Though the sale of opium and heroin thrived under Japanese rule, the population of Nanking remained relatively free of disease. After occupation, Japanese authorities in the city enacted rigorous policies to burn corpses that had perished from illness. They also began an aggressive inoculation program against cholera and typhoid, subjecting the people to shots several times a year. Chinese medical officers waited in the streets and in the train station to administer inoculations to pedestrians or visitors as they came into the city. This created great resentment among the civilians, many of whom feared the needles would kill them. Children of Western missionaries also remember that at the train station Chinese visitors to Nanking were ordered to step into pans of disinfectant—a requirement that many found deeply humiliating. (The Westerners themselves were often sprayed with Lysol upon entering the city.)

Within a few years Nanking pulled itself up from its ruins. In the spring of 1938, men started to venture back to the city—some to examine the damage, others to find work because they had run out of money, still others to see whether conditions were safe enough for their families to return. As reconstruction began, the demand for labor grew. Soon, more men were lured back, and before long their wives and children joined the influx of migration toward Nanking. Within a year and a half, the population had doubled, surging from an estimated 250,000–300,000 people in March 1938 to more than 576,000 people in December 1939. Though the population failed to reach the 1-million level that the city had enjoyed back in 1936, by 1942 the population peaked at about 700,000 people and stabilized for the duration of the war.

Life under the Japanese was far from pleasant, but a sense of resignation settled over the city as many came to believe that the conquerors were there to stay. Occasionally there was underground resistance—once in a while someone would run into a theater packed with Japanese officials and throw a bomb—but in general such rebellion was sporadic and rare. Most of the hostility against the Japanese was expressed nonviolently, such as in anti-Japanese posters, fliers, and graffiti.

The end of Nanking’s ordeal came at last in the summer of 1945. On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an untested uranium bomb on Hiroshima, Japan’s eighth-largest city, killing 100,000 of its 245,000 people on the first day. When a Japanese surrender was not forthcoming, the Americans dropped, on August 9, a second, plutonium-type bomb on the Japanese city of Nagasaki. Less than a week later, on August 14, the Japanese made the final decision to surrender.

The Japanese remained in the former capital of China until the day of the surrender, then quickly left the city. Eyewitnesses reported that Japanese soldiers could be seen drinking heavily or weeping in the streets; some heard rumors of unarmed Japanese men being forced to kneel by the side of the road to be beaten by local residents. Retaliation against the Japanese garrison appears to have been limited, however, because many residents hid at home during this chaotic time, too fearful to even celebrate in case the news of a Japanese defeat turned out not to be true. The evacuation was swift, and there was no mass persecution or imprisonment of Japanese soldiers. One Nanking citizen recalls that she stayed in her house for weeks after the Japanese surrendered, and when she reemerged, they were gone.

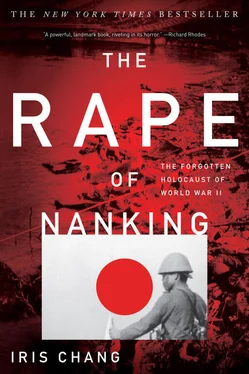

EVEN BEFORE World War II drew to a close, the Allies had organized war tribunals to bring Japanese military criminals to justice. Fully expecting a Japanese defeat, the American and Chinese Nationalist governments made preliminary arrangements for the trials. In March 1944, the United Nations created the Investigation of War Crimes Committee; a subcommittee for Far East and Pacific war crimes was established in Chungking, China’s wartime capital, after the fall of Nanking. After the Japanese surrender, the planning of the tribunals began in earnest. The Supreme Command of the Allied Powers in Japan worked closely with the Chinese Nationalist government to gather information about Japanese atrocities in China. For the crimes committed during the Rape of Nanking, members of the Japanese establishment stood trial not only in Nanking but in Tokyo itself.

THE NANKING WAR CRIMES TRIAL

The Rape of Nanking had been a deep, festering wound in the city’s psyche, a wound that hid years of repressed fear and hatred. When the trials for class B and C war criminals started in the city in August 1946, the wound ruptured, spilling forth all the poison that had accumulated during the war.

Only a handful of Japanese war criminals were tried in Nanking, but they gave the local Chinese citizens a chance to air their grievances and participate in mass catharsis. During the trials, which lasted until February 1947, more than 1,000 people testified about some 460 cases of murder, rape, arson, and looting. The Chinese government had posted notices in the streets of Nanking, urging witnesses to come forward with evidence, while twelve district offices collected statements from people all over the city. One after another, they appeared in the courtroom, listened to the Chinese judge warn them about the five-year sentence for perjury, and then swore an oath of truth by marking printed statements with signatures, seals, fingerprints, or crosses. The witnesses included not only Chinese survivors but some of the Safety Zone leaders, such as Miner Searles Bates and Lewis Smythe.

During the trials evidence that had been painstakingly hidden for years emerged. One of the most famous exhibits was a tiny album of sixteen photographs of atrocities taken by the Japanese themselves. When the negatives were brought to a film development shop during the massacre, the employees secretly duplicated a set of images, which were placed in an album, hidden in the wall of a bathroom, and later secreted under a statue of Buddha. The album passed from hand to hand; men risked their lives to hide it even when the Japanese issued threats and conducted searches for photographic evidence of their crimes. One man even fled from Nanking and wandered from city to city for years like a fugitive because of the sixteen photographs. (The long and complex journey that these pictures made from photo shop to war crimes trial to their final resting place in archives has inspired numerous articles and even a full-length documentary in China.)

But not all of the evidence had taken such a sensational, circuitous path to the courtroom. Some came straight from old newspaper clippings. A Japan Advertiser article was brought forth at the trial of two lieutenants, Noda Takeshi and Mukai Toshiaki, who had participated in the famous killing contest described in chapter 2. During the trial both soldiers, of course, denied killing more than 150 people each, one of them blaming the article on the imagination of the foreign correspondents and the other insisting that he lied about the contest to better attract a wife when he returned to Japan. When the verdict was read in the courtroom on December 18, 1947, the Chinese audience whooped, cheered, and wept for joy. Both lieutenants were executed by firing squad.

The focal point of the Nanking war crimes trials was Tani Hisao. In 1937 he had served as lieutenant general of the 6th Division of the Japanese army in Nanking, a division that perpetrated many of the atrocities in the city, especially around Chunghua Gate. In August 1946, Tani was brought back to China for his trial and hauled in a prison van to a detention camp in Nanking. To prepare for his prosecution, forensic experts in white overalls dug open five burial grounds near the Chunghua Gate and exposed thousands of skeletons and skulls, many cracked from gunshot wounds and still stained with dark blood.

Читать дальше