Top Secret

To Comrade Stalin

To Comrade Molotov

On 16 June 1945, the NKVD of the USSR, under Number 702/b, presented to you and Comrade Stalin the copies received from Berlin via Comrade Serov of the records of the interrogations of certain members of the entourage of Hitler and Goebbels concerning the last days of Hitler and Goebbels’ time in Berlin as well as copies of the description and the files of the medico-legal examination of what are presumed to be the corpses of Hitler and Goebbels and their wives.

Nothing’s missing: not the big historic names of Stalin, Hitler, and Goebbels, nor the abbreviations NKVD and USSR. And this was only the beginning. Other names and other equally resonant abbreviations would haunt Lana and me during the months of this investigation like so many ghosts emerging from an accursed past. On the German side: Himmler, the SS, Göring, the Third Reich… On the Soviet side: Beria, Molotov, the Red Army, Zhukov…

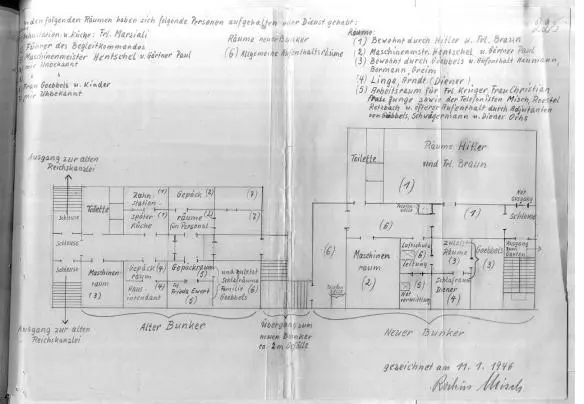

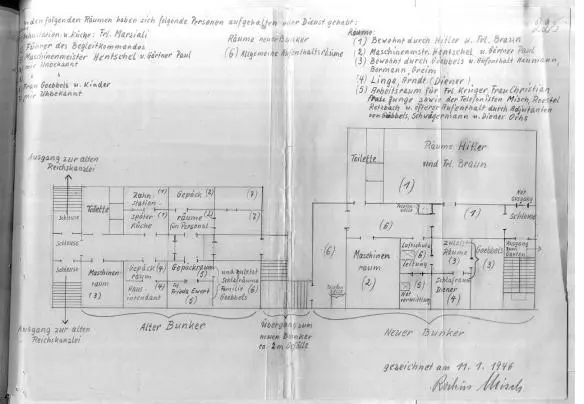

As well as these reports, we have collected a series of captioned photographs and some drawings, including diagrams of Hitler’s bunker. They are drawn in pencil on paper by prisoners, SS men, all members of the Führer’s inner circle. They had been ordered to draw them by the Russian special services. The aim was to understand how life was organised in their enemy’s air-raid shelter. Everything is precisely annotated: the apartments of the Nazi dictator, Eva Braun’s bedroom, her bathroom, the conference room, the toilets…

Diagrams of the Führerbunker (GARF)

The mass of documents in the GARF collection includes several dozen pages in German. Some interrogations of Nazi prisoners have been transcribed directly in their language and by hand as most of the Red Army typewriters used Cyrillic characters. Luckily, the handwriting of the Soviet interpreters is still quite legible. Except in one particular case, in which the letters look like the scrawls of a spider, not to mention the many crossings-out. These barely decipherable texts wore out the eyes of two of my German-French translators. The first ended up throwing in the towel. As for the second, he asked me not to rely on him in the future if the situation came up again. Their determination was not in vain: thanks to them, I was able to place this document within the great historical puzzle formed by the Russian archives of the Hitler file. These spidery squiggles record the interrogation of a man by the name of Erich Rings, one of the radiographers in Hitler’s bunker. In particular, Rings gives an account of the moment when his superiors asked him to pass on a message about the Führer’s death: “The last telegram of this kind that we have communicated dates from 30 April, at around 5:15 pm in the afternoon. The officer who brought the message told me, so that we would also be informed immediately, that the first phrase of the message was as follows: ‘Führer deceased!’”

