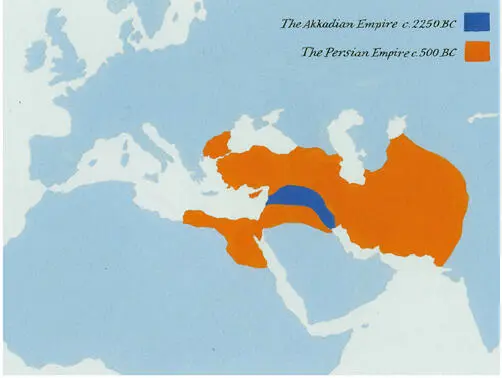

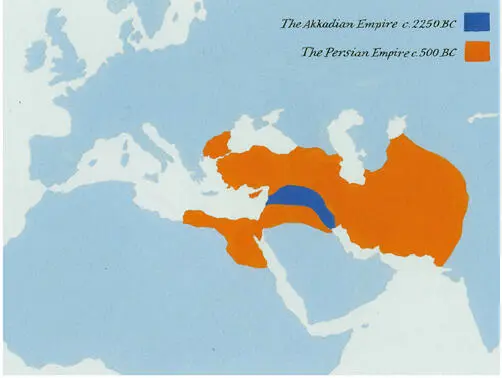

The Akkadian Empire did not last long after its founder’s death, but Sargon left behind an imperial mantle that seldom remained unclaimed. For the next 1,700 years, Assyrian, Babylonian and Hittite kings adopted Sargon as a role model, boasting that they, too, had conquered the entire world. Then, around 550 BC, Cyrus the Great of Persia came along with an even more impressive boast.

Map 4. The Akkadian Empire and the Persian Empire.

The kings of Assyria always remained the kings of Assyria. Even when they claimed to rule the entire world, it was obvious that they were doing it for the greater glory of Assyria, and they were not apologetic about it. Cyrus, on the other hand, claimed not merely to rule the whole world, but to do so for the sake of all people. ‘We are conquering you for your own benefit,’ said the Persians. Cyrus wanted the peoples he subjected to love him and to count themselves lucky to be Persian vassals. The most famous example of Cyrus’ innovative efforts to gain the approbation of a nation living under the thumb of his empire was his command that the Jewish exiles in Babylonia be allowed to return to their Judaean homeland and rebuild their temple. He even offered them financial assistance. Cyrus did not see himself as a Persian king ruling over Jews – he was also the king of the Jews, and thus responsible for their welfare.

The presumption to rule the entire world for the benefit of all its inhabitants was startling. Evolution has made Homo sapiens , like other social mammals, a xenophobic creature. Sapiens instinctively divide humanity into two parts, ‘we’ and ‘they’. We are people like you and me, who share our language, religion and customs. We are all responsible for each other, but not responsible for them. We were always distinct from them, and owe them nothing. We don’t want to see any of them in our territory, and we don’t care an iota what happens in their territory. They are barely even human. In the language of the Dinka people of the Sudan, ‘Dinka’ simply means ‘people’. People who are not Dinka are not people. The Dinka’s bitter enemies are the Nuer. What does the word Nuer mean in Nuer language? It means ‘original people’. Thousands of kilometres from the Sudan deserts, in the frozen ice-lands of Alaska and north-eastern Siberia, live the Yupiks. What does Yupik mean in Yupik language? It means ‘real people’. 3

In contrast with this ethnic exclusiveness, imperial ideology from Cyrus onward has tended to be inclusive and all-encompassing. Even though it has often emphasised racial and cultural differences between rulers and ruled, it has still recognised the basic unity of the entire world, the existence of a single set of principles governing all places and times, and the mutual responsibilities of all human beings. Humankind is seen as a large family: the privileges of the parents go hand in hand with responsibility for the welfare of the children.

This new imperial vision passed from Cyrus and the Persians to Alexander the Great, and from him to Hellenistic kings, Roman emperors, Muslim caliphs, Indian dynasts, and eventually even to Soviet premiers and American presidents. This benevolent imperial vision has justified the existence of empires, and negated not only attempts by subject peoples to rebel, but also attempts by independent peoples to resist imperial expansion.

