True to form however, the weeks leading up to the Frank’s departure from Nuremberg were not without incident, intrigue and adventure, and the following examples are further evidence of how closely, at times, he sailed to the wind, and how he was never slow to take advantage of each and every opportunity that presented itself.

The first of those incidents concerned Wolfe’s Opal car. The US Army had suddenly declared that all motor vehicles captured during hostilities would have to be registered under newly created occupation plates, and proof would be required to show where and when the vehicle had been captured. To get over this little problem Wolfe persuaded a departing BBC executive to provide a letter stating that he had captured the vehicle near Tobruk and had sold it to Frank. The necessary endorsement, exit permit and fuel allowances were then provided by a departing US major who told Frank as he was going home tomorrow he was prepared ‘to sign anything put in front of him.’

At about the same time Wolfe’s driver knocked down and killed an elderly German. In an off-the-record discussion – that seems astonishing but was perhaps indicative of the awful times the Germans were living through – the representative of the insurance company handling the case said to Frank: ‘The family were really rather glad to get rid of the old man who was eating and not producing. They would sign a total release for twenty cartons of cigarettes. He could not do it on behalf of his company, but – would you?’ Wolfe then records, ‘I did. Twenty cartons of cigarettes cost me roughly $18 at the PX. Not much to compensate for the loss of a life.’

The third incident involved Wolfe and two friends, Fredy Stoll, [1] Alfred ‘Fredy’ Stoll was a ski jumper born in Berchtesgaden who became the German champion in 1934. On that occasion he was awarded an engraved cup by Hermann Goering as a special prize for the furthest jump of the day. He was described as being ‘a daredevil without fear, who not only jumps further than anybody else, but, by testimony of a friend, would also make a good race car driver and motorbike racer.’

the former German ski-jumping champion and Fritz Haegele, Goering’s valet, who was being employed by the US as caretaker of the ‘Eagles Nest’, Hitler’s famous mountain retreat near Berchtesgaden, where Wolfe and others would often retreat themselves to cook meals on ‘Hitler’s stove.’ The three had been stripping the Nest of certain items – in particular three large bathtubs – when Stoll was arrested by the CIC, who had been tapping Haegele’s phone. They suspected Stoll of looting much more than bathtubs, namely the art treasures and jewels that Goering had stolen from the Jews and hidden away. When they heard Haegele tell Stoll ‘The stuff’s ready’ they swooped believing they had hit the jackpot. The CIC officers were not happy when all that could be found in Stoll’s van was a bathtub and, following a Frank intervention, Stoll was released without charge and allowed to keep Hitler’s bathtub; about which Wolfe comments: ‘I have often soaked in it, and it was sheer luxury.’

In late 1947 Wolfe and Maxine departed Nuremberg under the cover of darkness, in their two cars and a trailer which bore a variety of false number plates and were covered by forged documents, to spend the winter in Davos before moving on, in May 1948, to Paris where Wolfe became a script writer for the radio section of the Marshall Plan. [2] The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Programme) was an American initiative. Named after US Secretary of State George Marshall, the Plan gave $13 billion in aid to help rebuild Western European economies after the Second World War.

They moved on to London in July, where they were joined by Maxine’s ‘incurable alcoholic and divorced mother Gladys’. Although fifty-four years of age (and in Maxine’s absence) Gladys stripped off and invited Wolfe to put her bra on – an invitation he turned down. He later informed Maxine of what had taken place. The whole episode was to later have disastrous repercussions on the Frank marriage, as Wolfe says: ‘The words Gladys uttered at the time were ominous: “I’ll get you for this you son-of-a-bitch” – she sure as hell did’.

By 1948 Wolfe was a partner in Fellowes & Frank, an import-export company and an adviser to a firm of aircraft brokers. However, business was not good, and Wolfe had become seriously concerned about the way Germany appeared to be hoodwinking the rest of the world with the information it was providing through the media. This led to another great episode in the Wolfe Frank story that was to once again put his life at risk and led to him going under cover on false papers into the occupied East and West sectors of Germany, to gather evidence for what became an acclaimed series of articles for the New York Herald Tribune ( NYHT ) entitled ‘Hangover After Hitler’ . During the covert operation, he single-handedly discovered, unbelievably working in a position of trust for the British Property Control Board [3] Following the war many German owned properties and estates were seized by the British Property Control Board and handed over to reliable Germans or were held by the Board until the Control Council decided how to dispose of them in the interests of peace.

under an assumed name, the SS officer who was ‘fourth’ on the Allies most wanted list of war criminals. Wolfe eventually turned the former Nazi general over to the appropriate authorities but not before he had taken his signed ‘Confession’. Of the two copies produced one was handed in as evidence (along with the SS officer) whilst the other signed copy remains in the Wolfe Frank archive along with his memoirs and other documents of importance.

The astonishing story of Frank’s clandestine undercover operation, the articles he wrote, his apprehending of the Nazi general and, for the first time, a translation and reproduction of the entire Confession are to be the subject of a separate book entitled The Undercover Nazi Hunter: Unmasking Evil in Post-war Germany , which is to be published by Frontline Books. (A copy of the NYHT flyer announcing the Hangover After Hitler series can be seen on page 194).

42. EPILOGUE

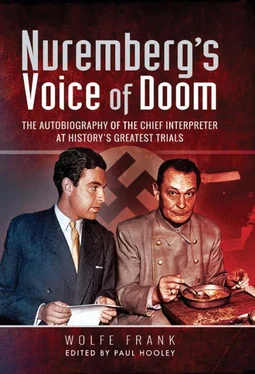

Any follower of the Wolfe Frank story thus far would be forgiven for thinking that such a man might consider his involvements at Nuremberg, and his post-war undercover assignment and single-handed apprehension of one of the ‘most wanted’ Nazi war criminals, to have been something extraordinary, and that the rest of his life might prove to be something of an anti-climax. Certainly, in today’s world, such service to one’s country would be more appropriately recognized, and the accompanying media coverage would guarantee that those achievements were more publicly acknowledged and rewarded. Together with his striking good looks, his personality, his charisma, his ability and his intelligence, these qualities would make a modern-day Wolfe Frank a PR management company’s dream client – and would, no doubt, lead to him being considered a ‘hot property’ with the potential of having his profile raised to the kind of ‘superstar’ status many less able and less talented ‘personalities’ enjoy today.

However, whilst those events were undoubtedly two of the highlights in a quite extraordinary life, Wolfe viewed them as being no more than transitory events from which, once over, he quickly moved on – without much more than the occasional backward glance. To him they were simply two of the challenges destiny had set him during a lifetime in which he more than fulfilled Rudyard Kipling’s counsel to ‘fill every unforgiving minute with sixty seconds worth of distance run’.

Читать дальше