From the point of view of the secret history this interpretation is anachronistic. It was the universal belief at this time that all human spirits travelled up through the planetary spheres to the stars after death. In fact, as we have seen, the living still had such vivid experience of the spirit worlds that it would have been as hard for them to decide to disbelieve in the reality of the after-death journey as it would be hard for us to decide to disbelieve in the reality of the book or table in front of us.

We should look elsewhere for an explanation of the function of the Great Pyramid. The whole tenor of ancient Egyptian civilization is that it was trying to get to grips with matter. We see this in its innovatory drive to cut and carve stone.

We also see the new relation to matter in the practice of mummifying. We are never more ready to ascribe stupid beliefs to the ancients than when we link Egyptian mummification and elaborate grave goods to a supposed belief that the spirit might actually want to use these grave goods in the afterlife. The point of these burial practices, according to esoteric thought, is rather that they exerted a sort of magnetic attraction on the ascending spirit that would help it attain speedy reincarnation. It was believed that if the discarded body were preserved, it would remain a focus for the spirit that had left it, exerting an attraction that pulled it down to earth again.

The esoteric explanation of the Great Pyramid is similar. We saw in Chapter 7 that the great gods, finding it increasingly difficult to incarnate, had retreated as far as the moon, visiting the earth increasingly rarely.

The Great Pyramid is a gigantic incarnation machine.

EGYPTIAN CIVILIZATION REPRESENTS A great new impulse in human evolution, very different from the oriental civilization which had taught that matter is maya, or illusion. The Egyptians initiated the great spiritual mission of the West, sometimes called in alchemy, Sufism Freemasonry, and elsewhere in the secret societies, the Work . The mission was to work on matter, to cut it, carve it, to imbue it with intention until every particle of matter in the universe has been worked on and spiritualized. The Great Pyramid was the first manifestation of this urge.

THIS HISTORY IS ABOUT CONSCIOUSNESS in different ways.

First, this history has been told in various groups who have made it their aim to work themselves into altered states of consciousness.

Second, this history supposes that consciousness has changed over time in a far more radical way than conventional historians allow.

Third, it suggests that the mission of these groups is to lead the evolution of consciousness. In a mind-born universe the end and aim of creation is always mind.

I want to focus now on the second of these ways, to show that some academics have recently written in support of the esoteric view that consciousness used to be very different from what it is today.

Contemporary with the rise of Egyptian civilization in about 3250 BC Sumerian civilization arose in the land between the Tigris and the Euphrates. In the early cities of Sumeria statues to ancestors and lesser gods stood in family homes. A skull was sometimes kept as a ‘house’ that a minor spirit could inhabit. Meanwhile, the much greater spirit who protected the interests of the city was held to live in the ‘god house’, a building at the centre of the temple complex.

As these cities grew, so too did the god houses, until they became ziggurats, great rectangular, stepped pyramids, built out of mud bricks. In the centre of each ziggurat was a large chamber in which the statue of the god resided, inlaid with precious metals and jewels, and wrapped in dazzling clothes.

According to the cuneiform texts, the Sumerian gods liked eating, drinking, music and dancing. Food would be put on tables, then the god left alone to enjoy it. After a time the priests would come in and eat what was left. The gods also needed beds to sleep in and for enjoying sex with other gods. They had to be washed for this and dressed and anointed with perfumes.

As with the grave goods in Egypt, the aim of these practices was to try to tempt gods to inhabit the material plane, by reminding them of the sensual pleasures denied them in the spirit worlds.

The bee is one of the most important symbols in the secret tradition. Bees understand how to build their hives with a sort of pre-conscious genius. Bee-hives incorporate exceptionally difficult and precise data in their construction. For example, all hives have built into them the angle of the earth’s rotation. Sumerian cylinder seals of this time show figures with human bodies but bees’ nests for heads. This is because in this period an individual’s consciousness was experienced as made up of a collaboration of many different centres of consciousness, in the way we described in Chapter 2. These centres could be shared or even moved from one mind to another like a swarm of bees from one hive to another.

Bee-hive headed Sumerian goddesses.

A brilliant analysis of Sumerian and other ancient texts by Princeton Professor of History Julian Jaynes was published in 1976. The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bi - Cameral Mind argued that during this period humans had no concept of an interior life as we understand it today. They had no vocabulary for it, and their narratives show that features of mental life, such as willing, thinking and feeling which we experience as somehow generated ‘inside’ us, they experienced as the activity of spirits or gods in and around their bodies. These impulses happened to them at the bidding of disembodied beings that lived independently of them, rather than arising inside themselves at their own bidding.

It is interesting that the Jaynes analysis chimes with the esoteric account of ancient history given by Rudolf Steiner. Born in Austria in 1861, Steiner represents a genuine stream of Rosicrucian thinking, and he is the esoteric teacher of modern times who has given the most detailed account of the evolution of consciousness. Jaynes’s researches are, as far I know, independent of this tradition.

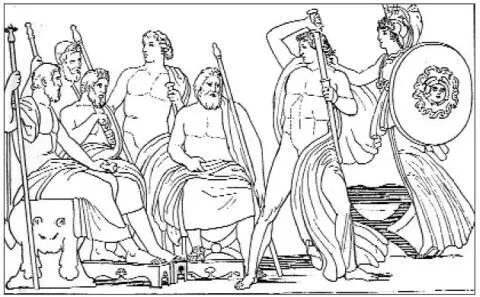

It is perhaps easier to appreciate Jaynes’s analysis in relation to the more familiar Greek mythology. In the Iliad , for example, we never see anyone in any sense sit down and work out what to do, in the way we see ourselves doing. Jaynes shows that for the people of the Iliad there is no such thing as introspection. When Agamemnon robs Achilles of his mistress, Achilles does not decide to restrain himself. Rather, a god accosts him by the hair, warning him not to strike Agamemnon. Another god rises out of the sea to console him, and it is a god who whispers to Helen of homesick longing. Modern scholars tend to interpret these passages as ‘poetic’ descriptions of interior emotions, in which the gods were symbols of the sort a modern poet might create. Jaynes’s clear-sighted reading shows that this interpretation reads present-day consciousness back into texts written by people whose form of consciousness was very different. Neither is Jaynes alone in his view. The Cambridge philosopher John Wisdom has written: ‘The Greeks did not speak of the dangers of repressing instincts but they did think of thwarting Dionysius or of forgetting Poseidon for Athena.’

The most famous depiction of other worldly suggestion is the statue in the Cairo Museum which shows Horus whispering in the ear of the pharaoh Kefren.

Here Athena restrains Achilies from striking Agamemnon, in a drawing by Flaxman, who was an initiate of the secret societies, and a demon sits on the shoulder of a saint.

We shall see in the concluding chapters of this history how the ancient form of consciousness continued to thrive very much later than even Jaynes posits. For the moment, though, I want to touch on a significant difference between Jaynes’s analysis and the way the ancients themselves understood things. Jaynes describes the gods who control the actions of the humans as being ‘aural hallucinations’. The kings of Sumeria and heroes of Greece are depicted by him as being, in effect, beset by delusions. In the ancient view, by contrast, these were not, of course, mere delusions but independent, living beings.

Читать дальше