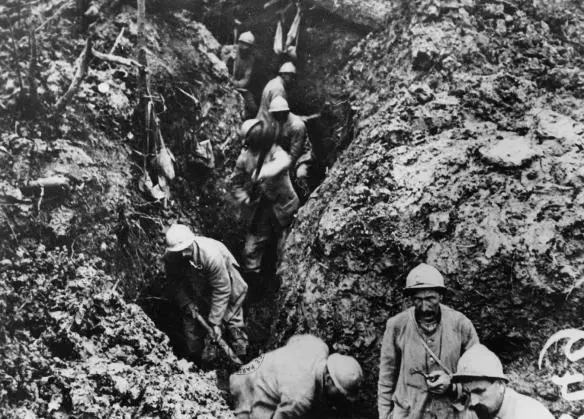

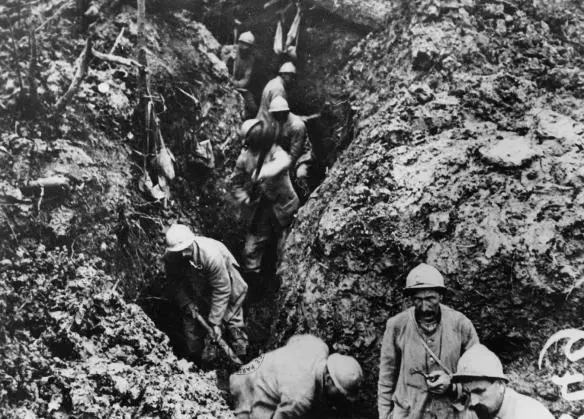

In the Trenches at Verdun, 1916. Snark/Art Resource, NY.

Although there were 850,000 European casualties of war in 1914, and two and a half million in 1915, the level of carnage reached new heights in 1916. At Verdun, General Erich von Falkenhayn, commander of German forces on the Western Front, hoped to draw French units into his “mincing machine” of heavy artillery. Falkenhayn knew that French pride would demand that Verdun be defended, though it jutted out of the French line as an awkward salient. He also knew that the French Chief of Staff, General Joseph Joffre, had neglected the defense of the old fortress. Thus, on February 21, 1916, the Germans rained 80,000 artillery shells on a fifteen-mile segment of the French line, the first of 20 million that would be fired by both sides in the battle zone by June 23 and would reduce forests to splinters and villages to rubble. The Germans easily broke through the line, so that Verdun appeared lost. Only one light railway and one road remained to supply it. Had the Germans destroyed these, they probably would have not only captured Verdun but also the entire French army stationed there, since Joffre had threatened court-martial for any officer who ordered a retreat. [6] Keegan, First World War , 278–85; B. H. Liddell Hart, The War in Outline, 1914–1918 (New York: Random House, 1936), 124–27; Hughes, Contemporary Europe , 61–62.

The French sent General Henri-Philippe Petain to command Verdun at this point. Besides inspiring confidence in his soldiers, Petain also widened the supply lanes to Verdun, so that it could be supplied and reinforced safely. The French also benefited from the willingness of the British to assume more of the Western Front, thus freeing more French soldiers to reinforce the fort, as well as from an Italian offensive on the Isonzo River in northern Italy and a Russian offensive at Lake Narocz in Lithuania, both of which distracted the Germans. [7] Liddell Hart, War in Outline , 127; Hughes, Contemporary Europe , 62.

Although the French managed to hold the old fortress in the Battle of Verdun, over 200,000 men were killed on each side. A Frenchman who participated in that campaign wrote, “The bread we ate, the stagnant water we drank, everything we touched had a rotten smell, owing to the fact that the earth around us was literally stuffed with corpses.” It was the only prolonged offensive on the Western Front in which the attacking side did not lose more troops than the defending party. This anomaly was the result of the German practice of sending “advance groups,” guinea pigs whose sole function was to draw enemy fire, in order to ascertain the location of least resistance along the front before the main force was committed to battle. [8] Liddell Hart, War in Outline , 125; Hughes, Contemporary Europe , 63; Keegan, First World War , 285; Ellis, Eye-Deep in Hell , 59.

