At the age of thirty-three, Darwin’s period of great physical activity was over. Darwin logs continual, nagging complaints in his diaries from 1839 until his death in 1882 that indicate a persistent and not readily diagnosed problem:

the smallest exertion is most irksome… periodic vomiting… I was almost quite broken down, head swimmy, hands trembling and never a week without violent vomiting… very weak… only able to tolerate short walks… headaches… fatigued… oppressed.. .flatulence… prolonged spells of daily vomiting of “acid & slime,” fright… sinking sensation… trembling… shivering… and fatigue. (Darwin, in Goldstein 1989)

These symptoms waxed and waned throughout Darwin’s life and greatly curtailed his professional activities, travels, and social life. In 1882 Darwin developed myocardial degeneration which progressed to angina pectoris; he died that year.

Some facts, however, work against the idea that Darwin died from Chagas’ disease. Darwin’s illness in many ways is not characteristic of Chagas’ disease. Darwin never mentioned the first signs of the acute phase, development of a chagoma, a rash consisting of tiny red spots, fever, and spleen and heart problems. However, the majority of afflicted adults (60 to 70 percent) do not suffer symptoms of the acute phase. Ignorance of this factor remains a problem because many infected individuals with chronic Chagas’ disease claim they are not infected since they did not suffer symptoms of the acute phase. Chagas’ disease is frequently asymptomatic until years after the initial infection. The observation that Darwin reported no high fever is not sufficient in itself to rule out Chagas’ disease.

Exhibiting limited knowledge, Browne (1995:280) refers to Chagas’ disease as a South American sleeping sickness, with the implication that because Darwin did not suffer a fever typical of African sleeping sickness he did not have Chagas’ disease. American trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ disease) and African trypanosomiasis (African sleeping sickness) are both caused by trypanosome parasites: one by Salivaria, which lives in the saliva of its vector insect, and the other by Sterecoria, which lives in the feces of its vector insect. The difference between these parasites is that African trypanosomes remain in the blood and cause recurring fevers that exhaust the immune system; in contrast, American trypanosomes enter the neuron cells and frequently do not trigger immediate action of the immune system. American trypanosomes also reenter the blood.

Although Darwin’s symptoms did not indicate heart disease until he was seventy-one, a relatively long life for the nineteenth century, he could have suffered subtler degrees of myocardial dysfunction, associated with T. cruzi, causing many of the complaints listed in his correspondence (see Adler 1959; Medawar 1964; Goldstein 1989). This debate has brought attention to Chagas’ disease, sometimes referred to as Darwin’s disease, and its diffuse nature and complex symptoms. Some hope that Darwin’s body will be exhumed and its tissues examined for T. cruzi.

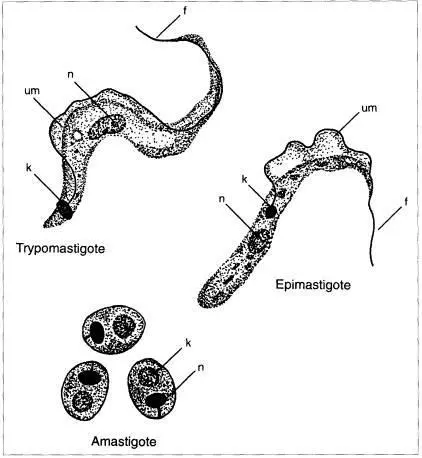

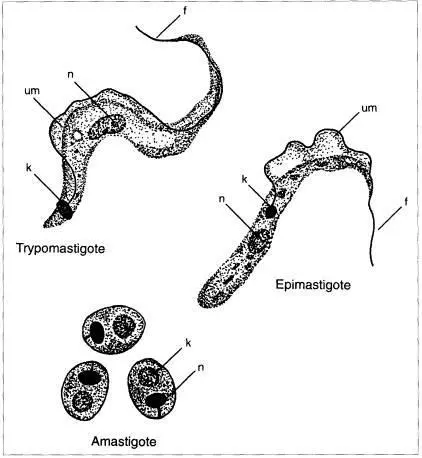

Darwin studied evolution from simple to complex creatures; Chagas studied how simple organisms destroy complex organisms. Chagas examined barbeiros which he collected. In sunlight he dried them and dissected their intestines, eventually finding some flagellates inside the lower intestines (see Figure 5).

