The Royal Society resolved to send an eminent astronomer, Charles Green, to Tahiti, and spared neither effort nor money. But, since it was funding such an expensive expedition, it hardly made sense to use it to make just a single astronomical observation. Green was therefore accompanied by a team of eight other scientists from several disciplines, headed by botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander. The team also included artists assigned to produce drawings of the new lands, plants, animals and peoples that the scientists would no doubt encounter. Equipped with the most advanced scientific instruments that Banks and the Royal Society could buy, the expedition was placed under the command of Captain James Cook, an experienced seaman as well as an accomplished geographer and ethnographer.

The expedition left England in 1768, observed the Venus transit from Tahiti in 1769, reconnoitred several Pacific islands, visited Australia and New Zealand, and returned to England in 1771. It brought back enormous quantities of astronomical, geographical, meteorological, botanical, zoological and anthropological data. Its findings made major contributions to a number of disciplines, sparked the imagination of Europeans with astonishing tales of the South Pacific, and inspired future generations of naturalists and astronomers.

One of the fields that benefited from the Cook expedition was medicine. At the time, ships that set sail to distant shores knew that more than half their crew members would die on the journey. The nemesis was not angry natives, enemy warships or homesickness. It was a mysterious ailment called scurvy. Men who came down with the disease grew lethargic and depressed, and their gums and other soft tissues bled. As the disease progressed, their teeth fell out, open sores appeared and they grew feverish, jaundiced, and lost control of their limbs. Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, scurvy is estimated to have claimed the lives of about 2 million sailors. No one knew what caused it, and no matter what remedy was tried, sailors continued to die in droves. The turning point came in 1747, when a British physician, James Lind, conducted a controlled experiment on sailors who suffered from the disease. He separated them into several groups and gave each group a different treatment. One of the test groups was instructed to eat citrus fruits, a common folk remedy for scurvy. The patients in this group promptly recovered. Lind did not know what the citrus fruits had that the sailors’ bodies lacked, but we now know that it is vitamin C. A typical shipboard diet at that time was notably lacking in foods that are rich in this essential nutrient. On long-range voyages sailors usually subsisted on biscuits and beef jerky, and ate almost no fruits or vegetables.

The Royal Navy was not convinced by Lind’s experiments, but James Cook was. He resolved to prove the doctor right. He loaded his boat with a large quantity of sauerkraut and ordered his sailors to eat lots of fresh fruits and vegetables whenever the expedition made landfall. Cook did not lose a single sailor to scurvy. In the following decades, all the world’s navies adopted Cook’s nautical diet, and the lives of countless sailors and passengers were saved. 1

However, the Cook expedition had another, far less benign result. Cook was not only an experienced seaman and geographer, but also a naval officer. The Royal Society financed a large part of the expedition’s expenses, but the ship itself was provided by the Royal Navy. The navy also seconded eighty-five well-armed sailors and marines, and equipped the ship with artillery, muskets, gunpowder and other weaponry. Much of the information collected by the expedition particularly the astronomical, geographical, meteorological and anthropological data – was of obvious political and military value. The discovery of an effective treatment for scurvy greatly contributed to British control of the world’s oceans and its ability to send armies to the other side of the world. Cook claimed for Britain many of the islands and lands he ‘discovered’, most notably Australia. The Cook expedition laid the foundation for the British occupation of the south-western Pacific Ocean; for the conquest of Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand; for the settlement of millions of Europeans in the new colonies; and for the extermination of their native cultures and most of their native populations. 2

