The experience of being fěted and employed as an exotic magician, combined with the sense of isolation which has always accompanied Picasso’s awareness of himself as a prodigy, re-awoke the vertical invader. Perhaps the sense of loss he must have felt about his Cubist friends contributed to the awakening. Aware of being exiled from the one period in which he had been accepted by others as an equal, in which he felt at home, he now became more sharply conscious of his other exile from Spain.

49 Picasso as a matador. 1924

A frontal attack like Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was out of the question; Picasso was still enjoying his success. All that the vertical invader claimed was recognition of his origins. He had conquered but he needed to fly his own standard.

It was at this time that Picasso first began to caricature European art, the art of the museums. At first, and very gently, he caricatured Ingres.

50 Ingres. Drawing. 1828

51 Picasso. Madame Wildenstein. 1918

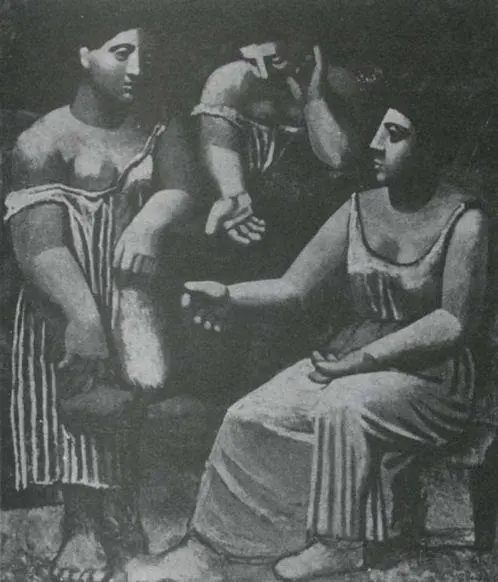

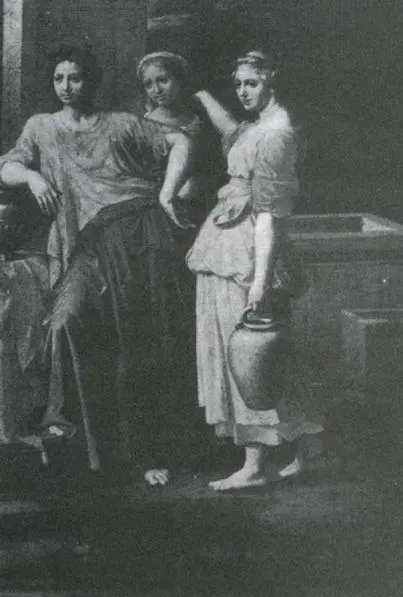

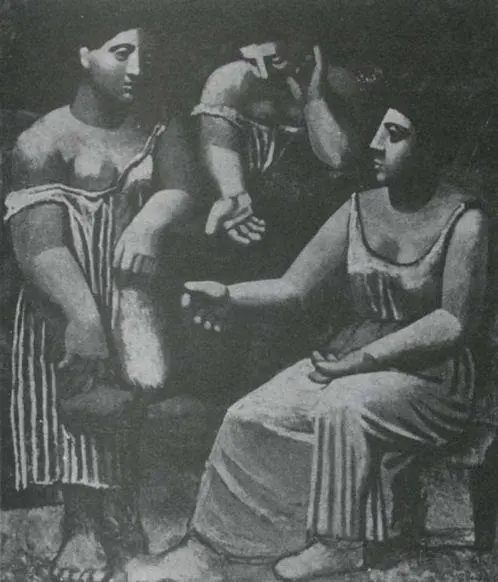

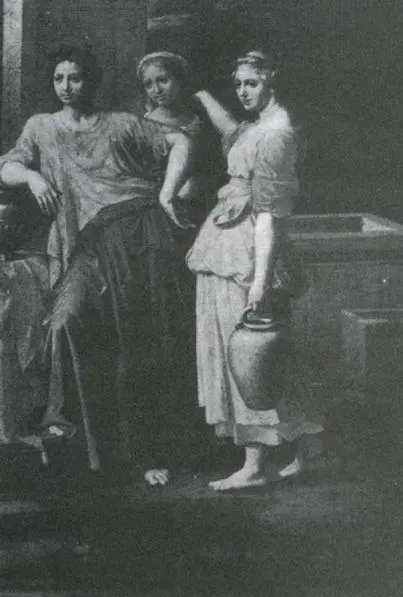

Later and more obviously he caricatured the classic ideal, as found in Greek sculpture and in Poussin.