If Rings is telling the truth, this information implies that the German dictator’s death occurred before 5:15 pm on 30 April 1945. But might the Nazi radiographer have been lying to the Soviet investigators? They assume that he might. Suspicion is the essence of any good spy. It is a great asset in all circumstances, and allows them to climb through the ranks of their hierarchy with confidence. Suspecting the enemy, his declarations, including those made under torture. Still, this systematic attitude does obstruct the progress of the inquiry. And my own work, too. The texts that I have in front of me concern a period of almost twelve month, leading up to the middle of 1946. So, almost six months after the fall of Berlin on 2 May 1945, the officers in charge of the Hitler file still hadn’t completed their investigation. They asked the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs to grant an additional delay. As well as the transfer of certain German prisoners from Russian prisons to Berlin. The aim was to reconstruct Hitler’s last hours.

10 April 1946 Top Secret

To the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Comrade S.N. Kruglov.

Within the context of the investigation into the circumstances of the disappearance of Hitler on 30 April 1945, the following are currently held in Butyrka Prison [in Moscow]:…

This is followed by a long list of Nazi prisoners; then the document resumes:

In the course of the investigations into these individuals, apart from the contradictions causing doubts about the plausibility of the version of Hitler’s suicide already given to us, certain additional facts have been revealed, which must be examined on the spot.

In this respect, we think that the following arrangements should be put in place:

All individuals arrested in this case must be sent to Berlin.

[…]

Give the task force the job of investigating, within a month, all the circumstances of the disappearance of Hitler and to deliver a report on the subject to the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR.

Give Lieutenant General Bochkov the task of organising the accompaniment of prisoners under escort, and to allocate to that end a special wagon for the inmates to the city of Brest [in present-day Belarus]. The accompaniment of the prisoners under escort from Brest to Berlin will be undertaken by the Berlin task force.

For the study of pieces of evidence and the scene of the incident, send to Berlin the qualified criminal investigator of the General Directorate of the Militia of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR, General Ossipov.

The letter is signed by two Soviet generals based in Berlin.

April 1946. Why did the investigation into Hitler take so long? What happened in the bunker? The Russians devoted such energy to investigating that truth that escaped them. And yes, more than any other Allied army (the Americans, the British and the French), Soviet troops had taken hundreds of eyewitnesses of the fall of Berlin and the Führer prisoner. Witnesses who were put severely to the test by their jailers. I can see that determination to solve this mystery just below the surface of many of the reports and interrogations. The same questions keep returning, the same threats. Why not simply accept the evidence? Why can’t Stalin and his men admit that the prisoners are telling the truth? I would have made a very bad member of the Soviet secret police. The proof lies in this confrontation between two SS prisoners who were close to Hitler.

The first is called Höfbeck and is a sergeant, the other is called Günsche and is an SS officer.

Question to Höfbeck:Where were you and what did you do on 30 April 1945? The day when, according to your statement, Hitler took his life?

Höfbeck’s reply:On 30 April 1945 I was posted to the emergency exit of the bunker by my departmental head, State Councillor [Regierungsrat Högl, head of a group of nine men].

Question to Höfbeck:What did you see there?

Höfbeck’s reply:At 2:00 pm, or perhaps a little later, as I approached, I saw several people […]. They were carrying something heavy wrapped in a blanket. I immediately thought that Adolf Hitler must have committed suicide, because I could see a black pair of trousers and black shoes hanging out on one side of the blanket. […] Then Günsche shouted: “Everyone out! They’re staying here!” I can’t say for definite that it was Günsche who was carrying the second body. The three other comrades immediately ran off, I stayed near the door. I saw two bodies between one and two metres from the emergency exit. Of one body, I was able to see the black trousers and the black shoes, of the other (the one on the right) the blue dress, the brown socks and shoes, but I can’t say with any certainty. […] Günsche sprinkled petrol over the bodies, and someone brought him a light near the emergency exit. The farewells didn’t take long, five to ten minutes at most, because then there was some very heavy artillery fire. […]

Читать дальше