Reinhardt worried about the implications of releasing the diaries to the world. She saw the diaries as political dynamite with the potential to wreck Sino-Japanese relations. But at my urging, and also at the urging of Shao Tzuping, a past president of the Alliance in the Memory of Victims of the Nanking Massacre who worked for the United Nations, she decided to make the diaries public. She spent fifteen hours photocopying them. Shao, who was fearful that right-wing Japanese might break into her house and destroy the diaries or offer the family large sums of money to buy up the originals, hastily flew Ursula Reinhardt and her husband to New York City, where copies of the diaries were donated to the Yale Divinity School library at a press conference that was first announced by a prominent story in the New York Times and then covered by Peter Jennings of ABC-TV, CNN, and other world media organizations on December 12, 1996—the fifty-ninth anniversary of the fall of Nanking.

Historians were unanimous in their proclamation of the diaries’ value. Many saw the diaries as more conclusive proof that the Rape of Nanking really did occur, and as an account told from the perspective of a Nazi, they found it fascinating. Rabe’s account added authenticity to the American reports of the massacre, not only because a Nazi would have lacked the motive to fabricate stories of the atrocities, but also because Rabe’s records included translations of the American diaries from English to German that matched the originals word for word. In the PRC, scholars announced to the Renming Ribao that the documents verified and corroborated much of the existing Chinese source material on the massacre. In the United States, William Kirby, a professor of Chinese history at Harvard University, told the New York Times: “It’s an incredibly gripping and depressing narrative, done very carefully with an enormous amount of detail and drama. It will reopen this case in a very important way in that people can go through the day-by-day account and add 100 to 200 stories to what is popularly known.”

Even Japanese historians pronounced the Rabe finding important. Kasahara Tokushi, a professor of modern Chinese history at Utsunomiya University, testified to the Asahi Shimbun: “What makes this report significant is the fact that, not only was it compiled by a German, an ally of Japan, Rabe submitted the report to Hitler to make him aware of the atrocities occurring in Nanking. The fact that Rabe, who was a vice-president of the Nazi Party, entreated Hitler, the top leader of a Japanese ally, to intervene testifies to the tremendous scale of the massacre.” Hata Ikuhiko, a professor of modern Japanese history at the University of Chiba, added: “The meaning of this report is significant in the sense that a German, whose country was allied with Japan, depicts the atrocity of Nanking objectively. In that sense, it has more value as a historical document than the testimony of the American pastor. At the time, Germany was not sure which side to take, either Japan’s or China’s. However, Ribbentrop’s inauguration as foreign minister fostered Germany’s alliance with Japan. It is amazing how brave he was by trying to let Hitler know of the atrocity in Nanking at such a critical time.”

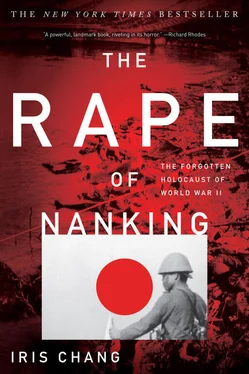

10. THE FORGOTTEN HOLOCAUST: A SECOND RAPE

IS THERE a child today in any part of the United States, and perhaps in many other parts of the world, who has not seen the gruesome pictures of the gas chambers at Auschwitz or read at least part of the haunting tale of the young Anne Frank? Indeed, at least in the United States, most schoolchildren are also taught about the devastating effects of the atomic bombs the United States dropped over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But ask most Americans—children and adults alike, including highly educated adults—about the Rape of Nanking, and you will learn that most have never been told what happened in Nanking sixty years ago. A prominent government historian admitted to me that the subject had never once come up in all her years of graduate school. A Princeton-educated lawyer told me sheepishly that she was not even aware that China and Japan had been at war; her knowledge of the Pacific conflict of World War II had been limited to Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima. The ignorance extends even to Asian Americans in this country. One of them revealed her woeful grasp of geography and history when she asked me, “Nanking? What was that, a dynasty?”

An event that sixty years ago made front-page news in American newspapers appears to have vanished, almost without a trace. Hollywood has not produced a mainstream movie about the massacre—even though the story contains dramatic elements similar to those of Schindler’s List. And until recently most American novelists and historians have also chosen not to write about it.

After hearing such remarks, I became terrified that the history of three hundred thousand murdered Chinese might disappear just as they themselves had disappeared under Japanese occupation and that the world might actually one day believe the Japanese politicians who have insisted that the Rape of Nanking was a hoax and a fabrication—that the massacre never happened at all. By writing this book, I forced myself to delve into not only history but historiography—to examine the forces of history and the process by which history is made. What keeps certain events in history and assigns the rest to oblivion? Exactly how does an event like the Rape of Nanking vanish from Japan’s (and even the world’s) collective memory?

One reason information about the Rape of Nanking has not been widely disseminated clearly lies in the postwar differences in how Germany and Japan handled their wartime crimes. Perhaps more than any other nation in history, the Germans have incorporated into their postwar political identity the concession that the wartime government itself, not just individual Nazis, was guilty of war crimes. The Japanese government, however, has never forced itself or Japanese society to do the same. As a result, although some bravely fight to force Japanese society to face the painful truth, many in Japan continue to treat the war crimes as the isolated acts of individual soldiers or even as events that simply did not occur.

In Japan competing stories of what happened during World War II continue to appear. According to a currently popular revisionist view, the country bears no responsibility for the wholesale murder of civilians anywhere during the war. The Japanese fought the war to ensure its own survival and to free Asia from the grip of Western imperialism. Indeed, in return for its noble efforts, Japan itself ended up as the ultimate victim at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

This soothing perception of history still finds its way into Japanese history textbooks, which have either ignored the massacre at Nanking altogether or put a decidedly Japanese spin on the actions of the military. At the far end of the political spectrum, Japanese ultranationalists have threatened everything from lawsuits to death, even assassination, to silence opponents who suggest that these textbooks are not telling the next generation the real story.

But it is not just fanatical fringe groups that are trying to rewrite history. In 1990 Ishihara Shintaro, a leading member of Japan’s conservative Liberal Democratic Party and the author of best-selling books such as The Japan That Can Say No, told a Playboy interviewer: “People say that the Japanese made a holocaust there [in Nanking], but that is not true. It is a story made up by the Chinese. It has tarnished the image of Japan, but it is a lie.”

Naturally, this statement enraged scholars and journalists around the world. One proclaimed that “Japan’s denial of the rape of Nanjing would be politically the same as German denial of the Holocaust.” But the denunciations failed to silence Ishihara, who responded with a furious stream of counterattacks. In his rebuttals, Ishihara, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, asserted that the world never learned about the Nanking massacre until the International Military Tribunal of the Far East put people on trial for their role in it; that neither Japanese war correspondents nor Western reporters wrote about the massacre as it was occurring; that the New York Times correspondent Frank Tillman Durdin failed to witness any massacre; and that the Episcopalian minister John Magee saw only one person killed.

Читать дальше