To be frank, science knows surprisingly little about mind and consciousness. Current orthodoxy holds that consciousness is created by electrochemical reactions in the brain, and that mental experiences fulfil some essential data-processing function. 3However, nobody has any idea how a congeries of biochemical reactions and electrical currents in the brain creates the subjective experience of pain, anger or love. Perhaps we will have a solid explanation in ten or fifty years. But as of 2016, we have no such explanation, and we had better be clear about that.

Using fMRI scans, implanted electrodes and other sophisticated gadgets, scientists have certainly identified correlations and even causal links between electrical currents in the brain and various subjective experiences. Just by looking at brain activity, scientists can know whether you are awake, dreaming or in deep sleep. They can briefly flash an image in front of your eyes, just at the threshold of conscious perception, and determine (without asking you) whether you have become aware of the image or not. They have even managed to link individual brain neurons with specific mental content, discovering for example a ‘Bill Clinton’ neuron and a ‘Homer Simpson’ neuron. When the ‘Bill Clinton’ neuron is on, the person is thinking of the forty-second president of the USA; show the person an image of Homer Simpson, and the eponymous neuron is bound to ignite.

More broadly, scientists know that if an electric storm arises in a given brain area, you probably feel angry. If this storm subsides and a different area lights up – you are experiencing love. Indeed, scientists can even induce feelings of anger or love by electrically stimulating the right neurons. But how on earth does the movement of electrons from one place to the other translate into a subjective image of Bill Clinton, or a subjective feeling of anger or love?

The most common explanation points out that the brain is a highly complex system, with more than 80 billion neurons connected into numerous intricate webs. When billions of neurons send billions of electric signals back and forth, subjective experiences emerge. Even though the sending and receiving of each electric signal is a simple biochemical phenomenon, the interaction among all these signals creates something far more complex – the stream of consciousness. We observe the same dynamic in many other fields. The movement of a single car is a simple action, but when millions of cars move and interact simultaneously, traffic jams emerge. The buying and selling of a single share is simple enough, but when millions of traders buy and sell millions of shares it can lead to economic crises that dumbfound even the experts.

Yet this explanation explains nothing. It merely affirms that the problem is very complicated. It does not offer any insight into how one kind of phenomenon (billions of electric signals moving from here to there) creates a very different kind of phenomenon (subjective experiences of anger or love). The analogy to other complex processes such as traffic jams and economic crises is flawed. What creates a traffic jam? If you follow a single car, you will never understand it. The jam results from the interactions among many cars. Car A influences the movement of car B, which blocks the path of car C, and so on. Yet if you map the movements of all the relevant cars, and how each impacts the other, you will get a complete account of the traffic jam. It would be pointless to ask, ‘But how do all these movements create the traffic jam?’ For ‘traffic jam’ is simply the abstract term we humans decided to use for this particular collection of events.

In contrast, ‘anger’ isn’t an abstract term we have decided to use as a shorthand for billions of electric brain signals. Anger is an extremely concrete experience which people were familiar with long before they knew anything about electricity. When I say, ‘I am angry!’ I am pointing to a very tangible feeling. If you describe how a chemical reaction in a neuron results in an electric signal, and how billions of similar reactions result in billions of additional signals, it is still worthwhile to ask, ‘But how do these billions of events come together to create my concrete feeling of anger?’

When thousands of cars slowly edge their way through London, we call that a traffic jam, but it doesn’t create some great Londonian consciousness that hovers high above Piccadilly and says to itself, ‘Blimey, I feel jammed!’ When millions of people sell billions of shares, we call that an economic crisis, but no great Wall Street spirit grumbles, ‘Shit, I feel I am in crisis.’ When trillions of water molecules coalesce in the sky we call that a cloud, but no cloud consciousness emerges to announce, ‘I feel rainy.’ How is it, then, that when billions of electric signals move around in my brain, a mind emerges that feels ‘I am furious!’? As of 2016, we have absolutely no idea.

Hence if this discussion has left you confused and perplexed, you are in very good company. The best scientists too are a long way from deciphering the enigma of mind and consciousness. One of the wonderful things about science is that when scientists don’t know something, they can try out all kinds of theories and conjunctures, but in the end they can just admit their ignorance.

The Equation of Life

Scientists don’t know how a collection of electric brain signals creates subjective experiences. Even more crucially, they don’t know what could be the evolutionary benefit of such a phenomenon. It is the greatest lacuna in our understanding of life. Humans have feet, because for millions of generations feet enabled our ancestors to chase rabbits and escape lions. Humans have eyes, because for countless millennia eyes enabled our forebears to see whither the rabbit was heading and whence the lion was coming. But why do humans have subjective experiences of hunger and fear?

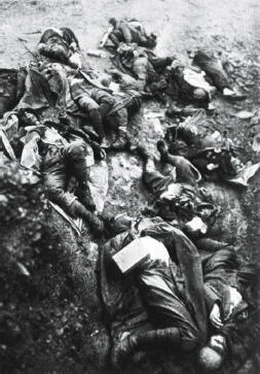

Not long ago, biologists gave a very simple answer. Subjective experiences are essential for our survival, because if we didn’t feel hunger or fear we would not have bothered to chase rabbits and flee lions. Upon seeing a lion, why did a man flee? Well, he was frightened, so he ran away. Subjective experiences explained human actions. Yet today scientists provide a much more detailed explanation. When a man sees a lion, electric signals move from the eye to the brain. The incoming signals stimulate certain neurons, which react by firing off more signals. These stimulate other neurons down the line, which fire in their turn. If enough of the right neurons fire at a sufficiently rapid rate, commands are sent to the adrenal glands to flood the body with adrenaline, the heart is instructed to beat faster, while neurons in the motor centre send signals down to the leg muscles, which begin to stretch and contract, and the man runs away from the lion.

Ironically, the better we map this process, the harder it becomes to explain conscious feelings. The better we understand the brain, the more redundant the mind seems. If the entire system works by electric signals passing from here to there, why the hell do we also need to feel fear? If a chain of electrochemical reactions leads all the way from the nerve cells in the eye to the movements of leg muscles, why add subjective experiences to this chain? What do they do? Countless domino pieces can fall one after the other without any need of subjective experiences. Why do neurons need feelings in order to stimulate one another, or in order to tell the adrenal gland to start pumping? Indeed, 99 per cent of bodily activities, including muscle movement and hormonal secretions, take place without any need of conscious feelings. So why do the neurons, muscles and glands need such feelings in the remaining 1 per cent of cases?

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу