The next step in the Demjanjuk family drama was obvious. Fire O’Connor. The problem was—the Demjanjuk family couldn’t sack him. The family wasn’t on trial, John Demjanjuk was. Court rules stipulated that the accused had to decide whom he wanted to represent him. And the problem was, John Demjanjuk didn’t seem to understand how badly his case was faring. Could his wife and children convince him to cut his emotional ties to O’Connor?

• • •

Demjanjuk’s behavior before and during the trial had been very erratic. One moment he was extending a hand to Treblinka survivor Eliyahu Rosenberg and saying, “Shalom!” The next moment he was calling the man a liar. One moment he was sitting passively in his dock listening to the trial over headphones, serene and seemingly uninterested, as if someone he didn’t know was on trial for his life. The next moment he seemed irritated. One moment he would ignore the taunting spectators. The next, he would clasp his hands in the air like a boxer who had just scored a KO and blow kisses to the gallery.

At one point, Demjanjuk shocked the entire courtroom—spectators, bench, prosecutors, and his own defense. He raised his hand at the end of the cross-examination of Professor Wolfgang Schefler. Judge Levin recognized him. Demjanjuk told Levin that he had some questions he wanted to ask the professor.

“These questions are very important to me,” Demjanjuk said. “I am a long time in jail now and I don’t know what the future may hold for me.”

O’Connor apologized to the court for the interruption. The prosecution objected. Levin granted the request. “This is a most important trial,” Levin said, ordering a microphone for Demjanjuk. “It is very important to the accused to ask one or two questions. The same questions—it appears to the accused—that the defense doesn’t manage to formulate properly.”

Historian Wolfgang Schefler, who had testified at the Cleveland denaturalization trial, was a prosecution expert witness on Trawniki. He had just finished answering cross-examination questions about the two kinds of uniforms—black and khaki—that he claimed the Trawniki men wore. And he had testified that the man in the picture on the Trawniki card appeared to be wearing the black uniform of a Trawniki man.

“Professor Schefler!” Demjanjuk began. His “cross-examination” would last forty-five minutes. “You said that black uniforms were introduced into Trawniki later, and at first there were some sort of yellowish uniform. I have heard that is not true, and I would like you to clarify this.”

Schefler told Demjanjuk that he didn’t say yellowish uniforms but khaki. When Demjanjuk kept pressing, Schefler lost his composure. “Maybe you tell us what happened,” he said.

Even Judge Levin seemed stunned by Schefler’s response. “This last offer is not acceptable,” Levin said. And O’Connor muttered loud enough for the bench to hear, “Impartial, huh?”

Demjanjuk next questioned Schefler about the alleged photograph of himself on the Trawniki card. “I saw it first eight years ago, and I’ve seen a great many, many things that apparently would show that this is a forgery.”

Demjanjuk then said something that stung the defense table. “For example,” he said, “I was also wearing a pullover.”

The defense almost cheered when Demjanjuk finally sat down. He had practically admitted being a Trawniki man… unless, of course, Demjanjuk had been mistranslated.

Demjanjuk exhibited the same mood swings in his Ayalon prison cell. At one point, he tried to push visiting police investigator Alex Ish-Shalom out the door. On other occasions, he chatted with him as if he were a friend instead of a cop on a fishing expedition. Demjanjuk remained so distant from the trial that he didn’t want to discuss it, even with his family. And when his daughter Irene came to visit, all he wanted to do was sing Ukrainian folk songs. It was as if he was living in a state of shock—this can’t be happening to me. Hadn’t the court, and Israel, already found him guilty? So why be concerned if things weren’t going well? At times, he seemed depressed. At times, as happy as a child with a new toy.

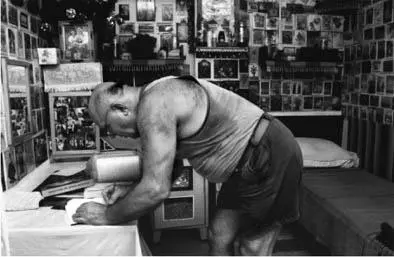

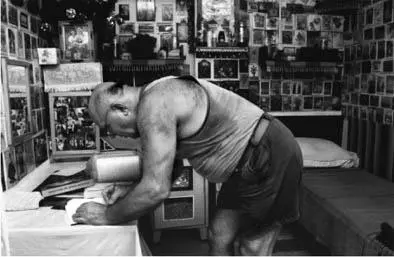

Most of the time, Demjanjuk lived in an optimistic world of his own creation. He decorated his cell walls with hundreds of letters, Christmas and Easter cards, pictures of Christ and the Virgin Mary, as if to insulate himself from the bad news of the courtroom.

Demjanjuk’s mood swings aside, the family had one thing going for it in its determination to get rid of John O’Connor. John Demjanjuk had never been an assertive man. He had always relied on his wife, Vera, to make the big decisions, and sometimes the small ones as well. Because he was passive by nature—not exactly the image of Ivan the Terrible—he had allowed his family to pick both lead attorneys, John Martin for the denaturalization trial and Mark O’Connor for the deportation hearing and the Jerusalem trial. If the family ganged up on him now, he would listen.

John Demjanjuk signed two blank pieces of paper the family gave him, either suspecting or knowing why. With the help of Sheftel, the family then drafted a letter above each signature. In one, Demjanjuk notified the court that he intended to fire O’Connor, asking for a trial extension to prepare for his defense with his new lead attorney. In the other, he told O’Connor he was finished.

“I am totally dissatisfied with your conduct of my defense, your conduct with my family, and your conduct with defense funds,” Demjanjuk wrote O’Connor. “These concerns of mine have been stated to you once and again previously…. Consequently, this is to notify you that you are being discharged immediately.”

• • •

Mark O’Connor was not happy about being sacked. His list of gripes against Sheftel sounded like Sheftel’s own list against O’Connor: not preparing for cross-examinations, trying to poison the Demjanjuk family against him, posing as the “savior” of John Demjanjuk, hogging media attention, making legal moves behind his back, and using the trial to boost his legal career.

O’Connor added three more gripes that were not on his co-counsel’s list. Sheftel was burned out and no longer capable of defending Demjanjuk because the rejection he experienced from his fellow countrymen had broken him. Furthermore, Sheftel was conspiring with the enemy—the prosecution—to get rid of O’Connor. And finally, Sheftel was a closet hypocrite, telling the Demjanjuk family that he supported them and would fight for them while in his heart he considered them to be anti-Semitic goyim.

O’Connor wrote Judge Levin a three-page letter accusing Sheftel of brainwashing the Demjanjuk family into getting him fired. “Mr. Sheftel convinced them to pressure the accused into signing two letters, backdated to June 30, 1987, removing his lead counsel from the case,” O’Connor wrote. “Mr. Demjanjuk had confided in me in prison that, although he desires my representation in the case, he must follow the direction of the family.”

O’Connor went on to warn the court of impending disaster if it accepted Sheftel as the new lead defense counsel. “Since Mr. Sheftel has refused for weeks to coordinate any trial preparation with me and visited the defense office in Jerusalem solely for the purpose of removing additional defense documents, he is totally unprepared to proceed.”

Then O’Connor tendered his resignation.

But it wasn’t quite that simple. “The decision to release the counsel is in our hands,” Judge Levin said in a special hearing on who would be in and who would be out. “We can accept it, and we can refuse to accept it, especially if it is contingent on postponing the rest of the trial. ”

Читать дальше