52 Picasso. Women at the Fountain. 1921

53 Poussin. Eliezer and Rebecca (detail). 1648

The word caricature may give the wrong impression. Perhaps these works of Picasso are more like a performance by an impersonator of genius. The performance is too skilful to be considered a mere joke. Yet there is certainly an element of mockery.

For the vertical invader these impersonations or caricatures serve two purposes. First they prove that he can do what the masters have done: that he — who has no terms of his own — can challenge them all on their own terms. Secondly they suggest that, if this is possible, the value and honour officially given to cultural traditions may be exaggerated. If a commoner can perform as a king, where is the justification for royalty? They are not made out of disrespect for the artists concerned, but out of contempt for the idea of a cultural hierarchy.

Perhaps I should add that, although such works prove Picasso’s comparable skill, they are not as satisfying or profound as the originals, because there is a self-conscious division between their form and content. The way in which they are painted or drawn does not arise directly out of what Picasso has to say about his subject , but instead out of what Picasso has to say about art history. It is the limitation of pastiche: a pastiche always has two heads. Picasso gives Madame Wildenstein the mask of an Ingres; he could have given her the mask of a Lautrec, but it would have been socially undesirable. Ingres draws Madame Delorme as he sees her. It is true that he also idealizes and formalizes her, but these formalizations have become part of his way of seeing, they are the mode of his talent’s obsession.

There was a second way in which the vertical invader claimed recognition. From the early twenties onwards Picasso began to make oracular statements about his art. Finding himself treated as a ‘magician’ — in the fashionable sense of the word — he began to discover within himself a more serious magical basis for his work.

The essence of magic is the primitive belief that the will can control the latent forces and spirits residing in all objects and all nature. The power to bewitch and the state of being possessed are superstitious legacies from this early belief. The Spanish duende is not far removed from magic. Generally speaking, some belief in magic persisted up to the stage of social development of the clan — and the clan, if not a continuing reality, was at least a memory in Spain.

Frazer in The Golden Bough defines magic as mistaking an ideal connexion for a real one.

Men mistook the order of their ideas for the order of nature, and hence imagined that the control which they have, or seem to have, over their thoughts, permitted them to exercise a corresponding control over things.

Magic is an illusion. But its relevance should not be underestimated in the modern world. 13To some extent all art derives its energy from the magical impulse — the impulse to master the world by means of words, rhythm, images, and signs. Magic first led man to the beginnings of science. And now, modern science confirms, if not the practice, at least some of the concepts of magic. The concept of ‘action at a distance’, with which Faraday struggled and from which he created the concept of the field of force, was fundamental to magic. So also was the conviction that reality was indivisible. Magic offered a blueprint of a unified world in which division — and therefore alienation — was impossible. This blueprint, which had no more substance than a dream, has now become a scientific aim. Magic may be an illusion but it is less profoundly so than utilitarianism.

It is hard to say how conscious Picasso is of talking about his art in terms of magic. What he says is sincere; it describes what he feels when working. At the same time it emphasizes the difference between himself and those who buy his pictures and lionize him. He establishes his right to ignore a certain kind of reasoning. Instead he establishes a logic of his own through which he can express his sense of the mysterious power which he has brought with him from childhood and from the past.

I deal with painting as I deal with things, I paint a window just as I look out of a window. If an open window looks wrong in a picture, I draw the curtain and shut it, just as I would in my own room.

This is a perfect example of ‘mistaking’ an ideal connexion for a real one. Or again, expressed more abstractly: ‘I don’t work after nature, but before nature and with her.’ This is a definition of magic.

The power which Picasso possesses means that he must be granted a special licence:

It is my misfortune — and probably my delight — to use things as my passions tell me. What a miserable fate for a painter who adores blondes to have to stop himself putting them into a picture because they don’t go with the basket of fruit! How awful for a painter who loathes apples to have to use them all the time because they go so well with the cloth. I put all the things I like into my pictures. The things — so much the worse for them: they just have to put up with it.

On one level, Picasso is claiming here his right to adore blondes — in the flesh. Baskets of fruit notwithstanding, no painter has ever had to stop himself painting blondes! But on another level there is the implication that his passions, his will, can control ‘things’ — even against their wishes, and that by means of painting a ‘thing’, he possesses it.

He can be possessed himself, but not in the sense in which the word is understood in the Rue de la Boëtie, a fashionable street of antique-dealers and objets d’art , into which he moved in 1918.

The artist is a receptacle for emotions that come from all over the place: from the sky, from the earth, from a scrap of paper, from a passing shape, from a spider’s web. That is why we must not discriminate between things. Where things are concerned there are no class distinctions.

Читать дальше