II . The second type of decision is more complex and entails more openended exposures. You do not just care about frequency or probability, but about the impact as well, or, even more complex, some function of the impact. So there is another layer of uncertainty of impact. An epidemic or a war can be mild or severe. When you invest you do not care how many times you gain or lose, you care about the cumulative, the expectation: how many times you gain or lose times the amount made or lost. There are even more complex decisions (for instance, when one is involved with debt) but I will skip them here.

We also care about which

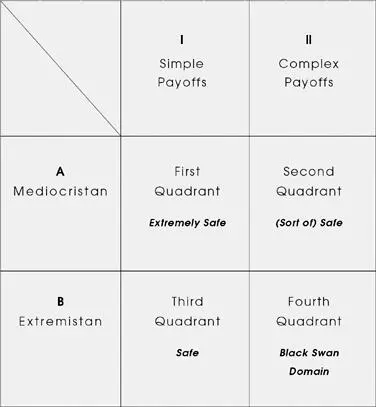

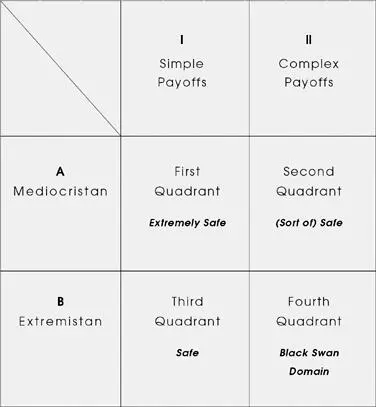

A . Event generators belong to Mediocristan (i.e., it is close to impossible for very large deviations to take place), an a priori assumption.

B . Event generators belong to Extremistan (i.e., very large deviations are possible, or even likely).

Which provides the four quadrants of the map.

THE FOURTH QUADRANT, A MAP

First Quadrant . Simple binary payoffs, in Mediocristan: forecasting is safe, life is easy, models work, everyone should be happy. These situations are, unfortunately, more common in laboratories and games than in real life. We rarely observe these in payoffs in economic decision making. Examples: some medical decisions (concerning one single patient, not a population), casino bets, prediction markets.

TABLE 1: TABLEAU OF DECISIONS BY PAYOFF M0 “True/False” M1 Expectations Medical results for one person (health, not epidemics) Epidemics (number of persons infected) Psychology experiments (yes/no answers) Intellectual and artistic success (defined as book sales, citations, etc.) Life/Death (for a single person, not for n persons) Climate effects (any quantitative metric) Symmetric bets in roulette War damage (number of casualties) Prediction markets Security, terrorism, natural catastrophes (number of victims) General risk management Finance: performance of a nonleveraged investment (say, a retirement account) Insurance (measures of expected losses) Economics (policy) Casinos

Second Quadrant . Complex payoffs in Mediocristan: statistical methods may work satisfactorily, though there are some risks. True, use of Mediocristan models may not be a panacea, owing to preasymptotics, ack of independence, and model error. There clearly are problems here, but these have been addressed extensively in the literature, particularly by David Freedman.

Third Quadrant . Simple payoffs in Extremistan: there is little harm in being wrong, because the possibility of extreme events does not impact the payoffs. Don’t worry too much about Black Swans.

Fourth Quadrant, the Black Swan Domain . Complex payoffs in Extremistan: that is where the problem resides; opportunities are present too. We need to avoid prediction of remote payoffs, though not necessarily ordinary ones. Payoffs from remote parts of the distribution are more difficult to predict than those from closer parts. *

Actually, the Fourth Quadrant has two parts: exposures to positive or negative Black Swans. I will focus here on the negative one (exploiting the positive one is too obvious, and has been discussed in the story of Apelles the painter, in Chapter 13).

TABLE 2: THE FOUR QUADRANTS

The recommendation is to move from the Fourth Quadrant into the third one. It is not possible to change the distribution; it is possible to change the exposure, as will be discussed in the next section.

What I can rapidly say about the Fourth Quadrant is that all the skepticism associated with the Black Swan problem should be focused there. A general principle is that, while in the first three quadrants you can use the best model or theory you can find, and rely on it, doing so is dangerous in the Fourth Quadrant: no theory or model should be better than just any theory or model.

In other words, the Fourth Quadrant is where the difference between absence of evidence and evidence of absence becomes acute .

Next let us see how we can exit the Fourth Quadrant or mitigate its effects.

* This section should be skipped by those who are not involved in social science, business, or, something even worse, public policy. Section VII will be less mundane.

* David left me with a second surprise gift, the best gift anyone gave me during my deserto: he wrote, in a posthumous paper, that “efforts by statisticians to refute Taleb proved unconvincing,” a single sentence which turned the tide and canceled out hundreds of pages of mostly ad hominem attacks, as it alerted the reader that there was no refutation, that the criticisms had no substance. All you need is a single sentence like that to put the message back in place.

* This is a true philosophical a priori since when you assume events belong to Extremistan (because of the lack of structure to the randomness), no additional empirical observations can possibly change your mind, since the property of Extremistan is to hide the possibility of Black Swan events—what I called earlier the masquerade problem.

VII

WHAT TO DO WITH THE FOURTH QUADRANT

NOT USING THE WRONG MAP: THE NOTION OF IATROGENICS

So for now I can produce phronetic rules (in the Aristotelian sense of phronesis , decision-making wisdom). Perhaps the story of my life lies in the following dilemma. To paraphrase Danny Kahneman, for psychological comfort some people would rather use a map of the Pyrénées while lost in the Alps than use nothing at all. They do not do so explicitly, but they actually do worse than that while dealing with the future and using risk measures. They would prefer a defective forecast to nothing. So providing a sucker with a probabilistic measure does a wonderful job of making him take more risks. I was planning to do a test with Dan Goldstein (as part of our general research programs to understand the intuitions of humans in Extremistan). Danny (he is great to walk with, but he does not do aimless strolling, “flâner”) insisted that doing our own experiments was not necessary. There is plenty of research on anchoring that proves the toxicity of giving someone a wrong numerical estimate of risk. Numerous experiments provide evidence that professionals are significantly influenced by numbers that they know to be irrelevant to their decision, like writing down the last four digits of one’s social security number before making a numerical estimate of potential market moves. German judges, very respectable people, who rolled dice before sentencing issued sentences 50 percent longer when the dice showed a high number, without being conscious of it.

Negative Advice

Simply, don’t get yourself into the Fourth Quadrant, the Black Swan Domain. But it is hard to heed this sound advice.

Psychologists distinguish between acts of commission (what we do) and acts of omission. Although these are economically equivalent for the bottom line (a dollar not lost is a dollar earned), they are not treated equally in our minds. However, as I said, recommendations of the style “Do not do” are more robust empirically. How do you live long? By avoiding death. Yet people do not realize that success consists mainly in avoiding losses, not in trying to derive profits.

Читать дальше