Chanel didn’t face a judge or jury until 1946, when Judge Serre and his team put together documents that tied Chanel and her codename of ‘Westminster’ to the Nazis. They were unable to find any documented proof of information, or tangible advantages that Chanel had actually achieved for the Nazi party, so they were unable to issue an immediate warrant for her arrest. They did, however, issue a bench warrant for her to appear and explain herself and her extensive involvement and connections with the Germans. Judge Roger Serre issued a warrant on 16 April 1946, demanding that the police and the French border patrols bring her in to answer for the claims made by Baron Vaufreland when he was being interrogated. Chanel wouldn’t appear in court for years, and not in front of Judge Serre.

Chanel finally answered the call a few years later to explain her actions during the war and about her connection to known Nazi conspirator and French traitor Baron Louis de Vaufreland. It turns out that in some of her travels she was paired with the Baron. Vaufreland bore the tag ‘V-Mann’ in his Abwehr files, which indicated that he had the trust of the Gestapo. The job that Vaufreland undertook was primarily recruitment of men and women who could be convinced or coerced into becoming spies for the Nazis. Apparently, Chanel would travel along with Vaufreland, in order to help conceal his actions. Vaufreland faced trial on 12 July 1949 for crimes against the French people by aiding the enemy during wartime. Coco Chanel was brought to testify during the trial and while she admitted to knowing Vaufreland, she downplayed their association and denied any wrong-doing. The prosecuting attorney, fixated on Vaufreland rather than Chanel, didn’t press her very hard during her testimony. She then returned to her safe haven in Switzerland, while Vaufreland was found guilty and sentenced to six years in prison.

Biographer Hal Vaughn speculated in his book, Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War, that Chanel might have paid off a former Nazi after the war. According to Vaughn, when former Nazi SS head of foreign intelligence, Walter Schellenberg, was looking to release his memoirs, and in an effort to suppress the book, Chanel paid him and his family off. Schellenberg, of course, had intimate knowledge of Chanel’s involvement with the Nazis.

Later In Life

Coco Chanel had the luxury of living out the rest of her life in freedom, having never been truly taken to task for her actions during the war. She remained successful and outspoken, giving several interviews over the years that would contradict each other about various events in her life. On 10 January 1971, Chanel died in the Hotel Ritz, the lavish home she enjoyed during the Nazi occupation of Paris. She was 87 years old.

The Chanel Brand Today

When Hal Vaughn’s salacious book, Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War , outright accused Coco of being a Nazi spy, the Chanel fashion house decided to reply in a press release. A representative for the fashion house said the following:

What’s certain is that she had a relationship with a German aristocrat during the War. Clearly it wasn’t the best period to have a love story with a German even if Baron von Dincklage was English by his mother and she (Chanel) knew him before the War.

On the subject of Coco Chanel being perceived as an anti-Semite, the House of Chanel has said the following:

She would hardly have formed a relationship with the family of the owners or counted Jewish people among her close friends and professional partners such as the Rothschild family, the photographer Irving Penn or the well-known French writer Joseph Kessel had these really been her views.

Chapter Six

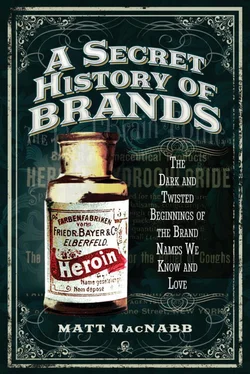

Bayer: Heroin and Genocide

The history of Bayer is one that can only be described as complex and troubled. We’ve all heard of heroin, one of the most dangerous and addictive drugs in the world. The very mention of heroin can inspire images of underweight junkies, needles, and arms covered in track marks. The reality of heroin is that it causes an immense amount of suffering for the users and their loved ones. What you may not think about when you picture heroin is a bottle of the drug on a store shelf. Imagine heroin bottled by Bayer, the makers of aspirin, and marketed as a cough remedy for children. This was the reality a little over a century ago. Then, imagine for a moment that the creation and introduction of heroin was only a drop in the bucket, as the same company would be a co-sponsor of the Nazi concentration camps during the Second World War.

An Early History of Opioids

The origins of opium date as far back as 3400 BCE in the ancient region of Mesopotamia. The opium poppy was also found referenced in ancient texts from Egyptian, Sanskrit, Greek, Minoan and Sumerian cultures. The Sumerians would refer to it as the aptly named ‘hul gil’, which means ‘plant of joy’. During the nineteenth century, when the Wild West of America was being settled and the railroad was under construction, a lot of immigrant workers were imported from China. These Chinese labourers brought with them opium, a substance that would catch on like wildfire. The images we see projected on film of a cowboy at the saloon drinking whiskey may have been a common sight in the movies and on television, but it was perhaps even more common in real life to find legendary characters like Wild Bill Hickock in a dimly lit opium den, high out of his mind.

The next stage in the story of opium was morphine. Originally named morphium, for the Greek god Morpheus (the god of dreams), the alkaloid that would become morphine was first isolated from the opium poppy by pharmacist’s apprentice Friedrich Sertürner sometime between 1803 and 1805. It was the very first time any alkaloid had been isolated from a plant. Morphine was later introduced to the marketplace for consumption by Merck in 1827. It was the shortcomings in morphine that would lead to the creation of heroin.

Medicine vs Snake Oils

You’ve no doubt heard the term ‘snake oil’ or ‘snake oil salesman’, at least in passing. While it’s a cliché for a hoax nowadays, these elixirs were a very real and commonly used cure-all remedy throughout the 1700s and 1800s. The Victorian era was rife with quack medicine that made all sorts of claims, none of which needed to be proved by any government regulation until 1858 in the United Kingdom, and after the turn of the twentieth century in the United States.

When we think about snake oil today, what often comes to mind is a placebo or a hoax medicine that doesn’t actually work. That wasn’t necessarily always the case. While we didn’t have a lot of the established medicines in the nineteenth century that we have now, many of the remedies that were used did have a medical basis. Bayer would initially market their heroin product like snake oil, which will be explored later in this chapter.

A few of the more famous, or rather infamous, snake oils were ‘Richard Stoughton’s elixir’, ‘Worner’s Famous Rattlesnake Oil’ and ‘Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil’. Richard Stoughton’s elixir was one of the first bitters to receive a patent in England, back in 1712. The ingredients are said to have included the rinds of oranges, an ounce of gentian scraped and sliced, a sixpenny worth of cochineal and a pint of brandy. Gentian was often used for flavouring various bitters and is said to assist with digestive issues. The cochineal was most likely used to dye the mixture. Worner’s Famous Rattlesnake Oil was said to cure rheumatism, paralysis, stiff joints, contracted cords and muscles, lumbago, pneumonia, neuralgia, deafness, asthma and catarrh. The claims made by Worner were clearly absurd and unfounded.

Читать дальше