The religious wars between Catholics and Protestants that swept Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are particularly notorious. All those involved accepted Christ’s divinity and His gospel of compassion and love. However, they disagreed about the nature of this love. Protestants believed that the divine love is so great that God was incarnated in flesh and allowed Himself to be tortured and crucified, thereby redeeming the original sin and opening the gates of heaven to all those who professed faith in Him. Catholics maintained that faith, while essential, was not enough. To enter heaven, believers had to participate in church rituals and do good deeds. Protestants refused to accept this, arguing that this quid pro quo belittles God’s greatness and love. Whoever thinks that entry to heaven depends upon his or her own good deeds magnifies his own importance, and implies that Christ’s suffering on the cross and God’s love for humankind are not enough.

These theological disputes turned so violent that during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Catholics and Protestants killed each other by the hundreds of thousands. On 23 August 1572, French Catholics who stressed the importance of good deeds attacked communities of French Protestants who highlighted God’s love for humankind. In this attack, the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, between 5,000 and 10,000 Protestants were slaughtered in less than twenty-four hours. When the pope in Rome heard the news from France, he was so overcome by joy that he organised festive prayers to celebrate the occasion and commissioned Giorgio Vasari to decorate one of the Vatican’s rooms with a fresco of the massacre (the room is currently off-limits to visitors). 2More Christians were killed by fellow Christians in those twenty-four hours than by the polytheistic Roman Empire throughout its entire existence.

God is One

With time some followers of polytheist gods became so fond of their particular patron that they drifted away from the basic polytheist insight. They began to believe that their god was the only god, and that He was in fact the supreme power of the universe. Yet at the same time they continued to view Him as possessing interests and biases, and believed that they could strike deals with Him. Thus were born monotheist religions, whose followers beseech the supreme power of the universe to help them recover from illness, win the lottery and gain victory in war.

The first monotheist religion known to us appeared in Egypt, c .350 BC, when Pharaoh Akhenaten declared that one of the minor deities of the Egyptian pantheon, the god Aten, was, in fact, the supreme power ruling the universe. Akhenaten institutionalised the worship of Aten as the state religion and tried to check the worship of all other gods. His religious revolution, however, was unsuccessful. After his death, the worship of Aten was abandoned in favour of the old pantheon.

Polytheism continued to give birth here and there to other monotheist religions, but they remained marginal, not least because they failed to digest their own universal message. Judaism, for example, argued that the supreme power of the universe has interests and biases, yet His chief interest is in the tiny Jewish nation and in the obscure land of Israel. Judaism had little to offer other nations, and throughout most of its existence it has not been a missionary religion. This stage can be called the stage of ‘local monotheism’.

The big breakthrough came with Christianity. This faith began as an esoteric Jewish sect that sought to convince Jews that Jesus of Nazareth was their long-awaited messiah. However, one of the sect’s first leaders, Paul of Tarsus, reasoned that if the supreme power of the universe has interests and biases, and if He had bothered to incarnate Himself in the flesh and to die on the cross for the salvation of humankind, then this is something everyone should hear about, not just Jews. It was thus necessary to spread the good word – the gospel – about Jesus throughout the world.

Paul’s arguments fell on fertile ground. Christians began organising widespread missionary activities aimed at all humans. In one of history’s strangest twists, this esoteric Jewish sect took over the mighty Roman Empire.