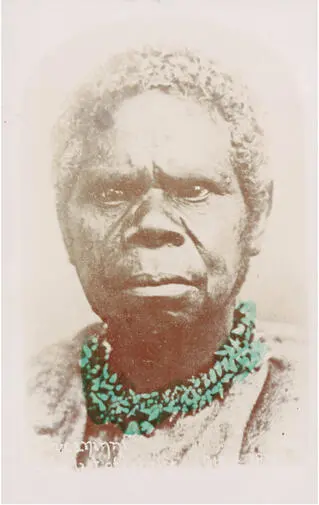

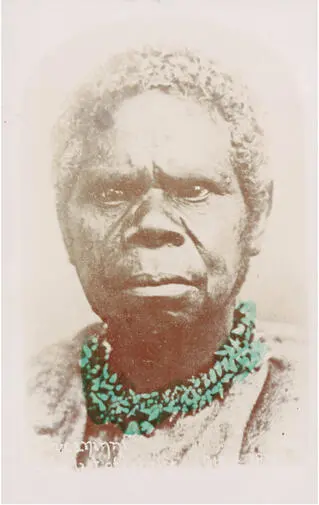

In the century following the Cook expedition, the most fertile lands of Australia and New Zealand were taken from their previous inhabitants by European settlers. The native population dropped by up to 90 per cent and the survivors were subjected to a harsh regime of racial oppression. For the Aborigines of Australia and the Maoris of New Zealand, the Cook expedition was the beginning of a catastrophe from which they have never recovered.

An even worse fate befell the natives of Tasmania. Having survived for 10,000 years in splendid isolation, they were completely wiped out, to the last man, woman and child, within a century of Cook’s arrival. European settlers first drove them off the richest parts of the island, and then, coveting even the remaining wilderness, hunted them down and killed them systematically. The few survivors were hounded into an evangelical concentration camp, where well-meaning but not particularly open-minded missionaries tried to indoctrinate them in the ways of the modern world. The Tasmanians were instructed in reading and writing, Christianity and various ‘productive skills’ such as sewing clothes and farming. But they refused to learn. They became ever more melancholic, stopped having children, lost all interest in life, and finally chose the only escape route from the modern world of science and progress – death.

Alas, science and progress pursued them even to the afterlife. The corpses of the last Tasmanians were seized in the name of science by anthropologists and curators. They were dissected, weighed and measured, and analysed in learned articles. The skulls and skeletons were then put on display in museums and anthropological collections. Only in 1976 did the Tasmanian Museum give up for burial the skeleton of Truganini, the last native Tasmanian, who had died a hundred years earlier. The English Royal College of Surgeons held on to samples of her skin and hair until 2002.

Was Cook’s ship a scientific expedition protected by a military force or a military expedition with a few scientists tagging along? That’s like asking whether your petrol tank is half empty or half full. It was both. The Scientific Revolution and modern imperialism were inseparable. People such as Captain James Cook and the botanist Joseph Banks could hardly distinguish science from empire. Nor could luckless Truganini.

Why Europe?

The fact that people from a large island in the northern Atlantic conquered a large island south of Australia is one of history’s more bizarre occurrences. Not long before Cook’s expedition, the British Isles and western Europe in general were but distant backwaters of the Mediterranean world. Little of importance ever happened there. Even the Roman Empire – the only important premodern European empire – derived most of its wealth from its North African, Balkan and Middle Eastern provinces. Rome’s western European provinces were a poor Wild West, which contributed little aside from minerals and slaves. Northern Europe was so desolate and barbarous that it wasn’t even worth conquering.

35. Truganini, the last native Tasmanian.

Only at the end of the fifteenth century did Europe become a hothouse of important military, political, economic and cultural developments. Between 1500 and 1750, western Europe gained momentum and became master of the ‘Outer World’, meaning the two American continents and the oceans. Yet even then Europe was no match for the great powers of Asia. Europeans managed to conquer America and gain supremacy at sea mainly because the Asiatic powers showed little interest in them. The early modern era was a golden age for the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean, the Safavid Empire in Persia, the Mughal Empire in India, and the Chinese Ming and Qing dynasties. They expanded their territories significantly and enjoyed unprecedented demographic and economic growth. In 1775 Asia accounted for 80 per cent of the world economy. The combined economies of India and China alone represented two-thirds of global production. In comparison, Europe was an economic dwarf. 3

Читать дальше

![Юваль Ной Харари - Sapiens. Краткая история человечества [litres]](/books/34310/yuval-noj-harari-sapiens-kratkaya-istoriya-cheloveche-thumb.webp)

![Юваль Ной Харари - 21 урок для XXI века [Версия с комментированными отличиями перевода]](/books/412481/yuval-noj-harari-21-urok-dlya-xxi-veka-versiya-s-ko-thumb.webp)