Ommanney was referring to the possibility that some of the canned food was spoiled, or in his words, represented a “putrid abomination.” Sherard Osborn also noted angrily that “their preserved meats were those of the miscreant, Goldner.” Tinned-food supplier Stephan Goldner had had quality control problems with provisions supplied to later expeditions. In January 1852, it was reported that an examination at Portsmouth of a consignment of Goldner’s preserved meat (delivered fourteen months earlier), revealed that most of the meat had putrefied. According to the Times: “If Franklin and his party had been supplied with such food as that condemned, and relied on it as their mainstay in time of need, the very means of saving their lives may have bred a pestilence or famine among them, and have been their destruction.” Even before the Franklin expedition had sailed, Commander Fitzjames expressed concern that the Admiralty would buy meat from an unknown supplier simply because he had quoted a lower price. Indignation over the spoiled meat led to an inquiry, however it concluded that Goldner’s meat had been satisfactory on previous contracts. Wrote one Admiralty official: “From that period (1845) Goldner’s preserved meats have been in constant use in the navy, and it is only, I believe, latterly that they have been found to consist of such disgusting material.”

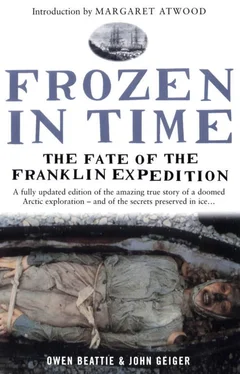

Dr. Peter Sutherland, surgeon on Penny’s expedition, believing some important clues to the health and the fate of Franklin’s expedition might be harboured within the graves, proposed their exhumation:

It was suggested to have the graves opened, but as there seemed to be a feeling against this really very proper and most important step, the suggestion was not reiterated. It would have been very interesting to have examined into the cause of death; it is very probable there would be no difficulty in doing this, for the bodies would be found frozen as hard as possible, and in a high state of preservation in their icy casings.

Sutherland went on to speculate on possible causes of death for the three sailors:

The cause of Braine’s death, which happened in April, might have been scurvy supervening upon some other disease. The first two deaths had probably been caused by accidents, such as frost bite or exposure to intense cold in a state of stupor, or to diseases of the chest, where there might have been some latent mischief before leaving England, which the changeable weather in September and October rekindled, and the intense cold of November and December stimulated to a fatal termination.

In August 1852, a squadron of ships returned to Beechey Island, and the searchers resumed their research there, but these further investigations were hampered by the frenzied activity that had taken place at the time of the discovery of Franklin’s first winter quarters two years earlier. Sherard Osborn, in a communication to the Royal Geographical Society, wrote of the destruction of the site:

after a couple of hundred seamen had, in 1850, turned everything topsy-turvy, and carried and dropped things far from where they were originally deposited, those who first visited the place in 1852 can have but little idea of what the place was like when we found it as it had been left by the ‘Erebus’ and ‘Terror’.

Together, the rescue vessels had traced the first season of Franklin’s voyage from its disappearance into silence down Lancaster Sound in August 1845 until as late as September 1846. At most, searchers had found at Beechey Island only a partial record of the expedition’s first year beyond the reach of civilization. No one knew where to look next.

Ironically, Franklin’s failure launched the golden era of Arctic exploration. More than thirty ship-based and overland expeditions would search for clues as to Franklin’s fate over the course of the following two decades, charting vast areas and mapping the completed route of the Northwest Passage in the process. Whilst many of these search expeditions were funded by the British government in response to public demand that Franklin be saved, others were raised by public subscription following appeals from Lady Franklin. Seamen volunteered for Arctic service in droves. Yet contemporary journals make it clear that many of these searches were also crippled by illness. In this respect, James Clark Ross was not alone.

Indeed, there was a more sinister enemy on board these Arctic voyages than the usual complaints of frostbite and stifling boredom. Where one captain, George Henry Richards, reported the “general debility” afflicting his crew, another, Sir Edward Belcher, abandoned four of his five ships in order to escape the far north after two years, fearing that a third Arctic year would lead to large-scale loss of life. The crew of another ship, the Prince Albert, a privately funded expedition, suffered severely from scurvy during their lone winter, 1851–52. And on the Enterprise, Captain Richard Collinson waged a bitter internecine war with his crew; by the end of his command he had placed, amongst others, his first, second and third officers under arrest. When he was subsequently criticized for his conduct, Collinson blamed “some form of that insidious Arctic enemy, the scurvy, which is known to effect the mind as well as the body of its victims.”

When another ship, the Investigator, commanded by Captain Robert McClure, became trapped at Mercy Bay on Banks Island, several of the men aboard went mad and had to be restrained, their howls piercing the long nights. The crew carried lime juice, specially prepared by the Navy’s Victualling Department, and hunted and gathered scurvy grass in the brief Arctic summers. By these methods, McClure was able to forestall the appearance of scurvy, but by the third winter, illness was widespread: “only 4 out of a total of 64 on board were not more or less affected by scurvy.” Alexander Armstrong, expedition surgeon, described treating sufferers with “preserved fresh meat,” as tinned foods were still considered to have antiscorbutic properties. Even after such interventions, three of the men died. McClure abandoned ship, and his crew were spared only by a fortuitous encounter with yet other search ships. Thomas Morgan, who was seriously ill at the time of this rescue, “sick and covered with scurvy sores,” died on 19 May 1854. He was buried on Beechey Island, alongside the men from the Erebus and Terror.

Yet McClure, who was credited with the first successful transit of the Northwest Passage, even without his ship, was glad for the struggle he had been put through. He, like others of the age, saw self-sacrifice in some noble cause as the pinnacle of human achievement. He captured the spirit of the Franklin searchers this way:

How nobly those gallant seamen toiled… sent to travel upon snow and ice, each with 200 pounds to drag… No man flinched from his work; some of the gallant fellows really died at the drag rope… but not a murmur arose… as the weak fell out… there were always more than enough volunteers to take their places.

By far the worst afflicted, however, were two Franklin search expeditions funded by Henry Grinnell, a wealthy American benefactor. The first, commanded by Lieutenant Edwin de Haven of the U.S. Navy, aboard the Advance and the Rescue, went out in May 1850 and by August was already trapped in winter quarters with temperatures plummeting. Elisha Kent Kane, the ship’s surgeon and the scion of a wealthy Philadelphia family, described the appalling living conditions endured by the crew:

…within a little area, whose cubic contents are less than father’s library, you have the entire abiding-place of thirty-three heavily-clad men. Of these I am one. Three stoves and a cooking galley, three bear-fat lamps burn with the constancy of a vestal shrine. Damp furs, soiled woolens, cast-off boots, sickly men, cookery, tobacco-smoke, and digestion are compounding their effluvia around and within me. Hour by hour, and day after day, without even a bunk to retire to or a blanket-curtain to hide me, this and these make up the reality of my home.

Читать дальше