Tom Phillips - Humans - A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tom Phillips - Humans - A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Toronto, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Hanover Square Press, Жанр: История, Юмористические книги, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hanover Square Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:Toronto

- ISBN:978-1-48805-113-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

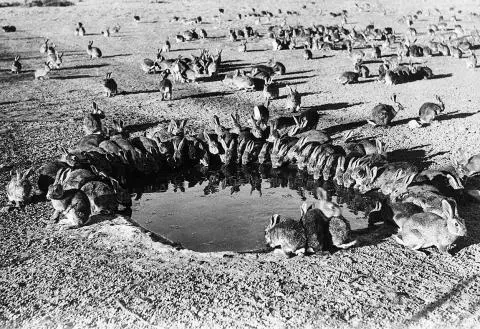

It didn’t stay in the thousands. A decade after Austin introduced them, two million rabbits were being shot each year in Victoria without denting their population growth in the slightest. The rabbit army soon spread all across Victoria, moving at an estimated 80 miles a year. They were seen in New South Wales by 1880, in South Australia and Queensland by 1886, Western Australia by 1890 and the Northern Territory by 1900.

By the 1920s, at the height of the rabbit plague, Australia’s rabbit population was estimated at 10 billion. There were 3,000 of them for every square mile. Australia was quite literally covered in rabbits.

The rabbits didn’t just breed; they ate (breeding is hungry work, after all). They stripped the land bare of vegetation, driving many plant species into extinction. The competition for food brought a number of Australian animals to the brink of extinction, as well, while without plant roots to hold the soil together the land itself crumbled and eroded.

The scale of the problem was clear by the 1880s, and authorities were at their wits’ end. Nothing they tried seemed to be capable of stopping the floppy-eared onslaught. The government of New South Wales placed a slightly desperate-sounding advertisement in the Sydney Morning Herald , promising to pay “the sum of £25,000 to any person or persons who will make known… any method or process not previously known in the Colony for the effectual extermination of rabbits.”

Over the following decades, Australia tried shooting, trapping and poisoning the rabbits. They tried burning or fumigating their warrens or sending ferrets into the tunnels to flush them out. In the 1900s, they built a fence over a thousand miles long to try and keep the rabbits out of Western Australia, but that didn’t work because it turns out that rabbits can dig tunnels and, apparently, learn to climb fences.

Australia’s rabbit problem is one of the most famous examples of something that we’ve only figured out quite late in the day: ecosystems are ridiculously complex things and you mess with them at your peril. Animals and plants will not simply play by your rules when you casually decide to move them from one place to another. “Life,” as a great philosopher once said, “breaks free; it expands to new territories and crashes through barriers—painfully, maybe even dangerously. But, uh, well, there it is.” (Okay, it was Jeff Goldblum in Jurassic Park who said that. As I say, a great philosopher.)

Ironically, after the initial fuck-up of introducing rabbits into Australia in the first place, the eventual solution was also a fuck-up. For several decades Australian scientists had been experimenting with using biological warfare on the rabbits: introducing diseases in the hope that they’d be killed off, most famously myxomatosis in the 1950s. That worked pretty well for a while, reducing the rabbit population dramatically, but it didn’t stick. It relied on mosquitoes to transmit the virus, so wasn’t effective in areas where mosquitoes wouldn’t breed, and eventually the surviving rabbits developed resistance to the disease and numbers started climbing again.

But the scientists carried on researching new biological agents. In the 1990s, they were working on rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus. Now, experimenting with diseases is a dangerous business, and so the scientists were doing their work on an island off the south coast, to reduce the risk of the virus getting loose and spreading to the mainland. Go on. Guess what happened.

Yep, in 1995, the virus got loose and spread to the mainland. Life broke free, in this case by hitching a ride on some flies. But having accidentally released a deadly (to rabbits) pathogen into the wild, the scientists were rather pleased to note that… it seemed to be working. In the twenty years since rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus was mistakenly released into the wild, rabbit populations in South Australia have declined again, while vegetation has returned and the many animals that had been pushed to the brink of extinction have seen their numbers surge back. Let’s just hope that rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus doesn’t turn out to have any other side effects.

Australia’s rabbits are far from alone in proving that sometimes we should leave animals and plants where we found them.

Like the Nile perch, a six-foot-long ravenous predator that, as you might guess from the name, comes from the Nile. However, the British colonizers of East Africa had bigger plans for it. They thought it would be a terribly good idea to introduce it into Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa. Lake Victoria already had lots of fish in it, and local fishermen were perfectly content fishing those fish, but the British thought that this situation could be improved. The biggest group of fish in the lake at the time were hundreds of different species of cichlids, those small, adorable-looking fish beloved of aquarium keepers. Unfortunately for the cichlids, the British colonial officials hated them, describing them as “trash fish.”

They decided that Lake Victoria would be much better with bigger, cooler fish in it. It would make for superior fishing, they reckoned. Lots of biologists warned them that this was not a great idea, but in 1954 they went ahead and introduced the Nile perch into the lake. The Nile perch then did what Nile perch do: they ate their way through species after species.

The British officials were right about one thing, in that it really did make for superior fishing. The fishing industry boomed, with Nile perch proving immensely popular both as a commercial catch for food and an enjoyable catch for sport. But while the value of the fishing industry shot up by 500 percent, supporting hundreds of thousands of jobs, the number of species in Lake Victoria plummeted. More than 500 other species became extinct, including over 200 species of the poor unfortunate cichlids.

It’s not just animals that can get out of control. Kudzu, a vine common across Asia, was widely introduced into the USA in the 1930s in an attempt to solve a problem that we’ve already mentioned: the Dust Bowl. Officials hoped that the fast-growing vine would help knot the soil back together and prevent further erosion. And it was quite good at that. Unfortunately, it was also quite good at smothering other plants and trees, as well as houses, cars and anything else it came across. It became so widespread across the southern United States that it was given the nickname “the vine that ate the South.”

In fairness to kudzu, it isn’t quite the triffid-like demon plant that some mythology suggests, and recent studies have found it covers less land than commonly thought. Still, there’s an awful lot of it where 80 years ago there wasn’t any of it, and it remains officially listed by the US government as a “noxious weed.”

But now might be the time to start feeling sorry for it, because the invasive species has gained an invasive species of its own. Sometime in 2009, the Japanese kudzu bug managed to make its way across the Pacific, and must have been delighted on landing in Atlanta to discover that there was a load of kudzu already there for it to eat. In the space of three years, it had spread through three states, wiping out as much as a third of the kudzu’s biomass. In case you’re thinking, well, that’s good, kudzu problem solved, it’s unfortunately not quite that simple: kudzu bugs also destroy soy crops, a major source of income in many of the affected states. The accidental solution to one problem might turn out to be a much bigger problem in its own right.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Humans: A Brief History of How We F*cked It All Up» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.