The historical process that led to Alamogordo and to the moon is known as the Scientific Revolution. During this revolution humankind has obtained enormous new powers by investing resources in scientific research. It is a revolution because, until about AD 1500, humans the world over doubted their ability to obtain new medical, military and economic powers. While government and wealthy patrons allocated funds to education and scholarship, the aim was, in general, to preserve existing capabilities rather than acquire new ones. The typical premodern ruler gave money to priests, philosophers and poets in the hope that they would legitimise his rule and maintain the social order. He did not expect them to discover new medications, invent new weapons or stimulate economic growth.

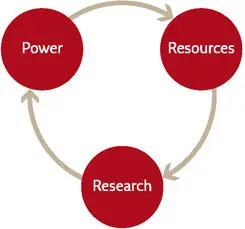

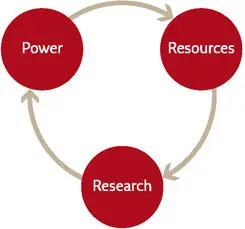

During the last five centuries, humans increasingly came to believe that they could increase their capabilities by investing in scientific research. This wasn’t just blind faith – it was repeatedly proven empirically. The more proofs there were, the more resources wealthy people and governments were willing to put into science. We would never have been able to walk on the moon, engineer microorganisms and split the atom without such investments. The US government, for example, has in recent decades allocated billions of dollars to the study of nuclear physics. The knowledge produced by this research has made possible the construction of nuclear power stations, which provide cheap electricity for American industries, which pay taxes to the US government, which uses some of these taxes to finance further research in nuclear physics.

The Scientific Revolution’s feedback loop. Science needs more than just research to make progress. It depends on the mutual reinforcement of science, politics and economics. Political and economic institutions provide the resources without which scientific research is almost impossible. In return, scientific research provides new powers that are used, among other things, to obtain new resources, some of which are reinvested in research.

Why did modern humans develop a growing belief in their ability to obtain new powers through research? What forged the bond between science, politics and economics? This chapter looks at the unique nature of modern science in order to provide part of the answer. The next two chapters examine the formation of the alliance between science, the European empires and the economics of capitalism.

Ignoramus

Humans have sought to understand the universe at least since the Cognitive Revolution. Our ancestors put a great deal of time and effort into trying to discover the rules that govern the natural world. But modern science differs from all previous traditions of knowledge in three critical ways:

a. The willingness to admit ignorance. Modern science is based on the Latin injunction ignoramus – ‘we do not know’. It assumes that we don’t know everything. Even more critically, it accepts that the things that we think we know could be proven wrong as we gain more knowledge. No concept, idea or theory is sacred and beyond challenge.

b. The centrality of observation and mathematics. Having admitted ignorance, modern science aims to obtain new knowledge. It does so by gathering observations and then using mathematical tools to connect these observations into comprehensive theories.

c. The acquisition of new powers. Modern science is not content with creating theories. It uses these theories in order to acquire new powers, and in particular to develop new technologies.

The Scientific Revolution has not been a revolution of knowledge. It has been above all a revolution of ignorance. The great discovery that launched the Scientific Revolution was the discovery that humans do not know the answers to their most important questions.

Premodern traditions of knowledge such as Islam, Christianity, Buddhism and Confucianism asserted that everything that is important to know about the world was already known. The great gods, or the one almighty God, or the wise people of the past possessed all-encompassing wisdom, which they revealed to us in scriptures and oral traditions. Ordinary mortals gained knowledge by delving into these ancient texts and traditions and understanding them properly. It was inconceivable that the Bible, the Qur’an or the Vedas were missing out on a crucial secret of the universe – a secret that might yet be discovered by flesh-and-blood creatures.

Ancient traditions of knowledge admitted only two kinds of ignorance. First, an individual might be ignorant of something important. To obtain the necessary knowledge, all he needed to do was ask somebody wiser. There was no need to discover something that nobody yet knew. For example, if a peasant in some thirteenth-century Yorkshire village wanted to know how the human race originated, he assumed that Christian tradition held the definitive answer. All he had to do was ask the local priest.

Second, an entire tradition might be ignorant of unimportant things. By definition, whatever the great gods or the wise people of the past did not bother to tell us was unimportant. For example, if our Yorkshire peasant wanted to know how spiders weave their webs, it was pointless to ask the priest, because there was no answer to this question in any of the Christian Scriptures. That did not mean, however, that Christianity was deficient. Rather, it meant that understanding how spiders weave their webs was unimportant. After all, God knew perfectly well how spiders do it. If this were a vital piece of information, necessary for human prosperity and salvation, God would have included a comprehensive explanation in the Bible.

Christianity did not forbid people to study spiders. But spider scholars – if there were any in medieval Europe – had to accept their peripheral role in society and the irrelevance of their findings to the eternal truths of Christianity. No matter what a scholar might discover about spiders or butterflies or Galapagos finches, that knowledge was little more than trivia, with no bearing on the fundamental truths of society, politics and economics.

In fact, things were never quite that simple. In every age, even the most pious and conservative, there were people who argued that there were important things of which their entire tradition was ignorant. Yet such people were usually marginalised or persecuted – or else they founded a new tradition and began arguing that they knew everything there is to know. For example, the prophet Muhammad began his religious career by condemning his fellow Arabs for living in ignorance of the divine truth. Yet Muhammad himself very quickly began to argue that he knew the full truth, and his followers began calling him ‘The Seal of the Prophets’. Henceforth, there was no need of revelations beyond those given to Muhammad.

Modern-day science is a unique tradition of knowledge, inasmuch as it openly admits collective ignorance regarding the most important questions . Darwin never argued that he was ‘The Seal of the Biologists’, and that he had solved the riddle of life once and for all. After centuries of extensive scientific research, biologists admit that they still don’t have any good explanation for how brains produce consciousness. Physicists admit that they don’t know what caused the Big Bang, or how to reconcile quantum mechanics with the theory of general relativity.

In other cases, competing scientific theories are vociferously debated on the basis of constantly emerging new evidence. A prime example is the debates about how best to run the economy. Though individual economists may claim that their method is the best, orthodoxy changes with every financial crisis and stock-exchange bubble, and it is generally accepted that the final word on economics is yet to be said.

Читать дальше

![Юваль Ной Харари - Sapiens. Краткая история человечества [litres]](/books/34310/yuval-noj-harari-sapiens-kratkaya-istoriya-cheloveche-thumb.webp)

![Юваль Ной Харари - 21 урок для XXI века [Версия с комментированными отличиями перевода]](/books/412481/yuval-noj-harari-21-urok-dlya-xxi-veka-versiya-s-ko-thumb.webp)