Rita had a fever of 40°C (105°F) for two weeks. Her spleen and liver were enlarged and her lymph nodes were swollen. Most noticeable to Chagas was a generalized infiltration, more pronounced in the face, and which did not show the characteristics of renal edema but rather of myxedema. Carlos Chagas (1911) found this last symptom to be one of the most characteristic forms of the acute stage of the disease; it revealed some functional alteration of the thyroid gland, perhaps affected by the pathogenic action of the parasite.

Three days later, Rita died from parasitemia caused by T. cruzi. Today, some ninety years after Rita’s death, seven children die each day from the acute phase of Chagas’ disease in Bolivia (Ault et al. 1992:9). Carlos Chagas also treated another patient in 1908, a woman named Bernice, who died in 1989 still harboring the parasite but with no evidence of pathology (Carlos Chagas Filho 1993).

Figure 6.

Carlos Chagas lecturing to doctors about Chagas’ disease. (Photo from Renato Clark Bacellar, Brazil’s Contribution to Tropical Medicine and Malaria, Rio de Janeiro, 1963)

The pathology of Chagas’ disease varies from a mild and inapparent infection as was found in Bernice, who outlived Carlos Chagas by twenty-seven years, to Rita, the three-year-old girl who died from a virulent acute infection. Because its pathology varies so widely, the diagnosis of Chagas’ disease from symptoms is difficult.

Animal studies were needed by Chagas to claim that Trypanosoma cruzi was the pathogenetic agent causing the fever and heart diseases. Even though the parasite had been found in insects and in a human, evidence was still lacking that it created the observed symptoms. Chagas sent some barbeiros infected with Trypanosoma cruzi to Cruz in Rio. Cruz injected the bugs’ intestinal contents into three uninfected callithrix monkeys. When the monkeys started dying some days later, Cruz cabled Chagas to come to Rio to see the results.

The journey from Lassance was a grueling twenty-four-hour trip, with two train changes and long waits. Chagas and Cruz knew that this discovery would place them, the Institute Oswaldo Cruz, and Brazil in the forefront of tropical medicine throughout the world. Cruz met Chagas at the railroad station and took him directly to the laboratory, where the mammalian pathogenicity of the flagellate was confirmed.

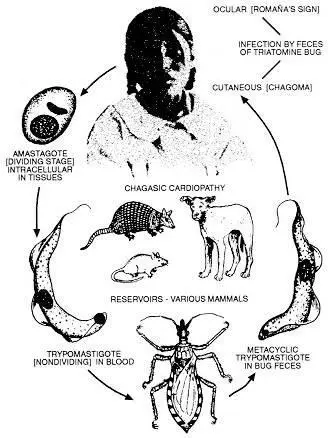

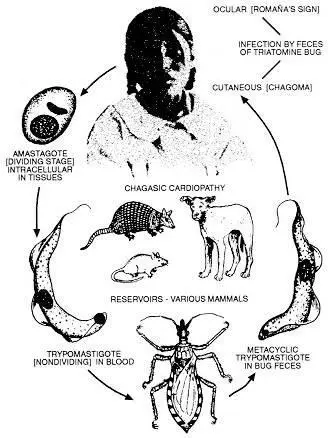

Figure 7.

Parasitic cycle of T. cruzi. (See Appendix 1.)

Carlos Chagas and Oswaldo Cruz later proved that T. cruzi passes from Triatoma infestans through fecal matter when these bugs defecate near the bite site. T. cruzi then enters through the skin or bite site into the human’s blood and nerve cells. The parasitic cycle of this disease included T. cruzias the pathogenic agent, which was transmitted by triatomine insects through their fecal matter to mammalian hosts (animals and humans). People become infected with T. cruzi by indirect contamination through the fecal matter of vinchucas and by direct transmission through blood or cells at birth and in blood transfusions and organ transplants. Vinchucas are directly infected with T. cruzi through their ingestion of the blood of infected animals and humans. T. cruzi transforms and reproduces in the vector and the host, both being necessary for its survival (see Figure 7).