Flagellates are protozoa, unicellular creatures that usually reproduce asexually and have flagella, or hairlike whips, propelling or pulling them. There are about 66,000 documented species of protozoa, with about half being represented in fossils; of the living species, about 10,000 are parasitic (Katz, Despommier, and Gwadz 1989). Unlike most of the helminths (worms), parasitic protozoa reproduce within the host to produce hundreds of thousands of individuals within a few days. They can pose major problems to human existence, causing malaria, giardia, vaginitis, amoebic dysentery, Toxoplasma gondii, African sleeping sickness, leishmaniasis, and pneumonia, among other ailments.

Chagas observed the newly found flagellates with the microscope, making fixed and stained microscope preparations, hoping to recognize the species or be able to characterize it as a new one. He observed that the parasite possessed a different morphological aspect than Trypanosoma minasensi, already recognized in Brazil, although it was a trypanosome, characterized by the undulating membrane, the large size of its basal body, or centriole, an organelle for cell division, and its undulating flagellum.

Chagas correctly identified the flagellated protozoan as a member of the family of trypanosomidae, but he believed it to be a previously undescribed genus and species. He named it Schizotrypanum cruzi: “ in tribute to the master, Oswaldo Cruz, to whom I owe everything in my scientific career, and who guided me in these studies toward wide horizons, an adviser at any moment, a spirit of light and kindness, always quick in giving me the benefits of his knowledge and protecting me in the greatness of his affection” (in Kean 1977). (Oswaldo Cruz would also be memorialized by the founding of the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, a world-renowned research center of tropical diseases in Brazil.) Schizotrypanum cruzi was later reclassified as Trypanosoma cruzi because it fits better into the genus of trypanosomes (see Chagas Filho 1993:85).

Figure 5.

Forms of T. cruzi: n = nucleus, k = kinetoplast, um = undulating membrane, f= flagellum. (See Appendix 1.)

Once Chagas had found T. cruzi, he still wasn’t sure that this parasite inhabited humans or other mammals, or that it caused the “strange disease.” Countless parasites are beneficial to humans; it was even possible that T. cruzi curtailed the reproduction of vinchucas. Hypothetically, Carlos Chagas reasoned that his Schizotrypanum cruzi was either natural to barbeiros, creating no sickness, or that the flagellates found in the gut of barbeiros represented one stage of a transforming parasite that passed over to mammals and caused the reported symptoms in Lassance. Consequently, he examined tissues of animals and humans who had died from this “strange disease” to see if they were infected with T. cruzi.

Another clue for Chagas was that Trypanosoma cruzi resembles Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, a flagellate protozoan that lives in the blood of cattle and humans, causing African sleeping sickness. Uninfected tsetse flies bite cattle and humans infected with T. b. gambiense, which are frequently asleep during the middle of the day (hence the origin of the disease’s name) and ingest the parasite. The parasite transforms into a metacyclic trypanosome in the saliva of the fly; from there it moves on to another host. Using plasmodia and trypanosoma parasites as models, Chagas suspected that T. cruzi had a similar cycle between barbeiros and mammals, causing yet another disease within them. He suspected that because T. cruziwas found in the rear gut of barbeiros, it was passed through the insect’s fecal matter to humans after the insect bit and then defecated near the wound. The parasite then entered through the bite wound.

In April 1908 Chagas spent the night in a house where he found a sickly cat, which he examined, finding T. cruzi. Two weeks later, he again visited the same house to treat a three-year-old child, Rita, feverishly ill. He found a large swarm of insects biting the inhabitants, including Rita, who had been healthy during his earlier visit. After he examined her blood, he found “the existence of flagellates,” as Chagas (1922) described it, “in good number and the fixing and staining of blood films made it possible to characterize the parasite’s morphology and to identify it with Trypanosoma cruzi.”

Читать дальше