Acknowledgments

I would like to thank James Dormon, Reinhart Kondert, Matthew Schott, and Amos Simpson, all of whom gave me sound advice and encouragement when I first undertook this subject in the 1980s. I would also like to express my gratitude to my colleagues Chad Parker, Chester Rzadkiewicz, and Eran Shalev, who read a more recent version of the manuscript and provided valuable insights. Additionally, I would like to thank my editor, Susan McEachern, for her unfailing enthusiasm and wisdom. As always, I would like to thank my precious wife, Debbie, my other half, for her unceasing prayers and support.

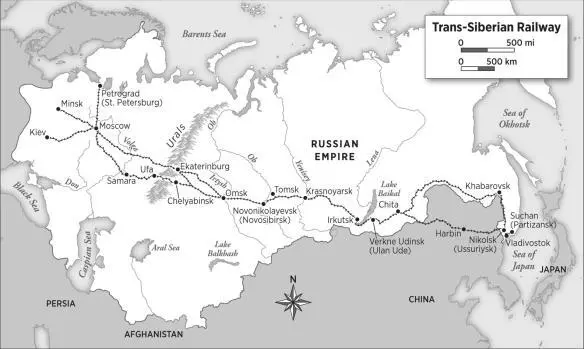

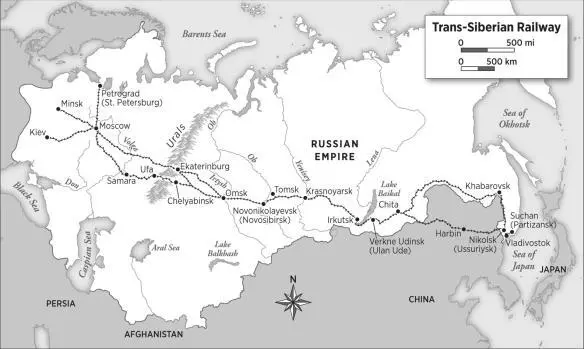

The Trans-Siberian Railway

CHAPTER ONE

The War to End All Wars

Only the dead have seen the end of war.

—George Santayana

[1] George Santayana, Soliloquies in England (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1924), 102.

From 1914 to 1918 the nations of Europe focused their intelligence and energy on the perfection of the science of killing. Nations that had taken immense pride in calling themselves civilized were engaged in a campaign of slaughter on a scale that was unprecedented in the history of humankind. The number of young lives snuffed out in the struggle that was called “The Great War,” before people began numbering their world conflicts, easily surpassed that of all previous wars.

To understand almost any twentieth- or twenty-first-century subject without understanding what occurred in World War I is difficult, if not impossible. It is like trying to comprehend the late medieval period while ignoring the Great Plague. In addition to inaugurating modern warfare (tanks, machine guns, airplanes, and submarines all made their first appearance on a large scale in this war), the Great War had enduring political effects. The unprecedented carnage of the war led the Allies to impose the harsh Treaty of Versailles on Germany, which led, in turn, to the rise of Adolf Hitler and World War II. The war also led to the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, which led, in turn, to a Cold War that lasted nearly half a century.

Like these other developments, the Siberian intervention finds its origin in the events of World War I. The disasters of that war eventually led to the departure of American soldiers for the distant land of Siberia.

