This is not of course the only logic of a European city. Picasso’s view is one-sided, and this helps to explain the sentimentality of much of his work at this time — such exaggerated hopelessness borders on self-pity. (It is also why, much later, paintings of this period became so popular with the rich. The rich like to think only of the lonely poor: it makes their own loneliness seem less abnormal: and it makes the spectre of the organized, collective poor seem less possible.)

Yet Picasso’s attitude is understandable enough. His politics were very simple. It was among the outcasts, the Lumpenproletariat , that he lived. Their misery was of a kind he had never before imagined. Probably, he was also suffering from venereal disease and was obsessed by it. In many of his pictures at this time he dealt with the theme of blindness. Critics point out that he must have seen many blind beggars in Spain, but I believe the significance of the subject was deeper and more personal: Picasso feared blindness as a result of his disease. He imagined this disease destroying the very centre of him, and this subjective vision corresponded with the real examples of socially induced self-destruction which he saw all around him.

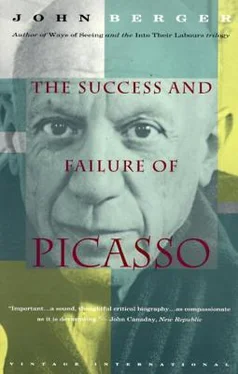

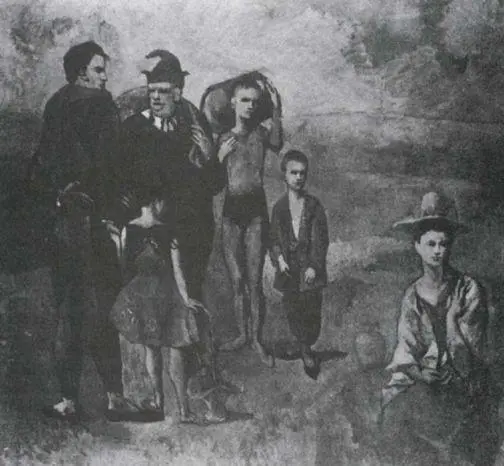

Quite quickly — and it may have been connected with an improvement in his health — Picasso became more defiant. He still painted outcasts and still identified himself with them, but they were no longer hopeless victims. They now had skills and a tradition of their own. They became acrobats or clowns and their way of life was nomadic and independent.

20 Picasso. Clown with a Glass (self-portrait). 1905

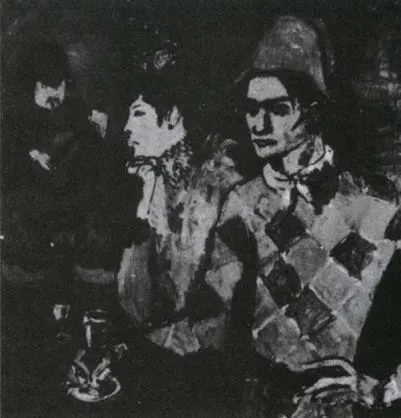

21 Picasso. Family of Saltimbanques. 1905

It becomes highly questionable whether these men and women would ever agree to become members of modern European society. They may be underfed and scantily dressed, but they have kept their distance and self-respect, and the grace of their skills is a token of a purity of spirit unattainable in a modern city. They are primitives in the sense that they are nearer to nature. They may be sad, but they know nothing of legalized suffering.

As if to emphasize this point of their nearness to nature, of their familiarity with natural as opposed to man-made law, Picasso often includes animals in these paintings, but animals with whom the figures have a special understanding. A boy leads a horse. Others ride horses bare-back. A dog nuzzles against a leg. A goat follows a girl. An ape sits beside a woman like a brother to the child on her lap.

22 Picasso. Acrobat’s Family with Ape. 1905

Perhaps I should make it clear that I am not now concerned with judging these pictures — though personally I find them over-nostalgic and mannered. Nor need we be concerned with the stylistic problems which most writers about Picasso set themselves. Why during the Blue Period did Picasso paint in blue? And why did he paint in pink in 1906? The answers may be interesting, but there is a grave danger of not seeing the wood for the trees.

If we are concerned with the spirit of Picasso which appears to dominate all else, then the following is what is essential for our purpose: Picasso recognized that he had to come to Paris because he knew that he had no professional future in Spain; in Paris he came face to face with the misery of a modern European city — a misery which combines brute suffering with delirium; he reacted against this by idealizing simpler, more primitive ways of life.

So far, it might seem that his coming to Paris was of doubtful value. Might it not have been more logical to reject the whole idea of being a professional painter and leave Europe, as Gauguin had done fifteen years earlier, for the South Seas?

