectedly no longer does, and what we have learned from the past turns out to be at best irrelevant or false, at worst viciously misleading.

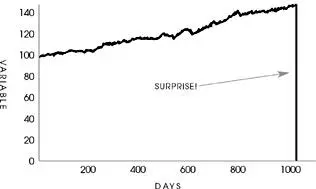

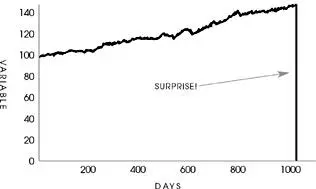

FIGURE 1: ONE THOUSAND AND ONE DAYS OF HISTORY

A turkey before and after Thanksgiving. The history of a process over a thousand days tells you nothing about what is to happen next. This naïve projection of the future from the past can be applied to anything.

Figure 1 provides the prototypical case of the problem of induction as encountered in real life. You observe a hypothetical variable for one thousand days. It could be anything (with a few mild transformations): book sales, blood pressure, crimes, your personal income, a given stock, the interest on a loan, or Sunday attendance at a specific Greek Orthodox church. You subsequently derive solely from past data a few conclusions concerning the properties of the pattern with projections for the next thousand, even five thousand, days. On the one thousand and first day—boom! A big change takes place that is completely unprepared for by the past.

Consider the surprise of the Great War. After the Napoleonic conflicts, the world had experienced a period of peace that would lead any observer to believe in the disappearance of severely destructive conflicts. Yet, surprise! It turned out to be the deadliest conflict, up until then, in the history of mankind.

Note that after the event you start predicting the possibility of other outliers happening locally, that is, in the process you were just surprised by, but not elsewhere . After the stock market crash of 1987 half of America’s traders braced for another one every October—not taking into account that there was no antecedent for the first one. We worry too late—ex post. Mistaking a naïve observation of the past as something definitive or representative of the future is the one and only cause of our inability to understand the Black Swan.

It would appear to a quoting dilettante—i.e., one of those writers and scholars who fill up their texts with phrases from some dead authority—that, as phrased by Hobbes, “from like antecedents flow like consequents.” Those who believe in the unconditional benefits of past experience should consider this pearl of wisdom allegedly voiced by a famous ship’s captain:

But in all my experience, I have never been in any accident… of any sort worth speaking about. I have seen but one vessel in distress in all my years at sea. I never saw a wreck and never have been wrecked nor was I ever in any predicament that threatened to end in disaster of any sort .

E. J. Smith, 1907, Captain, RMS Titanic

Captain Smith’s ship sank in 1912 in what became the most talked-about shipwreck in history. *

Trained to Be Dull

Similarly, think of a bank chairman whose institution makes steady profits over a long time, only to lose everything in a single reversal of fortune. Traditionally, bankers of the lending variety have been pear-shaped, clean-shaven, and dress in possibly the most comforting and boring manner, in dark suits, white shirts, and red ties. Indeed, for their lending business, banks hire dull people and train them to be even more dull. But this is for show. If they look conservative, it is because their loans only go bust on rare, very rare, occasions. There is no way to gauge the effectiveness of their lending activity by observing it over a day, a week, a month, or … even a century! In the summer of 1982, large American banks lost close to all their past earnings (cumulatively), about everything they ever made in the history of American banking—everything. They had been lending to South and Central American countries that all defaulted at the same time—“an event of an exceptional nature.” So it took just one summer to figure out that this was a sucker’s business and that all their earnings came from a very risky game. All that while the bankers led everyone, especially themselves, into believing that they were “conservative.” They are not conservative; just phenomenally skilled at self-deception by burying the possibility of a large, devastating loss under the rug. In fact, the travesty repeated itself a decade later, with the “risk-conscious” large banks once again under financial strain, many of them near-bankrupt, after the real-estate collapse of the early 1990s in which the now defunct savings and loan industry required a taxpayer-funded bailout of more than half a trillion dollars. The Federal Reserve bank protected them at our expense: when “conservative” bankers make profits, they get the benefits; when they are hurt, we pay the costs.

After graduating from Wharton, I initially went to work for Bankers Trust (now defunct). There, the chairman’s office, rapidly forgetting about the story of 1982, broadcast the results of every quarter with an announcement explaining how smart, profitable, conservative (and good looking) they were. It was obvious that their profits were simply cash borrowed from destiny with some random payback time. I have no problem with risk taking, just please, please, do not call yourself conservative and act superior to other businesses who are not as vulnerable to Black Swans.

Another recent event is the almost-instant bankruptcy, in 1998, of a financial investment company (hedge fund) called Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), which used the methods and risk expertise of two “Nobel economists,” who were called “geniuses” but were in fact using phony, bell curve–style mathematics while managing to convince themselves that it was great science and thus turning the entire financial establishment into suckers. One of the largest trading losses ever in history took place in almost the blink of an eye, with no warning signal (more, much more on that in Chapter 17). *

Читать дальше