Demjanjuk repeatedly crossed himself during Blatman’s plea.

Defense counsel John Gill reminded the court of the Frank Walus case in Chicago, where eleven survivor eyewitnesses had been wrong. He further argued that the death penalty was morally unacceptable. “Tendencies in enlightened countries has [sic] been away from it,” Gill pleaded. “Don’t commit a second horrendous crime.”

After the prosecution and defense completed their arguments for and against the death penalty, Judge Dov Levin gave the floor to John Demjanjuk.

“The convicted man has the last word,” he said.

Demjanjuk pleaded: “It has been very painful for me to listen to reports of the tragedy that befell your people during the Nazi period. Six million died a terrible death, and I hope they reached the kingdom of heaven. I believe there was an Ivan the Terrible, but I was not that man. Last week you convicted me. And you made a big mistake, and God will be my witness.”

The court recessed for three hours. When the judges returned to the courtroom, Demjanjuk shouted in Hebrew, “I am innocent!”

Judge Zvi Tal then read the sentence in a flat voice devoid of all emotion: “Most things can be forgiven, but in this case there is no forgiving, not in law and not in feeling. Demjanjuk’s crimes stand above time. It is as if Treblinka still existed, Iwan were still swinging his sword or his iron pipe, cutting into live flesh, causing streams of blood…. There is no name to describe these crimes and there is no adequate punishment.

“We decree the death penalty.”

The courtroom erupted in joy. Spectators applauded and danced. They chanted “Death, death, death!” They sang folk songs. “Death to Iwan!” They wept and hugged. “Death to all Ukrainians!” They hurled threats at Yoram Sheftel. A group of school kids sang Am Israel Hai —The Jewish People Live! “Death! Death! Death!”

One lone survivor’s voice rose above the din: “May his name and memory be erased and forgotten!”

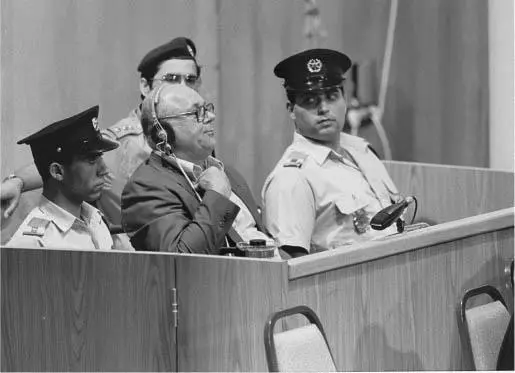

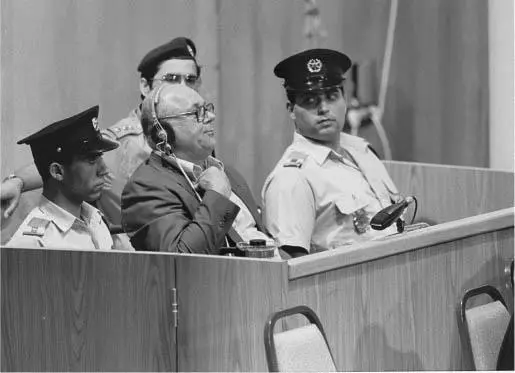

Demjanjuk crosses his heart upon hearing the pronouncement of his death sentence.

• • •

Ukrainian communities across the United States and Canada were shocked and angry.

“It’s a travesty of justice,” the Reverend John Bruchok, pastor of St. Mary’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Lorain, Ohio, said. “I saw his face. I saw the face of a gentle man.”

In Demjanjuk’s hometown of Parma, Ukrainians spoke out with bitterness:

“He was just a man, not a monster…”

“This is all a terrible mistake…”

“It stinks. They just needed a scapegoat…”

“It’s been so many years. And he doesn’t bother anybody. Why stir things up?”

“It’s like everyone’s saying the Ukrainians are the evil ones…”

As if to prove the point, vandals spray-painted St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Church, where the Demjanjuk family worshipped, with purple circles like targets.

For its part, the Jewish community hunkered down until the storm blew over. Cleveland rabbis reported threats to their synagogues. Akron Jews suffered such a barrage of threats that they asked for special police protection.

Editorials around the world called for a commutation to a life sentence both because there was a reasonable doubt about the validity of the evidence against Demjanjuk, and because to hang a man was barbaric.

The London Times spoke for many countries when it editorialized: “If Israeli authorities could see their way to commuting the death sentence, this would further mark the emergence of Israel as the civilized state it aspires to be.”

• • •

It was now up to the Supreme Court of Israel, which was required under Israeli law to review all death sentences. As final arbiter, it had the authority to commute Demjanjuk’s sentence to life in prison. Or it could uphold the defense appeal arguing judicial bias and vacate the verdict of Judge Levin’s court. All John Demjanjuk could do in his cell on death row was pray… and wait.

It would be a five-year wait.

While John Demjanjuk was on trial for his life in Israel, four noteworthy events were occurring elsewhere. If three of the events brought some measure of justice—or the promise of it—the fourth raised questions about the very existence of justice.

First, Klaus Barbie, the Butcher of Lyon, was sentenced to life in prison. Unlike Israel, France did not have the death penalty. Barbie died of leukemia four years later at the age of seventy-seven while Demjanjuk was sitting on death row.

Second, based on eyewitness testimony, the Soviets executed Feodor Fedorenko by firing squad for serving the Nazis as a guard at Treblinka and for beating and driving Jews into the gas chambers. The Soviets had waited until John Demjanjuk was safely locked in an Israeli prison, facing a hangman’s noose, before they executed Fedorenko. His death supported Demjanjuk’s argument that deporting him to the Soviet Union would have been a death sentence.

Third, the Soviet Union and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Council issued a joint statement that had implications for Demjanjuk’s future appeal before the Israeli Supreme Court. The Soviets agreed to open their archives on Nazi genocide to American historians and archivists. The agreement included an invitation to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, which had not yet opened, to microfilm or microfiche Soviet Holocaust-related documents, millions of which were haphazardly filed in a string of archives across the Soviet Union. The documents included records on Nazi executions of Jews, young communists, and Gypsies, as well as captured German documents like the three Trawniki ID cards that the Soviets had provided to Israeli prosecutors during the Demjanjuk trial.

The U.S.-Soviet agreement offered new hope to the Demjanjuk defense. Perhaps Moscow would grant Demjanjuk investigators permission to search for archival evidence proving that the testimony of Treblinka survivors had pushed the wrong man to the foot of the gallows.

Fourth, OSI released a lengthy report on Robert Jan Verbelen, a convicted Belgian Nazi collaborator who had worked for and was protected by the United States after the war. Reinforced by newly declassified government documents, the publication offered a glimpse into the inner sanctum of U.S. espionage in the “Dodge City” days just after World War II. During that time, America, England, and France were scrambling to gather information about the new threat to their national security—their former ally Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union. As illustrated by the following three accounts, the story the Verbelen report told was not a pretty one.

While the Justice Department was stalking John Demjanjuk as Nazi collaborator Ivan the Terrible of Treblinka, the CIA and the Justice Department were trying to protect the identity of a major convicted Nazi war criminal. His name was Robert Jan Verbelen. To the embarrassment of the intelligence establishment, however, Nazi hunters uncovered evidence that Verbelen had worked for the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) in Austria immediately after the war.

The Department of Justice handled the Verbelen leak the way it had dealt with the Klaus Barbie scandal. It commissioned OSI to unravel the story, and for the same reasons. The Justice Department didn’t want to be accused of a cover-up that could cripple or destroy the credibility of an already beleaguered OSI. And Justice wanted to manage the spin on the story to control the damage.

Читать дальше