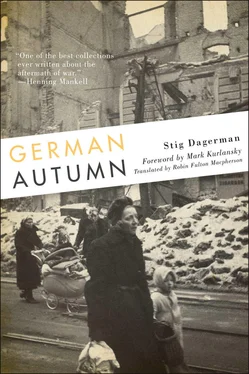

Doctors who talk to foreign interviewers about the eating habits of these families say that what they boil up in their pans is indescribable. It is not indescribable at all, any more than their whole manner of existing is indescribable. The anonymous meat which in one way or another they come across, or the dirty vegetables which they find God knows where, are profoundly unsavoury, but the unsavoury is not indescribable — only unsavoury. We can in the same way meet the objection that the sufferings which the children in these cellar-pools must undergo are indescribable. If one wants to describe them, they can be described quite perfectly — in the following way, for instance: the woman standing in the water by the stove leaves the cooking to its fate, crosses to the bed where the three coughing children lie and orders them to get off to school at once. Smoke, cold and hunger fill the cellar, and the children, who have slept fully clothed, step into the water, which laps almost over the tops of their tattered shoes, and make their way through the dark passage-way where people are sleeping, up the dark stairs where people are sleeping, and out into the chilly, wet German autumn. School does not begin for two hours yet, and the teachers tell foreign visitors about the cruelty of the parents who drive their children out on to the street. But one could argue with those teachers on the question of what kindness in this case would consist of. The Nazi aphorist wrote about the kindness of the executioner as seen in his quick, or perhaps in his well-aimed, stroke. The kindness of these parents is to be seen in the fact that they drive their children out from the water indoors to the rain out of doors, from the raw damp of the cellar to the greyness of the street.

Of course they do not go to school, partly because the school is not open, partly because ‘going to school’ is just one of those euphemisms created by necessity for those in need. They go out to steal, or to try to come across something edible by means innocent or otherwise. One could describe the ‘indescribable’ wanderings of these three children in the morning hours before school properly begins and then give a series of ‘indescribable’ pictures of their classroom activities: how slates are nailed over the windows to keep out the cold, but how these also keep out the light so a lamp has to be kept on all day but with such a dull effect that it is only with the greatest difficulty that the pupils can read whatever they are supposed to copy; how the view from the playground is surrounded on three sides by high piles of rubble (standard international variety) and how these piles of rubble also serve as school lavatories.

At the same time it would be proper to describe the ‘indescribable’ activities with which those who stay at home in their water fill their day; or the ‘indescribable’ feelings of the mother of the three hungry children when they ask her why she does not paint herself like Auntie Schulze and then get chocolate and cigarettes and tins of food from an Allied soldier. And the honesty and the moral degradation in that waterlogged cellar are both so ‘indescribable’ that this mother replies that not even the soldiers of a liberating army are so full of charity that they would put up with a dirty, worn-out and soon ageing body when the city is full of younger, stronger and cleaner bodies.

There is no doubt then that this autumn cellar was an element of the greatest consequence in the domestic politics of the time. So were the grass, the bushes and the mosses which gave a green shading to the piles of ruins in places like Düsseldorf and Hamburg. (For the third year in succession Herr Schumann walks past the ruins of the neighbouring block on his way to his work at the bank and every day he argues with his wife and his colleagues whether this greenery is to be considered as progress or decline.) The white faces of people now in their fourth year of bunker-life and so strikingly reminiscent of fish when they come up for a snatch of air, and the startlingly red faces of certain girls who several times a month are favoured with bars of chocolate, a carton of Chesterfields, fountain-pens or cakes of soap — these were readily observed facts which set their mark (although to a decreasing extent as the situation caused by the steady arrival of refugees worsened) on the previous German winter, spring and summer.

Drawing up an account is naturally rather a sad business, especially if it is sad things that must be counted, but in certain cases it has to be done. If any commentary is to be risked on the mood of bitterness towards the Allies, mixed with self-contempt, with apathy, with comparisons to the disadvantage of the present — all of which were certain to strike the visitor that gloomy autumn — it is necessary to keep in mind a whole series of particular occurrences and physical conditions. It is important to remember that statements implying dissatisfaction with or even distrust of the goodwill of the victorious democracies were made not in an airless room or on a theatrical stage echoing with ideological repartee but in all too palpable cellars in Essen, Hamburg or Frankfurt-am-Main. Our autumn picture of the family in the waterlogged cellar also contains a journalist who, carefully balancing on planks set across the water, interviews the family on their views of the newly reconstituted democracy in their country, asks about their hopes and illusions, and, above all, asks if the family was better off under Hitler. The answer that the visitor then receives has this result: stooping with rage, nausea and contempt, the journalist scrambles hastily backwards out of the stinking room, jumps into his hired English car or American jeep, and half an hour later over a drink or a good glass of real German beer in the bar of the Press hotel composes a report on the subject ‘Nazism is alive in Germany’.

The picture of the German state of mind in this third autumn which was conveyed to the outside world by this and many other journalists and foreign visitors and which thus became the general property of that outside world was of course in its way correct. They asked cellar-Germans if they had been better off under Hitler and these Germans replied: ‘Yes’. If you ask a drowning man if he was better off when he was standing up on the quay the drowning man will reply: ‘Yes’. If you ask someone starving on two slices of bread per day if he was better off when he was starving on five you will doubtless get the same answer. Each analysis of the ideological position of the German people during this difficult autumn will be deeply misleading if it does not at the same time convey a sufficiently indelible picture of the milieu, of the way of life to which these human beings under analysis were condemned. A French journalist of high repute begged me with the best of intentions and for the sake of objectivity to read German newspapers instead of looking at German dwellings or sniffing in German cooking-pots. Is it not something of this attitude which colours a large part of world opinion and which made Victor Gollancz, the Jewish publisher from London, feel, after his journey to Germany in this same autumn, that ‘the values of the West are in danger’ — values consisting of respect for the individual even when the individual has forfeited our sympathy and compassion, that is, the capacity to react in the face of suffering whether that suffering may be deserved or undeserved.

People hear voices saying that things were better before, but they isolate these voices from the circumstances in which their owners find themselves and they listen to them in the same way as we listen to voices on the radio. They call this objectivity because they lack the imagination to visualize these circumstances and indeed, on the grounds of moral decency, they would reject such an imagination because it would appeal to an unreasonable degree of sympathy. People analyse; in fact it is a kind of blackmail to analyse the political leanings of the hungry without at the same time analysing hunger.

Читать дальше