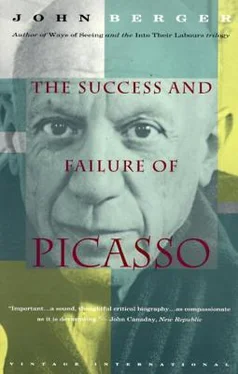

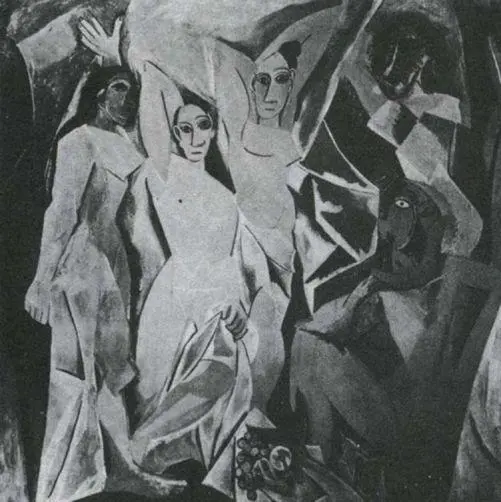

I emphasize the violent and iconoclastic aspect of this painting because usually it is enshrined as the great formal exercise which was the starting point of Cubism. It was the starting point of Cubism, in so far as it prompted Braque to begin painting at the end of the year his own far more formal answer to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon , and, soon after that, Picasso and Braque worked ‘rather like mountaineers roped together’ (to quote Braque’s phrase). Yet if he had been left to himself, this picture would never have led Picasso to Cubism or to any way of painting remotely resembling it. This is a vertical invader’s ‘propaganda by deed’. It has nothing to do with that twentieth-century vision of the future which was the essence of Cubism.

Yet it did mark the beginning of the great period of exception in Picasso’s life. Nobody can know exactly how the change began inside Picasso. We can only note the results. Les Demoiselles d’ Avignon , unlike any previous painting by Picasso, offers no evidence of skill . On the contrary, it is clumsy, overworked, unfinished. It is as though his fury in painting it was so great that it destroyed his gifts.

Such an interpretation also fits the other outstanding fact. Up to 1907 Picasso had followed his own apparently lonely road in painting. He did not influence his contemporaries in Paris and he appeared not to be influenced by them. After Les Demoiselles d’Avignon he became part of a group. Apollinaire and his writer friends told him what he and they were searching for. He worked so closely with Braque that sometimes their pictures are barely distinguishable. Later he became a leader for Léger, Juan Gris, Marcoussis and others. It is as though with the disappearance of his prodigious skill Picasso was no longer isolated, no longer bound to his past, but open to the free interchange of ideas.

Apollinaire, who was extraordinarily perceptive about the spirit of people and of his time (far more so than about painting itself), noticed the change as it occurred. A few years after, in 1912, he wrote about it:

There are poets to whom a muse dictates their works, there are artists whose hand is guided by an unknown being who uses them like an instrument. There is no such thing for them as fatigue for they do not work, although they can produce a great deal at any time, on any day, in any country, in all seasons; they are not men but poetic or artistic instruments. Their reason is powerless against themselves, they do not have to struggle and their works show no trace of struggle. They are not divine, they can do without themselves, they are, as it were, an extension of nature. Their works by-pass the intelligence. They can be moving although the harmonies they strike are never humanized. And then there are other poets, other artists who wrestle. They struggle towards nature but have no immediate closeness to nature; they have to draw everything out of themselves, and no demon, no muse inspires them. They are alone and nothing gets expressed except what they themselves have stammered, stammered so often that sometimes after much effort and many attempts they are able to formulate what they wanted to formulate. Men created in the image of God, they will rest one day to admire what they have made. But the weariness! the imperfections! the labour!

Picasso was an artist like the former. There has never been a spectacle so fantastic as the metamorphosis he underwent in becoming an artist like the latter. 12

What Apollinaire, with all his marvellous perception, could not realize is how much he and his friends and Braque had contributed to Picasso’s metamorphosis. And he could not realize this because he did not then know that later, when the group no longer existed and Picasso was left to himself again, he would be transformed back into the first type of artist.

By painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon Picasso provoked Cubism. It was the spontaneous and, as always, primitive insurrection out of which, for good historical reasons the revolution of Cubism developed. This surely becomes clear if one simply looks at seven relevant paintings in chronological sequence.

37 Cézanne. Les Grandes Baigneuses. 1898–1906

38 Picasso. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. 1907

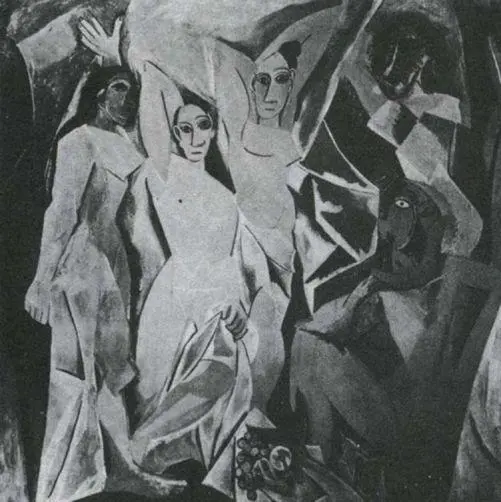

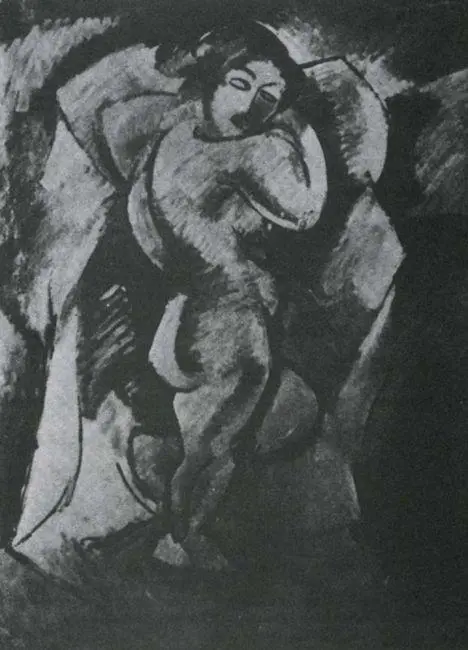

39 Braque. Nude. 1907-8

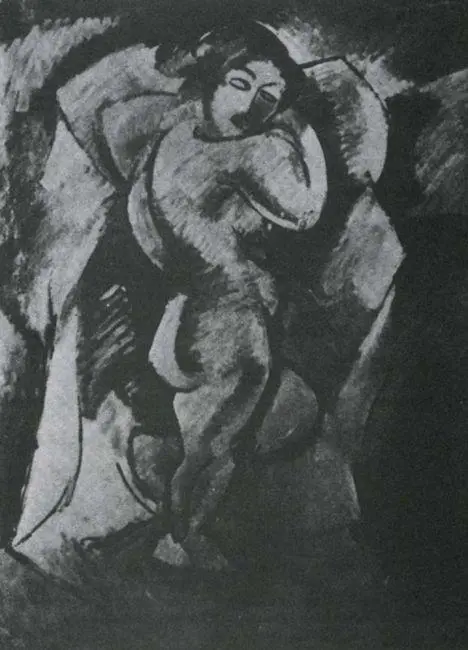

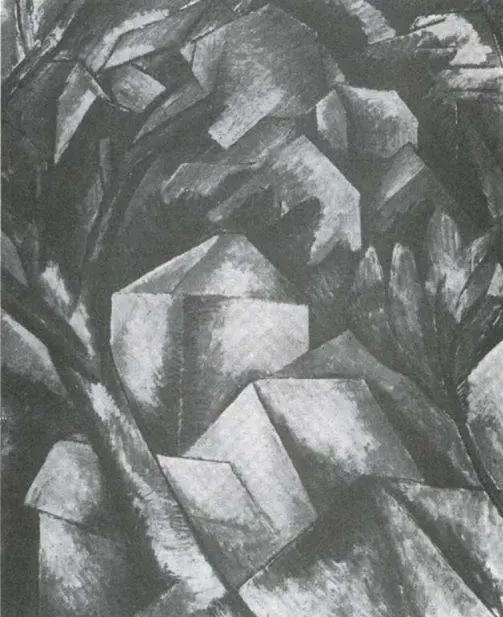

40 Picasso. Landscape with Bridge. 1908

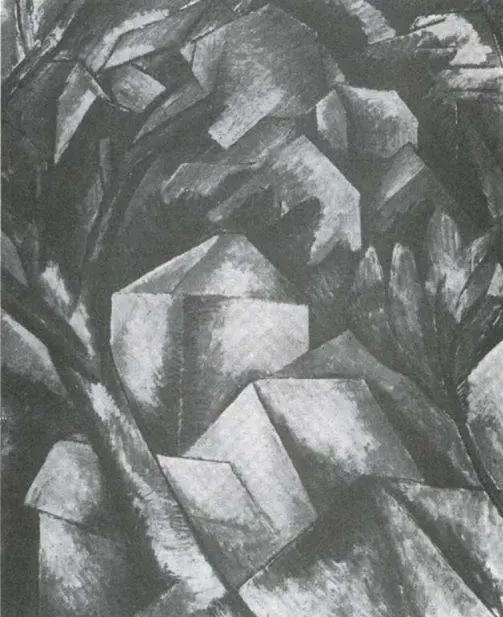

41 Braque. Houses at Estaque. 1908

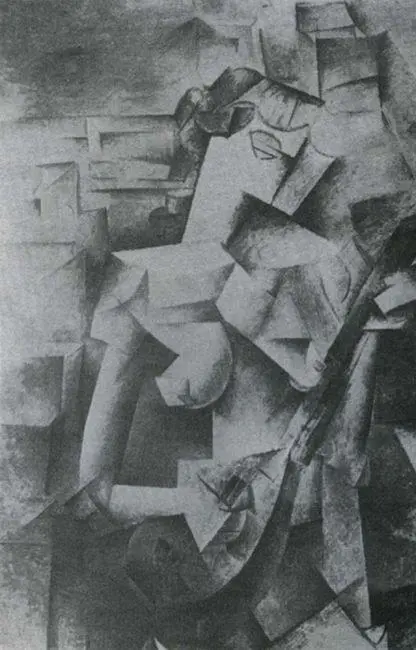

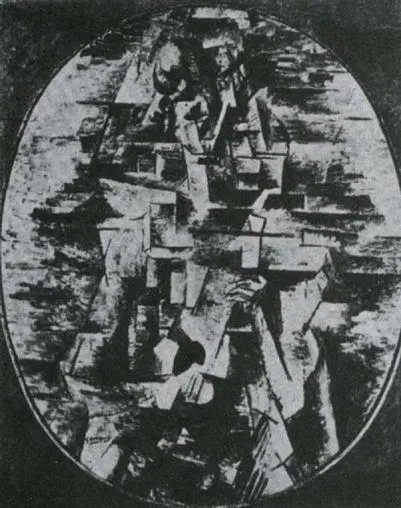

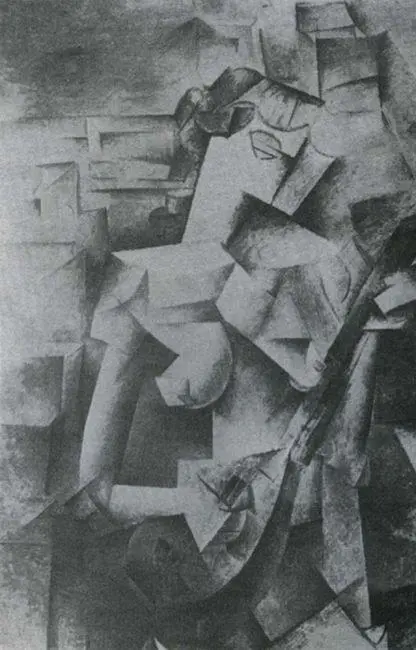

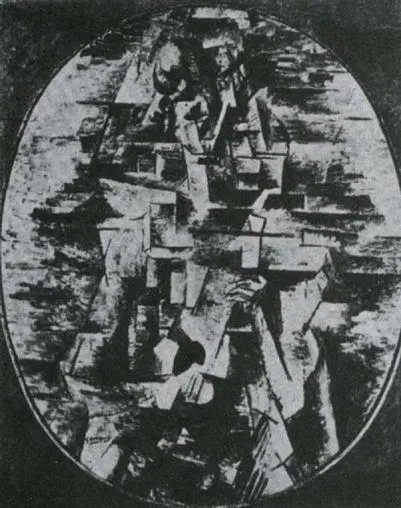

42 Picasso. Girl with a Mandolin. 1910

43 Braque. Girl with a Mandolin. 1910

