About this time Mr. Gladstone succeeded Lord Stanley in England as the Secretary of State for the Colonies; and as he had shortly afterwards to complain that, in reporting on these and other important matters, Sir Eardley had sent home vague statements for the purpose of deceiving the Imperial authorities, the Governor was recalled. But he was destined never to leave the scene of his troubles; for, two or three months after his recall, he became ill and died in the colony.

5. Denison and the Transportation Question.—On the arrival of the next Governor, Sir William Denison, in 1847, the Queen reinstated the “Patriotic Six”; and the colonists, encouraged by this concession, vigorously set to work to obtain their two great desires—namely, government by elective parliaments, and the abolition of transportation. It was found that, between the years 1846 and 1850, more than 25,000 convicts had been brought into Tasmania; free immigration had ceased, and the number of convicts in the colony was nearly double the number of free men. In all parts of the world, if it became known that a man had come from Tasmania, he was looked upon with the utmost distrust and suspicion, and was shunned as contaminated. On behalf of the colonists, a gentleman named MʻLachlan went to London for the purpose of laying before Mr. Gladstone the grievances under which they suffered; at the same time, within the colony, Mr. Pitcairn strenuously exerted himself to prepare petitions against transportation, and to forward them to the Imperial authorities. These representations were favourably entertained, and, in a short time, Sir W. Denison received orders to inquire whether it was the unanimous desire of the people of Tasmania that transportation should cease entirely. The question was put to all the magistrates of the colony, who submitted it to the people in public meetings. The discussion was warm, and party feeling ran high. There were some who had been benefited by the trade and the English subsidies which convicts brought to the colony, and there were others who desired, at all hazards, to retain the cheap labour of the liberated convicts. These exerted themselves to maintain the system of transportation; but the great body of the people were determined on its abolition, and the answer returned by every meeting expressed the same unhesitating sentiment—Transportation ought to be abolished entirely. Accordingly, it was not long before the Tasmanians were informed by the Governor that transportation should, in a short time, be discontinued. But Earl Grey was now preparing another scheme for the treatment of convicts: they were to be kept for a time in English prisons; after they had served a part of their sentence, if they had been well conducted, the British Government would take them out to the colonies and land them there as free men, so as to give them a chance of starting an honourable career in a new country. It was a scheme of kind intention for the reformation of criminals that were not utterly bad, while the English Government would keep all the worst prisoners at home under lock and key. But the colonies had no desire to receive even the better half of the prisoners. They were afraid that cunning criminals would sham a great deal of reformation in order to be set free, and would then revert to their former ways whenever they were let loose in the colonies. But Earl Grey was resolved to give the criminal a fair chance. Ships filled with convicts were sent out to the various colonies, but the prisoners were not allowed to land. In 1849 the Randolph appeared at Port Phillip Heads; but the people of Melbourne forbade the captain to enter. He paid no attention to the order, and sailed up the bay to Williamstown. But when he was preparing to land the convicts, he perceived among the colonists signs of resistance so stern and resolute that he was glad to take the advice of Mr. Latrobe and sail for Sydney. But in Sydney also the arrival of the convicts was viewed with the most intense disgust. The inhabitants held a meeting on the Circular Quay, in which they protested very vigorously against the renewal of transportation to New South Wales. West Australia alone accepted its share of the convicts; and we have seen how the reputation of that colony suffered in consequence.

6. The Anti-Transportation League.—The vigorous protest of the other colonies had procured their immunity from this evil in its direct form; but many of the “ticket-of-leave men” found their way to Victoria and New South Wales, which were, therefore, all the more inclined to assist Tasmania in likewise throwing off the burden. A grand Anti-Transportation League was formed in 1851; and the inhabitants of all the colonies banded themselves together to induce the Home Government to emancipate Tasmania. Immediately after this, the discovery of gold greatly assisted the efforts of the league, because the British Government perceived that prisoners could never be confined in Tasmania, when, by escaping from the colony, and mixing with the crowds on the goldfields, they might not only escape notice but also make their fortunes; and there was now reason to suppose that banishment to Australia would be rather sought than shunned by the thieves and criminals of England.

7. End of Transportation.—In 1850 Tasmania, like the other colonies, received its Legislative Council; and when the people proceeded to elect their share of the members, no candidate had the slightest hope of success who was not an adherent of the Anti-Transportation League. After this new and unmistakable expression of opinion, the English authorities no longer hesitated, and the new Secretary of State, the Duke of Newcastle, directed that, from the year 1853, transportation to Tasmania should cease.

Up to this time the island had been called Van Diemen’s Land. But the name was now so intimately associated with ideas of crime and villainy, that it was gladly abandoned by the colonists, who adopted, from the name of its discoverer, the present title of the colony.

Sir Henry Young, formerly Governor of South Australia, was appointed to Tasmania in 1855, and held office till 1861. During this period responsible government was introduced. When the Legislative Council undertook the task of drawing up the new Constitution, it was arranged that the nominee element, which had now become extremely distasteful, should be entirely abolished, and that both of the legislative bodies should be elected by the people.

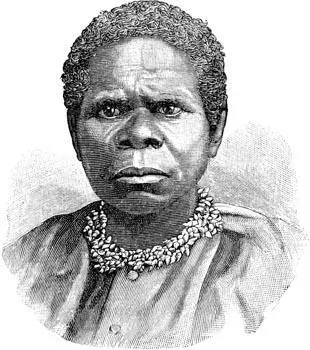

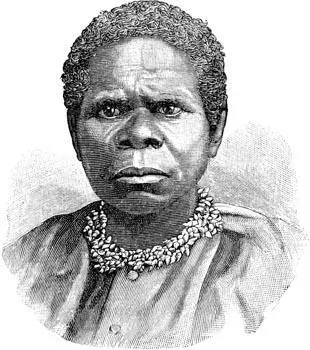

Queen Truganina, the Last of the Tasmanians.

After Sir Henry Young, the next three Governors were Colonel Browne, Mr. Du Cane, and Mr. Weld—all men of ability, and very popular among the Tasmanians. After the initiation of responsible government in 1856, various reforms were introduced. By a very liberal Land Act of 1863, inducements were offered to industrious men to become farmers in the colony. For the purpose of opening up the country by means of railways, great facilities were given to companies who undertook to construct lines through the country districts; and active search was made for gold and other metals. But, in spite of these reforms, the population was steadily decreasing, owing to the attractions of the gold-producing colonies. No great amount of land was occupied for farming purposes, and even the squatters on the island were contented with smaller runs than those in the other colonies. They reared stock on the English system, and their domains were sheep-farms rather than stations. Indeed, the whole of Tasmania wore rather the quiet aspect of rural England than the bustling appearance of an Australian colony. But the efforts to throw off the taint of convictism were crowned with marked success; and, from being a gaol for the worst of criminals, Tasmania has become one of the most moral and respectable of the colonies.

Читать дальше