The human eye, for example, is an extremely complex system made of numerous smaller parts such as the lens, the cornea and the retina. The eye did not pop out of nowhere complete with all these components. Rather, it evolved step by tiny step through millions of years. Our eye is very similar to the eye of Homo erectus, who lived 1 million years ago. It is somewhat less similar to the eye of Australopithecus, who lived 5 million years ago. It is very different from the eye of Dryolestes, who lived 150 million years ago. And it seems to have nothing in common with the unicellular organisms that inhabited our planet hundreds of millions of years ago.

Yet even unicellular organisms have tiny organelles that enable the microorganism to distinguish light from darkness, and move towards one or the other. The path leading from such archaic sensors to the human eye is long and winding, but if you have hundreds of millions of years to spare, you can certainly cover the entire path, step by step. You can do that because the eye is composed of many different parts. If every few generations a small mutation slightly changes one of these parts – say, the cornea becomes a bit more curved – after millions of generations these changes can result in a human eye. If the eye were a holistic entity, devoid of any parts, it could never have evolved by natural selection.

That’s why the theory of evolution cannot accept the idea of souls, at least if by ‘soul’ we mean something indivisible, immutable and potentially eternal. Such an entity cannot possibly result from a step-by-step evolution. Natural selection could produce a human eye, because the eye has parts. But the soul has no parts. If the Sapiens soul evolved step by step from the Erectus soul, what exactly were these steps? Is there some part of the soul that is more developed in Sapiens than in Erectus? But the soul has no parts.

You might argue that human souls did not evolve, but appeared one bright day in the fullness of their glory. But when exactly was that bright day? When we look closely at the evolution of humankind, it is embarrassingly difficult to find it. Every human that ever existed came into being as a result of male sperm inseminating a female egg. Think of the first baby to possess a soul. That baby was very similar to her mother and father, except that she had a soul and they didn’t. Our biological knowledge can certainly explain the birth of a baby whose cornea was a bit more curved than her parents’ corneas. A slight mutation in a single gene can account for that. But biology cannot explain the birth of a baby possessing an eternal soul from parents who did not have even a shred of a soul. Is a single mutation, or even several mutations, enough to give an animal an essence secure against all changes, including even death?

Hence the existence of souls cannot be squared with the theory of evolution. Evolution means change, and is incapable of producing everlasting entities. From an evolutionary perspective, the closest thing we have to a human essence is our DNA, and the DNA molecule is the vehicle of mutation rather than the seat of eternity. This terrifies large numbers of people, who prefer to reject the theory of evolution rather than give up their souls.

Why the Stock Exchange Has No Consciousness

Another story employed to justify human superiority says that of all the animals on earth, only Homo sapiens has a conscious mind. Mind is something very different from soul. The mind isn’t some mystical eternal entity. Nor is it an organ such as the eye or the brain. Rather, the mind is a flow of subjective experiences, such as pain, pleasure, anger and love. These mental experiences are made of interlinked sensations, emotions and thoughts, which flash for a brief moment, and immediately disappear. Then other experiences flicker and vanish, arising for an instant and passing away. (When reflecting on it, we often try to sort the experiences into distinct categories such as sensations, emotions and thoughts, but in actuality they are all mingled together.) This frenzied collection of experiences constitutes the stream of consciousness. Unlike the everlasting soul, the mind has many parts, it constantly changes, and there is no reason to think it is eternal.

The soul is a story that some people accept while others reject. The stream of consciousness, in contrast, is the concrete reality we directly witness every moment. It is the surest thing in the world. You cannot doubt its existence. Even when we are consumed by doubt and ask ourselves: ‘Do subjective experiences really exist?’ we can be certain that we are experiencing doubt.

What exactly are the conscious experiences that constitute the flow of the mind? Every subjective experience has two fundamental characteristics: sensation and desire. Robots and computers have no consciousness because despite their myriad abilities they feel nothing and crave nothing. A robot may have an energy sensor that signals to its central processing unit when the battery is about to run out. The robot may then move towards an electrical socket, plug itself in and recharge its battery. However, throughout this process the robot doesn’t experience anything. In contrast, a human being depleted of energy feels hunger and craves to stop this unpleasant sensation. That’s why we say that humans are conscious beings and robots aren’t, and why it is a crime to make people work until they collapse from hunger and exhaustion, whereas making robots work until their batteries run out carries no moral opprobrium.

And what about animals? Are they conscious? Do they have subjective experiences? Is it okay to force a horse to work until he collapses from exhaustion? As noted earlier, the life sciences currently argue that all mammals and birds, and at least some reptiles and fish, have sensations and emotions. However, the most up-to-date theories also maintain that sensations and emotions are biochemical data-processing algorithms. Since we know that robots and computers process data without having any subjective experiences, maybe it works the same with animals? Indeed, we know that even in humans many sensory and emotional brain circuits can process data and initiate actions completely unconsciously. So perhaps behind all the sensations and emotions we ascribe to animals – hunger, fear, love and loyalty – lurk only unconscious algorithms rather than subjective experiences? 2

This theory was upheld by the father of modern philosophy, René Descartes. In the seventeenth century Descartes maintained that only humans feel and crave, whereas all other animals are mindless automata, akin to a robot or a vending machine. When a man kicks a dog, the dog experiences nothing. The dog flinches and howls automatically, just like a humming vending machine that makes a cup of coffee without feeling or wanting anything.

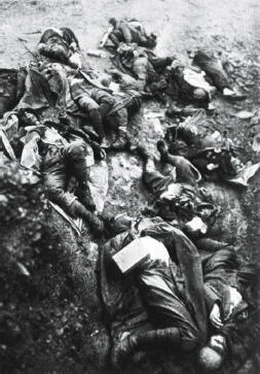

This theory was widely accepted in Descartes’ day. Seventeenth-century doctors and scholars dissected live dogs and observed the working of their internal organs, without either anaesthetics or scruples. They didn’t see anything wrong with that, just as we don’t see anything wrong in opening the lid of a vending machine and observing its gears and conveyors. In the early twenty-first century there are still plenty of people who argue that animals have no consciousness, or at most, that they have a very different and inferior type of consciousness.

In order to decide whether animals have conscious minds similar to our own, we must first get a better understanding of how minds function, and what role they play. These are extremely difficult questions, but it is worthwhile to devote some time to them, because the mind will be the hero of several subsequent chapters. We won’t be able to grasp the full implications of novel technologies such as artificial intelligence if we don’t know what minds are. Hence let’s leave aside for a moment the particular question of animal minds, and examine what science knows about minds and consciousness in general. We will focus on examples taken from the study of human consciousness – which is more accessible to us – and later on return to animals and ask whether what’s true of humans is also true of our furry and feathery cousins.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу