The sheer number of refugees eventually overwhelmed Vautrin. Hundreds of women crammed themselves into verandas and covered ways head to feet, and many more women slept outside on the grass at night. The attic of Ginling’s Science Hall housed more than one thousand women, and a friend of Vautrin’s noted that women “slept shoulder to shoulder on the cement floor for weeks on end during the cold winter months! Each cement step in the building was the home of one person—and those steps are not more than four feet long! Some were happy to have a resting place on the chemistry lab tables, the water pipes and other paraphernalia not interfering at all.”

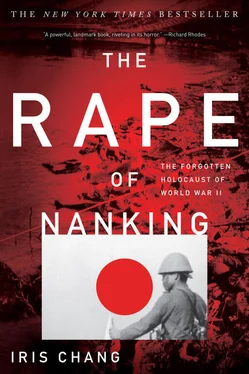

The Rape of Nanking wore down Vautrin physically, but the mental torture she endured daily was far worse than her physical deterioration. “Oh, God, control the cruel beastliness of the soldiers in Nanking tonight… ” she wrote in her diary. “How ashamed the women of Japan would be if they knew these tales of horror.”

Under such pressure, it is remarkable that Vautrin still found the spirit to comfort others and give them a renewed sense of patriotism. When an old lady went to the Red Cross kitchen at Ginling College to fetch a bowl of rice porridge, she learned that there was no porridge left. Vautrin immediately gave her the porridge she had been eating and said to her: “Don’t you people worry. Japan will fail. China will not perish.” Another time, when she saw a boy wearing an armband marked with the Japanese symbol of the rising sun to ensure his safety, Vautrin scolded him and said: “You do not need to wear this rising sun emblem. You are a Chinese and your country has not perished. You should remember the date you wear this thing, and you should never forget.” Again and again, Vautrin urged the Chinese refugees on campus never to lose faith in their future. “China has not perished,” she told them. “China will never perish. And Japan will definitely fail in the end.”

Others could see how hard she was working. “She didn’t sleep from morning till night,” one Chinese survivor recalled. “She kept watching and if Japanese soldiers came… she would try her best to push them out and went out to their officials to pray them not to do so much evil things to the Chinese women and children.” “It was said that once she was slapped several times by beastly Japanese soldiers,” another wrote in his eyewitness account of the Nanking massacre. “Everyone was worried about her. Everyone tried to comfort her. She still fought for the cause of protecting Chinese women with courage and determination from beginning to end.”

The work of running the zone was not only physically taxing but psychologically debilitating. Christian Kröger, a Nazi member of the International Committee, claimed that he saw so many corpses in the streets that he soon suffered nightmares about them. But in the end, under unbelievable circumstances, the zone saved lives. Here are some startling facts:

—Looting and arson made food so scarce that some Chinese refugees ate the Michaelmas daisies and goldenrod growing on the Ginling College campus or subsisted on mushrooms found in the city. Even the zone leaders went hungry from lack of meals. They not only provided free rice to the refugees through soup kitchens but delivered some of it directly to refugee compounds, because many Chinese in the zone were too scared to leave their buildings.

—Bookish and genteel, most of the zone leaders had little experience in handling a horde of rapists, murderers, and street brawlers. Yet they acted as bodyguards for even the Chinese police in the city and somehow, like warriors, found the physical energy and raw courage to throw themselves in the line of fire—wrestling Chinese men away from execution sites, knocking Japanese soldiers off of women, even jumping in front of cannons and machine guns to prevent the Japanese from firing.

—In the process, many zone leaders came close to being shot, and some received blows or cuts from Japanese soldiers wielding bayonets and swords. For example: Charles Riggs, a University of Nanking professor of agricultural engineering, was struck by an officer when he tried to prevent him from taking away a group of Chinese civilians mistaken as soldiers. The infuriated Japanese officer “threatened Riggs with his sword three times and finally hit him hard over the heart twice with his fist.” A Japanese soldier also threatened Professor Miner Searle Bates with a pistol. Another soldier pulled a gun on Robert Wilson when he tried to kick out of the hospital a soldier who had crawled into bed with three girls. Still another soldier fired a rifle at James McCallum and C. S. Trimmer but missed. When Miner Searle Bates visited the headquarters of the Japanese military police to learn the fate of a University Middle School student who had been tied up and carried off by soldiers, the Japanese shoved Bates down a flight of stairs. Even the swastikas the Nazis carried about like amulets occasionally failed to protect them from assault. On December 22, John Rabe wrote that Christian Kröger and another German named Hatz were attacked when they tried to save a Chinese man who had been wounded in the throat by a drunken Japanese soldier. Hatz defended himself with a chair, but Kröger apparently ended up being tied and beaten.

—The zone eventually accommodated some 200,000–300,000 refugees—almost half the Chinese population left in the city.

The last is a chilling statistic when placed in the context of later studies of the Nanking massacre. Half the original inhabitants of Nanking left before the massacre. About half of those who stayed (350,000 people out of the 600,000–700,000 Chinese refugees, native residents, and soldiers in the city when it fell) were killed.

If half of the population of Nanking fled into the Safety Zone during the worst of the massacre, then the other half—almost everyone who did not make it to the zone—probably died at the hands of the Japanese.

THE WORLD was not kept in the dark about the Rape of Nanking; news of the massacre continuously reached the global public while events unfolded. For months before the fall of Nanking, numerous foreign correspondents lived in the capital to cover its aerial bombardment by Japanese aviators. As the Japanese army neared the doomed capital in early December, reporters provided vivid and almost daily coverage of battles, fires, last-minute evacuations, and the creation of the International Safety Zone. Amazingly, when the massacre began, Japanese newspapers ran photographs of Chinese men being rounded up for execution, heaps of bodies waiting for disposal by the riverside, the killing contests among the Japanese soldiers, and even the shocked commentary of the reporters themselves.

Apparently, before international opinion kicked in, the first few days of the massacre were a source of tremendous pride to the Japanese government. Celebrations broke out across Japan when the people heard the news of Nanking’s defeat. Special meals of Nanking noodles were prepared in Tokyo, and children across Japan carried globe-shaped, candle-lit paper lanterns in evening parades to symbolize the ascendancy of the rising sun. It was only later, after news of the sinking of the Panay and the butchering of Nanking citizens had met with international condemnation, that the Japanese government quickly tried to hide what its army had done and replaced the news with propaganda. Thanks to the efforts of a few American journalists, the Japanese as a nation soon faced a scandal of gargantuan proportions.

The journalists who had the greatest influence on Western foreign opinion at the time were three American foreign correspondents: Frank Tillman Durdin of the New York Times, Archibald Steele of the Chicago Daily News, and C. Yates McDaniel of the Associated Press. An adventurous streak ran through all three men. Durdin, a twenty-nine-year-old reporter from Houston, had spent time mopping decks and cleaning winches on a freighter to secure free passage from the United States to China. Once in Shanghai, he worked for a daily English-language newspaper and soon moved on to the Times to cover the Sino-Japanese War. Steele was an older correspondent who had reported on the Japanese occupation of Manchuria and the expanding Asian war. McDaniel was perhaps the most daring of the three: before the massacre he had driven through battle lines in the countryside, barely escaping death from exploding shells during his quest “to find the war.”

Читать дальше