After Les Demoiselles Picasso became caught up in what he had provoked. He became part of a group. That is not just to say that he had his own circle of friends — for this he had had before and would have afterwards. He became part of a group who, although they did not formulate a programme, were all working in the same direction. This is the only period in Picasso’s whole life when his work to some extent resembles that of other contemporary painters. It is also the one period of his life when his work (despite his own denial of this) reveals an absolutely consistent line of development: from Landscape with a Bridge in 1908 to, say, The Violin of 1913. It was a period of great excitements, but also a period of inner certainty and security. It was, I believe, the only time when Picasso felt entirely at home. It is from that period, as much as from Spain, that he has since been exiled.

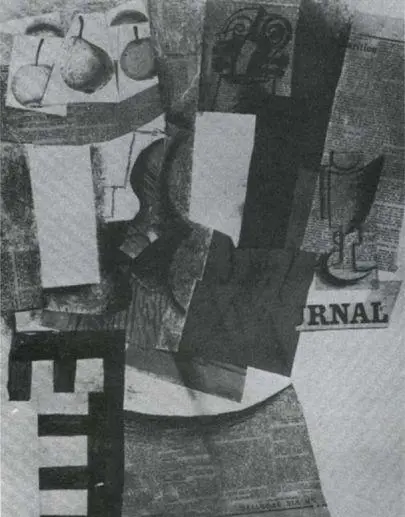

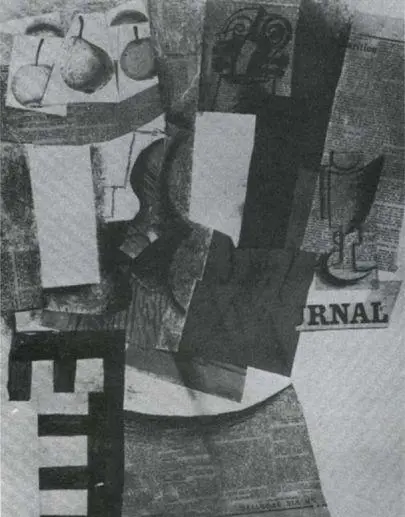

44 Picasso. The Violin. 1913

Within the group (although group is a word that is already a little too formal), within the companionship established, Picasso’s energy and extremism were still outstanding. It was probably he who mostly pushed the arguments and logic to their full pictorial conclusions. (It was he who first thought of sticking extraneous material on to a canvas.) But it was probably his friends who sensed the pressure of what I have called the historical convergence which made Cubism possible. It was they, rather than he, who belonged to the modern world, and so were committed to it. He was committed to his work with them.

In 1914 the group dispersed. Braque, Derain, Léger, Apollinaire went to fight. Kahnweiler, who was Picasso’s dealer, had to flee the country because he was German. Equivalent changes affected millions of people’s lives.

Picasso was unconcerned about the war. It was not his war — another example of how tenuously he belonged to the life around him. Yet he suffered because he was left alone, and his loneliness was increased in 1915 by the tragic death of his young mistress. Under the pressure of this loneliness, he reverted to type. He re-became a vertical invader from the past. But before we examine the full consequences of this, I would like to show by example how, after 1914, the whole relationship between art and reality shifted.

Читать дальше