Douglas Haig, who had become Commander of the British Expeditionary Force in France in December 1915, was not disturbed by the extent of the French losses at Verdun. Believing that his own troops would succeed where the French had failed, Haig planned a summer offensive along the Somme that would be dominated by British soldiers. [9] Liddell Hart, War in Outline , 113; Keegan, First World War , 289.

Everything went wrong. Haig was “overruled by his commanders” when he suggested using advance groups as the Germans had at Verdun. In the Allies’ opening bombardment, 1500 guns fired one million shells, but only 450 of these guns were heavy artillery, the type necessary for destroying the concrete machine gun nests of the Germans. Also, Haig’s field commander made matters worse by selecting an area of bombardment that was too wide, so that some machine gun nests were completely untouched when Allied troops advanced towards them on July 1, 1916. Furthermore, the French overruled British proposals that the attack be made at or before dawn, contending that their artillerymen required “good observation” for firing. The result, of course, was good observation for the many German machine gunners who had been largely unaffected by the preliminary bombardment. In addition, the British infantrymen were ordered to attack in close formation—in the words of military historian B. H. Liddell Hart, “symmetrically aligned, like rows of nine-pins ready to be knocked over.” Each soldier carried sixty-six pounds of equipment on his back. It was “difficult to get out of a trench, impossible to move much quicker than a slow walk.” Although the gaps that the British had cut in their own wire in preparation for the attack facilitated German targeting of their troops, aiming was largely unnecessary. A German machine gunner recalled, “When we started firing, we just had to load and reload. They went down in their hundreds. You didn’t have to aim, we just fired into them.” [10] Liddell Hart, War in Outline , 130–35; Hughes, Contemporary Europe , 63; Keegan, First World War , 291–96.

On the first day alone the British lost nearly 60,000 men. The Allies corrected only some of their tactical errors and continued the offensive. By the time November mud ended the Somme offensive, the British had experienced the greatest military catastrophe in their history, suffering 420,000 casualties, the French 194,000, and the Germans over 600,000. The German total would not have been so high had not a German general, emulating the Allies, ordered that every yard lost be taken by counterattack. [11] Liddell Hart, War in Outline , 138; Hughes, Contemporary Europe , 63; Keegan, First World War , 295, 299.

Both the French and the British failed to learn the lessons of 1916. In 1917 French General Robert Nivelle launched a new offensive on the Western Front that was equally disastrous. The Germans shrewdly adopted a tactic of “defense in depth” that left the front line almost empty, while an intermediate zone behind was held by machine gunners stationed in shell holes and other strong positions, and the real strength of the defense lay in reserves deployed outside artillery range 10,000–20,000 yards behind the front. The resulting casualties were so demoralizing that French soldiers launched a mutiny, a sort of military strike in which they pledged to defend their own trenches but refused to continue attacking the enemy’s. [12] Keegan, First World War , 322, 330.

Nevertheless, the imperturbable Haig persuaded the reluctant British War Cabinet to approve a new offensive in Flanders for 1917. Liddell Hart later charged that Haig was able to secure permission by promising not to engage in an all-out assault on German positions but rather to take a gradual approach that he had already categorically ruled out in conversations with his own generals. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George opposed the offensive, saying, “We shall be attacking the strongest army in the world, entrenched in the most formidable positions with an actual inferiority of numbers. I do not pretend to know anything about the rules of strategy, but curious indeed must be the military conscience which could justify an attack under such conditions.” Yet the War Cabinet approved the offensive, due partly to the desire to capture German submarine bases in Belgium. [13] Liddell Hart, War in Outline , 184–85, 189, 191.

According to Liddell Hart, Haig’s second deception occurred after the offensive began. In order to gain a continuation of the offensive, which was obviously failing miserably, Haig grossly exaggerated the number of enemy casualties in his reports to the War Cabinet. Before Haig guided Lloyd George on a tour of his “prisoner cages,” he replaced healthy German prisoners with gaunt ones in order to demonstrate the success of the offensive in demoralizing and debilitating the Germans. [14] Ibid., 195–96.

Читать дальше