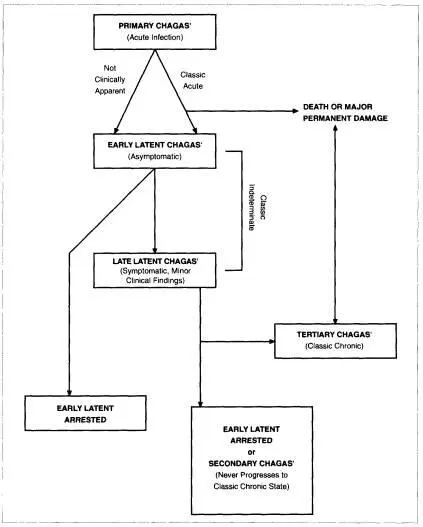

Progression of Chagas’ Disease

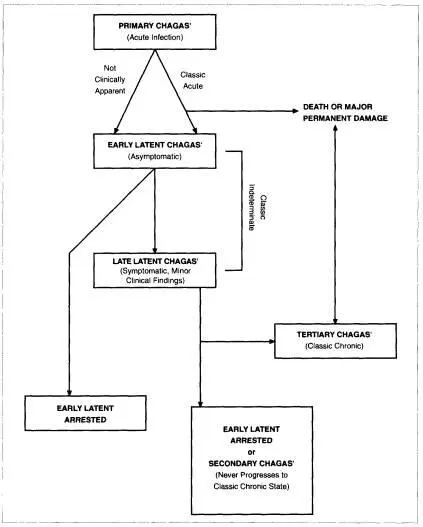

Carlos Chagas discovered the symptoms and progression of Chagas’ disease. Figure 8 illustrates how Chagas’ disease progresses, which is a complex and in part unresolved issue. Primary Chagas’ disease refers to the acute infection stage, which may not be clinically apparent, with about 25 percent of infected patients indicating it (see Appendix 9). If apparent, it is characterized by inflammation that may include fever, general malaise, swelling and soreness of the lymph nodes and spleen, and by Signo de Romaña, severe swelling around the eye. People die or suffer permanent damage during the acute phase; those who survive have classic chronic or tertiary Chagas’ disease.

Infected victims pass into early latent Chagas’, which is asymptomatic. Latent Chagas’ offers several possibilities: 1) the infection is arrested at this stage, 2) it develops later to late latent Chagas’ with minor clinical findings, or 3) it develops into classic chronic (tertiary) Chagas’ disease. Those with minor clinical findings progress to either early latent arrested (secondary) Chagas’ or classic chronic (tertiary) Chagas’.

A certain number of patients live out their lives in the early latent arrested phase, with no noticeable symptoms, except perhaps fatigue. As mentioned, one acute patient of Carlos Chagas in 1909, Bernice, lived past the age of seventy and was checked annually, with no symptoms of the disease ever being manifested (Lewinsohn 1979:519). However, in many instances, the disease culminates with classic chronic symptoms of tertiary Chagas’heart disease and enlarged colon and esophaguswhich if untreated result in death. There is no known cure for the chronic phase.

Chagas’ disease is closely related to the immune system. Its progression varies greatly with the immunocompetence of each individual. Bolivians suffer so greatly from it in part because many are malnourished and infected with other diseases (see Appendix II).

At the Brazilian National Academy of Medicine’s session on April 22, 1909, Oswaldo Cruz read Chagas’ work entitled “A New Human Trypanosomiasis.” Cruz referred to the new disease as American trypanosomiasis to distinguish it from African trypanosomiasis, but American trypanosomiasis was soon known as Chagas’ disease (Kean 1977). Shortly after the reading of the paper, Cruz and a group of distinguished physicians traveled to Lassance to visit Chagas at work. Miguel Couto described the visit:

Carlos Chagas was waiting for us with his museum of laboratory items. Examination between cover-glass and slide revealed the raritiesseveral dozen patients of all ages, some idiots, others paralytics, others heart cases, thyroids, myxedemics and asthenics. Microscopes were scattered all over the tables showing trypanosomes in movement, or pathological anatomic lesions. In the cases were animals experimentally infected and jars full of triatomines in all stages of development. Every item of this demonstration was carefully examined by us. The doctors gathered there, undisputable authorities in their fields… had nothing to deny or add to the analysis of the symptoms or their interpretations… On that day it was up to me to give a name to those traditional diseases of the Minas backlands, which were now unified as one disease with cause and development clearly established. To name it after only one of its symptoms would be to limit its description, and to name it for all its symptoms would be impossible… And so, at dinner, while toasting Carlos Chagas, I… chosen because of my age, standing with Oswaldo Cruz on my right and surrounded by the men most representative of Brazilian medicine of that era, with gravity equal to a liturgical act in our religion, such as a baptism, gave the name of Chagas’ Disease to that illness…in the name of the entire delegation (Couto, in Kean 1977).

Figure 8.

Progression of Chagas’ disease. (From Jared Goldstein, “Darwin, Chagas’, Mind, and Body,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 32, no. 4 ([1989]:595.)

Carlos Chagas died in 1933 of angina pectoris as he was looking through a microscope into the universe of parasites. A year before his death, he optimistically spoke to a class of graduating physicians: “Gentlemen, the practical applications of hygiene and tropical medicine have destroyed the prejudice of a fatal climate; the scientific methods are prevailing against the sickness of the tropics” (Kean 1977). On a less optimistic occasion, he remarked, “This is a beautiful land, with its tremendous variety of vegetation. Nature made animal and vegetable life stronger and thus created conditions which bring sickness and death to the men who live here” (Chagas Filho 1993).

Читать дальше