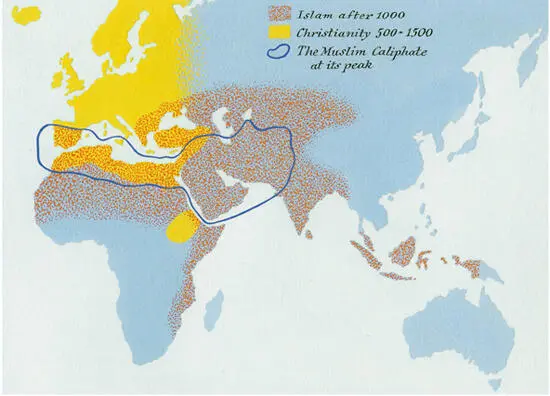

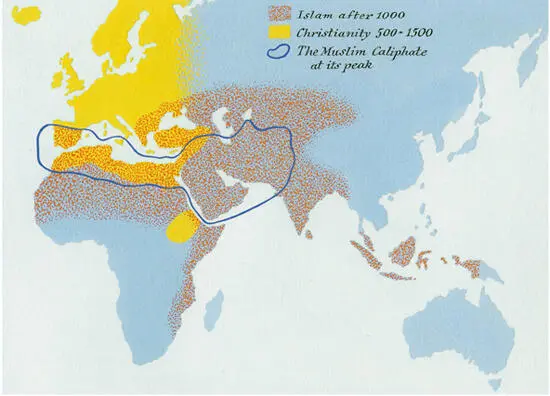

Christian success served as a model for another monotheist religion that appeared in the Arabian peninsula in the seventh century – Islam. Like Christianity, Islam, too, began as a small sect in a remote corner of the world, but in an even stranger and swifter historical surprise it managed to break out of the deserts of Arabia and conquer an immense empire stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to India. Henceforth, the monotheist idea played a central role in world history.

Monotheists have tended to be far more fanatical and missionary than polytheists. A religion that recognises the legitimacy of other faiths implies either that its god is not the supreme power of the universe, or that it received from God just part of the universal truth. Since monotheists have usually believed that they are in possession of the entire message of the one and only God, they have been compelled to discredit all other religions. Over the last two millennia, monotheists repeatedly tried to strengthen their hand by violently exterminating all competition.

It worked. At the beginning of the first century AD, there were hardly any monotheists in the world. Around AD 500, one of the world’s largest empires – the Roman Empire – was a Christian polity, and missionaries were busy spreading Christianity to other parts of Europe, Asia and Africa. By the end of the first millennium AD, most people in Europe, West Asia and North Africa were monotheists, and empires from the Atlantic Ocean to the Himalayas claimed to be ordained by the single great God. By the early sixteenth century, monotheism dominated most of Afro-Asia, with the exception of East Asia and the southern parts of Africa, and it began extending long tentacles towards South Africa, America and Oceania. Today most people outside East Asia adhere to one monotheist religion or another, and the global political order is built on monotheistic foundations.

Yet just as animism continued to survive within polytheism, so polytheism continued to survive within monotheism. In theory, once a person believes that the supreme power of the universe has interests and biases, what’s the point in worshipping partial powers? Who would want to approach a lowly bureaucrat when the president’s office is open to you? Indeed, monotheist theology tends to deny the existence of all gods except the supreme God, and to pour hellfire and brimstone over anyone who dares worship them.

Map 5. The Spread of Christianity and Islam.

Yet there has always been a chasm between theological theories and historical realities. Most people have found it difficult to digest the monotheist idea fully. They have continued to divide the world into ‘we’ and ‘they’, and to see the supreme power of the universe as too distant and alien for their mundane needs. The monotheist religions expelled the gods through the front door with a lot of fanfare, only to take them back in through the side window. Christianity, for example, developed its own pantheon of saints, whose cults differed little from those of the polytheistic gods.

Just as the god Jupiter defended Rome and Huitzilopochtli protected the Aztec Empire, so every Christian kingdom had its own patron saint who helped it overcome difficulties and win wars. England was protected by St George, Scotland by St Andrew, Hungary by St Stephen, and France had St Martin. Cities and towns, professions, and even diseases – each had their own saint. The city of Milan had St Ambrose, while St Mark watched over Venice. St Florian protected chimney cleaners, whereas St Mathew lent a hand to tax collectors in distress. If you suffered from headaches you had to pray to St Agathius, but if from toothaches, then St Apollonia was a much better audience.

Читать дальше

![Юваль Ной Харари - Sapiens. Краткая история человечества [litres]](/books/34310/yuval-noj-harari-sapiens-kratkaya-istoriya-cheloveche-thumb.webp)

![Юваль Ной Харари - 21 урок для XXI века [Версия с комментированными отличиями перевода]](/books/412481/yuval-noj-harari-21-urok-dlya-xxi-veka-versiya-s-ko-thumb.webp)