Jaynes believes that everyone in the Homeric era and earlier lived in a world of delusion until, as he sees it, the right side of the brain gained supremacy over the left. In Jaynes’s view, then, each individual, although believing himself addressed by a god equally present to everyone else, was in fact trapped in a private delusion. The problem with this view is that, because hallucinations are, almost by definition, non-con-sensual, it would lead you to expect these people to live in a totally chaotic and barbaric state, characterized by complete mutual misunderstanding. Modern clinical psychiatrists define a schizophrenic as someone who cannot distinguish between externally and internally generated images and sounds. Clinical madness causes extreme, disabling distress together with impairment of domestic, social and occupational functioning. Instead the people of this era constructed the first post-Flood civilizations with separation between priestly, military, agricultural, trading and manufacturing orders. Organized labour forces engineered great public edifices, including canals, ditches and, of course, temples. There were complex economies and large, disciplined armies. In order for these peoples to have cooperated surely the hallucinations would have had to be group hallucinations? If the ancient world-view was a delusion, it had to have been a massive, almost infinitely complex and sophisticated delusion.

What I have tried to present so far is a history of the world as it was understood by ancient peoples who had a mind-before-matter world-view in which everyone collectively experienced gods, angels and spirits as interacting with them.

Thanks to Freud and Jung we are all familiar with the idea that our minds contain psychological complexes which are independent of our centres of consciousness and so to some degree may be thought of as autonomous. Jung described these major psychological complexes in terms of the seven major planetary deities of mythology, calling them the seven major archetypes of the collective unconscious.

Yet when Jung met Rudolf Steiner, who believed in disembodied spirits, including the planetary gods, Jung dismissed Steiner as a schizophrenic. We shall see in Chapter 27 how very late in life, shortly before he died, Jung went beyond the pale as far as the modern scientific consensus goes. He concluded that these psychological complexes were autonomous in the sense of being independent of the human brain altogether . In this way Jung took one step further than Jaynes. By no longer seeing the gods as hallucinations — whether individual or collective — but as higher intelligences, he embraced the ancient mind-before-matter philosophy.

The reader should beware of taking the same step. It is important you be on your guard against any impression that perhaps — to be fair — this version of history hangs together in some way, or that it feels true in some unspecific poetic or, worse, spiritual way. Important because a momentary lapse of concentration in this regard and you might, without at first noticing it and with a light heart and a spring in your step, begin to walk down the road that leads straight to the lunatic asylum.

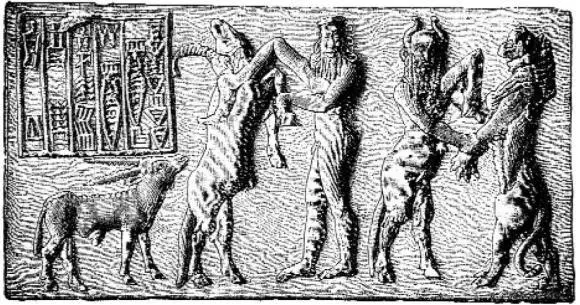

A representation on a cylinder seal of two heroes hunting, said to be Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

GILGAMESH, THE GREAT HERO OF SUMERIAN civilization, was king of Uruk in approximately 2100 BC. His story is full of madness, extreme emotion, anxiety and alienation. The great poet Rainer Maria Rilke called it ‘the epic of death-dread’.

The story as laid out here has largely been pieced together from clay tablets excavated in the nineteenth century, but it seems nearly complete.

At the start of his story the young king is called the ‘butting bull’. He is bursting with energy, opening mountain passes, digging wells, exploring, going into battle. He is stronger than any other man, beautiful, courageous, a great lover from whom no virgin is safe — but lonely. He longs for a friend, someone who is his equal.

So the gods created Enkidu. He was as strong as Gilgamesh but was wild, with matted hair all over his body. He lived among wild beasts, ate as they did and drank from streams. One day a hunter came face to face with this strange creature in the woods and reported back to Gilgamesh.

When he heard the hunter’s story, Gilgamesh knew in his heart that this was the friend he had been waiting for. He devised a brilliant plan. He instructed the most beautiful of the temple prostitutes to go naked into the woods, to find the wild man and tame him. When she made love to him he forgot, as Gilgamesh had known he would, about his home in the hills. Now when Enkidu came across wild animals they sensed the difference and no longer ran with him — they ran away from him.

When Gilgamesh and Enkidu met in the marketplace at Uruk there was a wrestling match of champions. The whole population crowded round to watch. Gilgamesh finally won, flinging Enkidu on to his back while still keeping his own foot on the ground.

So a famous friendship started a series of adventures. They hunted panthers and tracked down the monstrous Hawawa who guarded the way though the cedar forest. When they later slew the bull of heaven, Gilgamesh had the horns mounted on the walls of his bed chamber.

But then Enkidu fell dangerously sick. Gilgamesh sat by his bed six days and seven nights. Finally a worm fell out of Enkidu’s nose. At the end Gilgamesh drew a veil across his old friend’s face and roared like a lioness that has lost her cubs. Later he roamed the steppe, weeping, fear of his own death beginning to gnaw at his entrails.

Gilgamesh ended up at the tavern at the end of the world. He wanted to get out of his head. He asked the beautiful barmaid the way to Ziusudra, whom, we have seen, is another name for Noah or Dionysus. Ziusudra was a demi-god who had never really died.

Gilgamesh made a boat with punting poles topped with bitumen, such as are still used by marsh Arabs to this day, and went to meet the seer. Ziusudra said, ‘I will reveal to you a secret thing, a secret of the gods. There is at the bottom of the sea a plant that pricks like the rose. If you can bring it back up to the surface, you can become young again. It is the plant of eternal youth.’

Ziusudra was telling him how to dive beneath the seas that covered Atlantis, how to find the esoteric lore that had been lost at the time of the Flood. Gilgamesh tied stones to his feet like the local pearl-divers, descended, plucked the plant, cut himself free of the stones and rose to the surface in triumph.

But while he was resting on the shore from his exertions, a snake smelled the plant and stole it.

Gilgamesh was as good as dead.

WHEN WE READ THE STORY OF GILGAMESH we may be intrigued to see how he fails the test that humanity’s great leader has set him. There is a note of anxiety here that can then be heard spreading ever more widely in the Babylonian and Mesopotamian civilizations that grew up to dominate this region.

With the death of Gilgamesh we are in the time of the greatest ziggurats. The story of the Tower of Babel, the attempt to build a tower up to heaven and the resulting loss of a single language uniting all humanity, represents the fact that as nations and tribes began to become attached to their own tutelary spirits and guiding angels, they lost sight of the higher gods and the great cosmic mind beyond that gives all the different parts of the universe one destiny. The ziggurats represent a misguided attempt to scale the heavens by material means.

The Tower of Babel was built by Nimrod the Hunter. Genesis calls Nimrod ‘the first potentate on earth’. The archaeologist David Rohl has convincingly identified Nimrod with the historical Enmer-kar (‘Enmer the Hunter’), the first king of Uruk who wrote to the neighbouring king of Aratta, demanding tribute money in what is believed to be the earliest surviving letter.

Читать дальше