Numerous volumes have been written to dispute the causes of World War I. Suffice it to say that there were many causes. Several powerful ideologies of the nineteenth century, such as nationalism, imperialism, militarism (increased by ignorance of the lethal nature of modern warfare since Europe had not suffered a general war in a century and its generals refused to learn the lessons of the U.S. Civil War, the Boer War, and the Russo-Japanese War), and fatalism about the inevitability of war spawned by Social Darwinism all played key roles, as did poor leadership and the development of alliance systems. By the start of the war in 1914 the Allies, which included Great Britain, France, and Russia (joined by Italy in 1915), were arrayed against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey. Far from fostering peace, as expected in traditional balance of power theory, this balance actually encouraged war because each side became confident in its ability to win. Finally, the military strategies of both sides called for preemptive strikes, thereby making war more likely than peace after the onset of a crisis, as each side rushed to implement its strategy ahead of its opponent. For instance, Germany’s Schlieffen Plan centered on knocking France out of the war in the West before turning to face Russia in the East. Thus, the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, by a Bosnian nationalist, with the connivance of some members of the Serbian government, set in train a cascade of events that led inexorably to war. When the Austrians moved to invade Serbia, Russia mobilized its massive forces to help its traditional ally, prompting Germany to mobilize its own forces and initiate the Schlieffen Plan out of the fear that a Russian invasion of Germany would end all hope of averting a two-front war. The German invasion of Belgium in preparation for the invasion of France, in turn, led both France and Britain to declare war against Germany. [2] For brief but competent discussions of the origins of World War I, see John Keegan, The First World War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), 30, 52–69; H. Stuart Hughes, Contemporary Europe: A History (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1961), 24–34.

Trench Warfare and Its Consequences

Ten million men were killed in World War I. France lost 17 percent of its soldiers, 1.7 million out of a little over nine million. Russia also lost 1.7 million men, Britain one million, Germany two million, and Austria-Hungary 1.5 million. The bodies of more than half of those killed in the West, and an even higher percentage in the East, were never recovered. Many survivors were badly mutilated. [3] Keegan, First World War , 3, 5–7, 421–23.

One reason that the casualties were so numerous is that the trench warfare that characterized the Western Front heavily favored the defensive, so that it was extremely difficult for an attacker to make any progress. When the Germans were stopped short of Paris on the Marne River, they retreated and entrenched themselves on favorable ground. Within a brief time, both sides possessed a line of trenches that extended 475 miles from the North Sea to neutral Switzerland, a line that changed little for almost three years. The ten-foot-deep trenches were fronted by massive entanglements of barbed wire and backed by an increasingly elaborate system of reserve trenches connected by communications trenches that extended for miles, a system so complicated it soon required guides and street signs. Whenever one side attacked, its massive artillery barrage generally accomplished little except to ruin any chance of achieving surprise. (Since telephone and telegraph wires were almost always immediately destroyed in the opening bombardment, and primitive radios, which could not yet transmit voices, only Morse code, and relied on massive batteries, were too slow to be useful and too unwieldy to be carried into battle, armies were forced to use such primitive means as flags, runners, and carrier pigeons to transmit the information necessary to target and retarget their artillery barrages accurately.) Attacking infantrymen crawled out of their own trenches, carrying sixty to eighty-five pounds of equipment on their backs (at a time when the average recruit weighed only 132 pounds), and marched across the “no man’s land” of a few hundred yards that normally rested between the trenches to almost certain death, mowed down by rifle fire and machine guns while attempting to cut through dense tangles of barbed wire that were sometimes over a hundred yards deep. Even when the attackers managed to take the opposing trenches, they were almost immediately set upon by fresh, lethal reserves. [4] Ibid., 22, 137, 162, 176–78, 183, 316; John Ellis, Eye-Deep in Hell: Trench Warfare in World War I (New York: Pantheon, 1976), 10, 12, 16, 24–25, 33, 83, 85–91.

Nevertheless, the military cultures on both sides were painfully slow to abandon their semi-mystical, Napoleonic faith in “the spirit of the offensive,” which taught that a determination to continue attacking despite heavy casualties would bring victory. This stubbornness was exacerbated by the rareness with which top-ranking generals visited the front lines and their obliviousness when they did so. A British soldier wrote: “A fortnight after some exploit, a field-marshal or a divisional general comes down to a battalion to thank it for its gallant conduct, and fancies for a moment, perchance, that he is looking at the men who did the deed of valour, and not a large draft that has just been brought up from England and the base to fill the gap. He should ask the services of the chaplain and make his congratulations in the grave-yard or go to the hospital and make them there.” [5] Ellis, Eye-Deep in Hell , 91, 197.

Читать дальше