The duende, on the other hand, does not appear if it sees no possibility of death … in idea, in sound, or in gesture, the duende likes a straight fight with the creator on the edge of the well. While angel and muse are content with violin or measured rhythm, the duende wounds, and in the healing of this wound which never closes is the prodigious, the original in the work of man.

The duende is born of hope:

The appearance of the duende always presupposes a radical change of all forms based on old structures. It gives a sensation of freshness wholly unknown, having the quality of a newly created rose, of miracle, and produces in the end an almost religious enthusiasm.

Yet it has to lead to fatality. Its most spectacular appearance is in the bullring, where death is certain.

In every country death has finality. It arrives and blinds are drawn. Not in Spain. In Spain they are lifted. Many Spaniards live between walls until the day they die, when they are taken out to the sun. A dead person in Spain is more alive when dead than is the case anywhere else…

The duende is the inspired cry of defiance of those on the rack. It is the impatience to have done, to break free from all material beginnings which appear never to develop: it is the attempt to transcend those beginnings by abandoning everything to the moment. And in certain circumstances the duende guarantees art.

At that moment La Niña de los Peines got up like a woman possessed, broken as a medieval mourner, drank without pause a large glass of cazalla, a fire-water brandy, and sat down to sing without voice, breathless, without subtlety, her throat burning, but … with duende. She succeeded in getting rid of the scaffolding of the song, to make way for a furious and fiery duende , companion of sand-laden winds, that made those who were listening tear their clothes rhythmically, like Caribbean Negroes clustered before the image of St Barbara.

La Niña de los Peines had to tear her voice, because she knew that she was being listened to by an élite not asking for forms but for the marrow of forms, for music exalted into purest essence. She had to impoverish her skills and aids; that is, she had to drive away her muse and remain alone so that the duende might come and join in a hand-to-hand fight. And how she sang!

In 1904 Picasso arrived to settle in Paris. What did he notice? How did it strike him? Or, more important, what did the impingement of all that was now around him, make him feel that he was? All definitions involve an investigation of relationships. How did Picasso have to define himself, his inner self possessed by the duende , in relation to Paris? What did Europe make Picasso become?

Ortega y Gasset is the last of the classically reactionary thinkers; he cannot, like all the dons who still apologize for capitalism and who pretend that imperialism doesn’t exist, be dismissed as an opportunist. He has been preserved in Spain as in amber, and he is acute and imaginative enough to be obsessed by the historical situation in which he finds himself. All his books are about the historical rack. I think of him because he invented a phrase which is so apt for Picasso. He is generalizing about the modern European masses. On to them he projects all his aristocratic fears of the underprivileged and uneducated. He uses the word primitive in a pejorative sense. But in the case of a truly imaginative writer, images can transcend conclusions. This is what he writes:

The European who is beginning to predominate … must then be, in relation to the complex civilization into which he has been born, a primitive man, a barbarian appearing on the stage through the trap-door, a vertical invader. 7

Picasso was a vertical invader. He came up from Spain through the trap-door of Barcelona on to the stage of Europe. At first he was repulsed. Quite quickly he gained a bridgehead. Finally he became a conqueror. But always, I am convinced, he has remained conscious of being a vertical invader, always he has subjected what he has seen around him to a comparison with what he brought with him from his own country, from the past.

I do not want to suggest that Picasso is naïve, that he was a kind of sublime but helpless farm boy like the Russian poet Yessenin (who also was a kind of prodigy). Picasso was shrewd and even cunning. He soon had the measure of the society he found himself in. And in his case there is less evidence than with any of his contemporaries, who suffered in the same way, that he was fundamentally changed or damaged by the first years of poverty and neglect. The fact that he was a vertical invader from the past was not, in any obvious way, a handicap, and it soon appeared to be an advantage. What it gave him were special standards with which to criticize what he saw.

Picasso never doubted that he had to stay in Paris. He needed Paris. He needed the example of other painters, the friends he could find there, the chance of success which it offered, its sense of modernity, its European scale. He had no illusions about Spain. He recognized that as a painter in Spain he had to deal with the middle classes and he was aware of their imprisoning provincialism. He was fully aware that Paris represented progress, and that he had his own contribution to make to that progress.