Similar imperial visions were developed independently of the Persian model in other parts of the world, most notably in Central America, in the Andean region, and in China. According to traditional Chinese political theory, Heaven ( Tian ) is the source of all legitimate authority on earth. Heaven chooses the most worthy person or family and gives them the Mandate of Heaven. This person or family then rules over All Under Heaven ( Tianxia ) for the benefit of all its inhabitants. Thus, a legitimate authority is – by definition – universal. If a ruler lacks the Mandate of Heaven, then he lacks legitimacy to rule even a single city. If a ruler enjoys the mandate, he is obliged to spread justice and harmony to the entire world. The Mandate of Heaven could not be given to several candidates simultaneously, and consequently one could not legitimise the existence of more than one independent state.

The first emperor of the united Chinese empire, Qín Shǐ Huángdì, boasted that ‘throughout the six directions [of the universe] everything belongs to the emperor … wherever there is a human footprint, there is not one who did not become a subject [of the emperor] … his kindness reaches even oxen and horses. There is not one who did not benefit. Every man is safe under his own roof.’ 4In Chinese political thinking as well as Chinese historical memory, imperial periods were henceforth seen as golden ages of order and justice. In contradiction to the modern Western view that a just world is composed of separate nation states, in China periods of political fragmentation were seen as dark ages of chaos and injustice. This perception has had far-reaching implications for Chinese history. Every time an empire collapsed, the dominant political theory goaded the powers that be not to settle for paltry independent principalities, but to attempt reunification. Sooner or later these attempts always succeeded.

When They Become Us

Empires have played a decisive part in amalgamating many small cultures into fewer big cultures. Ideas, people, goods and technology spread more easily within the borders of an empire than in a politically fragmented region. Often enough, it was the empires themselves which deliberately spread ideas, institutions, customs and norms. One reason was to make life easier for themselves. It is difficult to rule an empire in which every little district has its own set of laws, its own form of writing, its own language and its own money. Standardisation was a boon to emperors.

A second and equally important reason why empires actively spread a common culture was to gain legitimacy. At least since the days of Cyrus and Qín Shǐ Huángdì, empires have justified their actions – whether road-building or bloodshed – as necessary to spread a superior culture from which the conquered benefit even more than the conquerors.

The benefits were sometimes salient – law enforcement, urban planning, standardisation of weights and measures – and sometimes questionable – taxes, conscription, emperor worship. But most imperial elites earnestly believed that they were working for the general welfare of all the empires inhabitants. China’s ruling class treated their country’s neighbours and its foreign subjects as miserable barbarians to whom the empire must bring the benefits of culture. The Mandate of Heaven was bestowed upon the emperor not in order to exploit the world, but in order to educate humanity. The Romans, too, justified their dominion by arguing that they were endowing the barbarians with peace, justice and refinement. The wild Germans and painted Gauls had lived in squalor and ignorance until the Romans tamed them with law, cleaned them up in public bathhouses, and improved them with philosophy. The Mauryan Empire in the third century BC took as its mission the dissemination of Buddha’s teachings to an ignorant world. The Muslim caliphs received a divine mandate to spread the Prophet’s revelation, peacefully if possible but by the sword if necessary. The Spanish and Portuguese empires proclaimed that it was not riches they sought in the Indies and America, but converts to the true faith. The sun never set on the British mission to spread the twin gospels of liberalism and free trade. The Soviets felt duty-bound to facilitate the inexorable historical march from capitalism towards the utopian dictatorship of the proletariat. Many Americans nowadays maintain that their government has a moral imperative to bring Third World countries the benefits of democracy and human rights, even if these goods are delivered by cruise missiles and F-16s.

Читать дальше

![Юваль Ной Харари - Sapiens. Краткая история человечества [litres]](/books/34310/yuval-noj-harari-sapiens-kratkaya-istoriya-cheloveche-thumb.webp)

![Юваль Ной Харари - 21 урок для XXI века [Версия с комментированными отличиями перевода]](/books/412481/yuval-noj-harari-21-urok-dlya-xxi-veka-versiya-s-ko-thumb.webp)