The value of Picasso being in Paris is proved by what happened from 1907 onwards. Earlier, he had already begun to make friends with French painters and poets — particularly with Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire. In 1907 he met Braque. What happened from then onwards is the history of Cubism. Cubism as a style was created by painters, but its spirit and confidence were maintained by poets. From 1907 to 1914 Cubism transformed Picasso — that is to say Paris and Europe transformed him. Perhaps transformed is too strong a word: Cubism gave Picasso the possibility of going outside himself, of giving his nostalgia the means to become a passionate plea, not for the past, but for the future. And this is true despite the fact that Picasso was one of the creators of Cubism. I have already said that Picasso’s Cubist period was the great exception of his life. If we are to understand how this ‘exception’ came about, and how Cubism transformed Picasso, we must now examine the historical basis of the Cubist movement.

It is almost impossible to exaggerate the importance of Cubism. It was a revolution in the visual arts as great as that which took place in the early Renaissance. Its effects on later art, on the film, and on architecture are already so numerous that we hardly notice them.

Let us compare a Cubist painting of a chair with a Fra Angelico altar-piece.

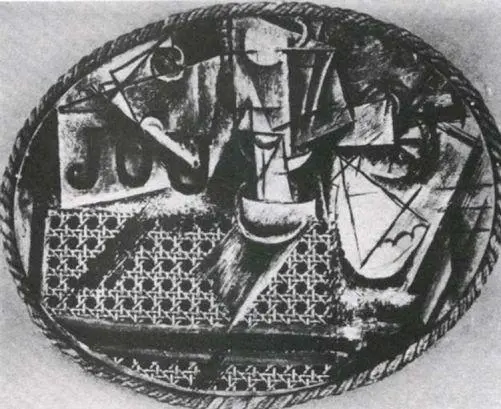

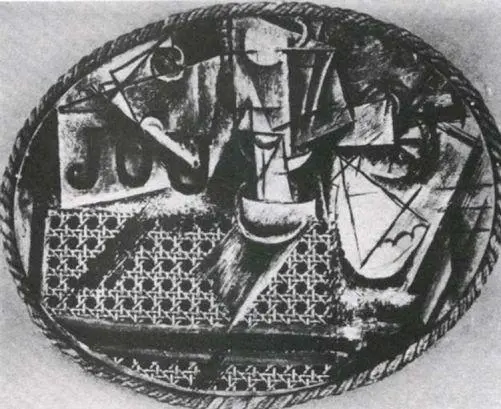

23 Picasso. Still-life with Chair-caning. 1912

The differences may at first be startling, but there are also similarities. In both paintings there is a delight in clarity. (Not necessarily a clarity of meaning, but a clarity of the forms.) Nothing comes between you and the objects depicted — least of all the artist’s temperament: subjectivity is at a minimum. In both paintings the substance and texture of the objects is freshly emphasized — as though everything was just newly made. In both paintings the space in which the objects exist is clearly very much part of the artist’s concern, although the laws of that space are very different: in the Fra Angelico the space is like that of a stage-set seen from the auditorium; in the Picasso the space is more like that of a landscape seen from the air. Lastly, in both paintings there is a simplicity and lightness, a lack of pretentiousness, which suggests an almost blithe confidence. One might think that one could find the same qualities in paintings from any period, but this is not the case. There is nothing comparable in the five centuries between.

24 Fra Angelico. The Vocation of St Nicholas (detail). 1437

The similarities between these two paintings are the result of a similar sense of disovery, of newness , which affects the world seen and the artist’s view of himself. There is scarcely any distinction, because both seem so new, between what is personal and what is impersonal.

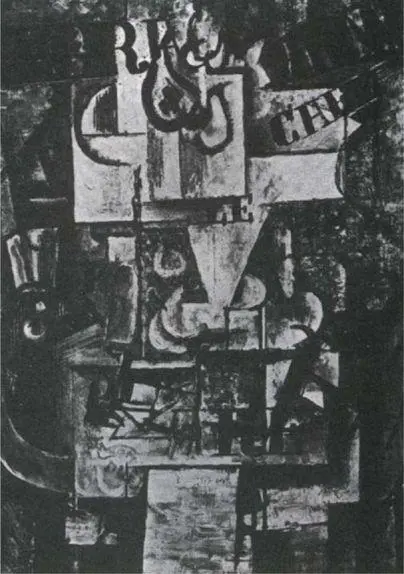

25 Picasso. The Fruit-dish. 1912

Is The Fruit-dish an exercise in a new way of seeing, a challenge to the whole history of art to date? Or is it just a view of the corner table in the café which the artist always goes to?

Such a sense of newness has nothing to do with the artist’s own originality. It has to do with the time in which he lives. More specifically it has to do with the possibilities suggested , with an awareness of promise — in art, life, science, philosophy, technology. During the early Renaissance the promise of the new humanism, the newly prosperous and forward-looking Italian city-states, the new man-centred science, lasted for about half a century — approximately from 1420 to 1480. For the Cubists the promise of the modern world lasted about seven years — from 1907 to 1914.

Читать дальше