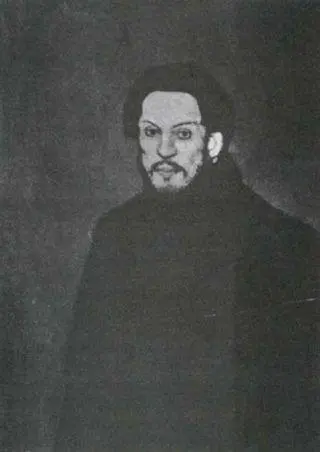

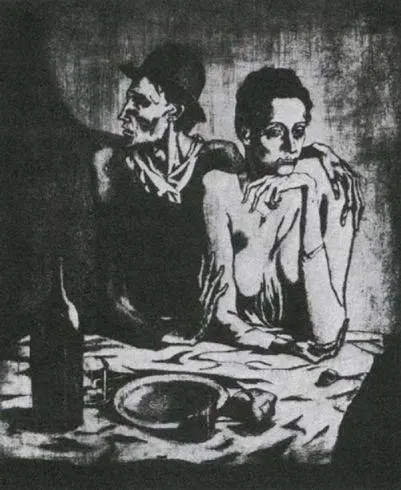

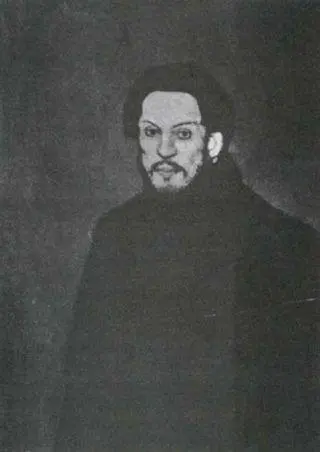

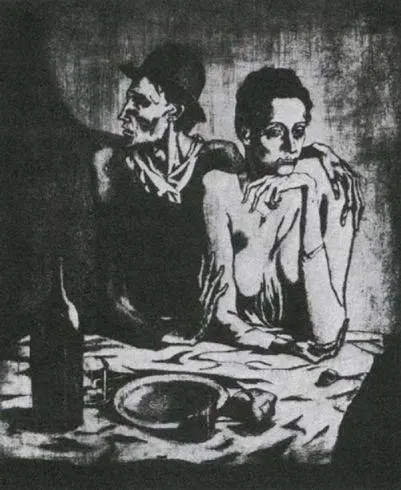

Yet at the same time this progress, as he found it working itself out in reality, horrified him. It took away with one hand what it gave with the other. Poverty is not surprising to any Spaniard. But the poverty Picasso witnessed in Paris was of a different kind. In the Paris self-portrait of 1901 we see the face of a man who not only is cold and hasn’t eaten much, but who is also silent and to whom nobody talks. Nor is this loneliness just a question of being a foreigner. It is fundamental to the poverty of outcasts in a modern city. It is the subjective feeling in the victim that corresponds exactly to the objective and absolute ruthlessness that surrounds him. This is not poverty as a result of primitive conditions. This is poverty as the result of man-made laws: poverty which, legally accepted, must be dismissed from the mind as unworthy of any consideration. 8Many peasants in Andalusia must have been hungrier than the couple at table in the etching of The Frugal Meal.

18 Picasso. Self-Portrait. 1901

19 Picasso. The Frugal Meal. 1904

But no couple would have been so demoralized, no couple would have felt themselves to be so worthless. Here is an extract from an anarchist pamphlet published in Andalusia at about the same time as this etching was made in Paris:

On this planet there exist infinite accumulations of riches which, without any monopoly, are enough to assure the happiness of all human beings. We all of us have the right to well-being, and when Anarchy comes in, we shall every one of us take from the common store whatever we need: men, without distinction, will be happy: love will be the only law in social relations. 9

The couple at the table have left such naïve hopes far behind. They would laugh outright at such innocence. But by this advance (for the anarchist hopes are unrealistic) what have they gained? What has their wider knowledge and experience brought them? A profound contempt for reality and hope, for others, and for themselves. Their only value, as Picasso sees them according to the logic of the European city, is that they represent the antithesis of the well-fed. They do not claim any rights. They scarcely claim humanity. They claim only disease with which to shame health, vulgarized and monopolized by the bourgeoisie. It is a terrible advance.

Читать дальше