The Colt Single-Action Army Revolver was the first Colt pistol to accept center-fire cartridges. To this point, most Colt revolvers used percussion caps; powder and ball would be loaded down the front of the cylinder, with the percussion cap set on the other end. But the Smith & Wesson Model 3 started a revolution when it was introduced in 1869. The S & W revolver fired .44-caliber metal cartridges, greatly simplifying loading. All three parts of the ammunition—bullet, powder, primer—were married together in a container that could be easily carried and inserted into the weapon under even the worst conditions. Smith & Wesson wasn’t the first to use metal cartridges, and paper cartridges had been around since the beginning of time, or at least the early days of guns. But their system was reliable and efficient. It worked better than many of their predecessors. Just as important, it came at a time when people needed weapons that could fire multiple shots and be quickly reloaded. The U.S. Army put in an order, and the future of handguns was set.

The Russians had actually gotten their hands on the S & W Model 1 first, and in fact the Russian Imperial Government made several suggestions that improved the weapon. Their involvement almost ended up being a financial disaster for Smith & Wesson when disputes rose over payments due. The company persevered, and its handguns remained the chief American alternative to Colts for going on one hundred years. Times have changed, but in a lot of ways they’re still the Ford and Chevy of handheld armament.

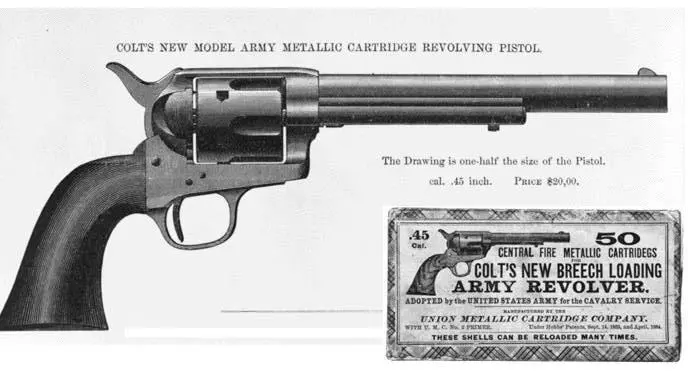

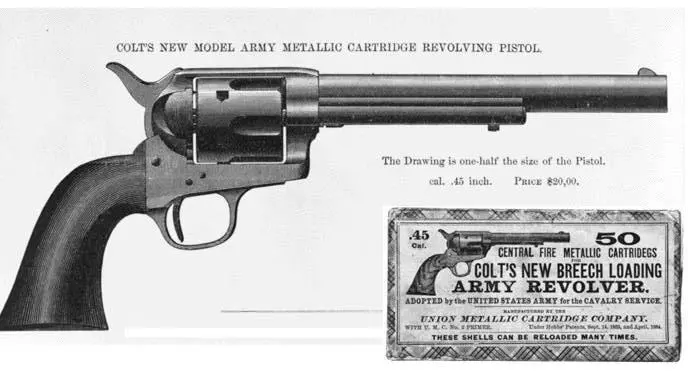

There’s nothing like a little competition to spur the creative juices. Colt’s weapon was a definite improvement on its own earlier designs, and the new ammo made it easier to use. The pistol was an immediate best-seller. As you can tell from the name, the weapon was designed for the Army, which was holding trials for a new sidearm contract. The government put in a large order, and the gun continued to be a military standard for two decades. Civilian models and a host of variations quickly followed. While the Army’s Colts were chambered for .45 caliber, the Colt Frontier used .44–40.

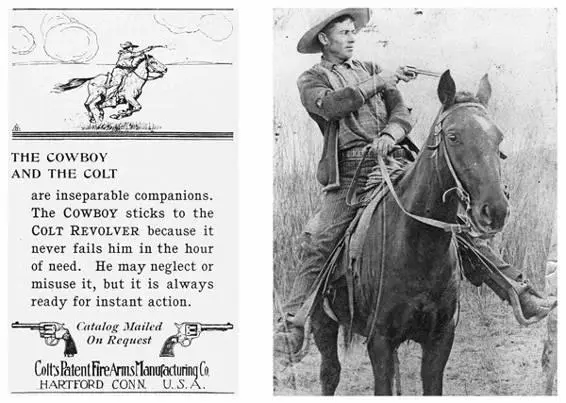

Lawmen loved the Single-Action Army. Cowboys and ranchers did, too. But it was the heroes and desperadoes who made the gun not just a legend, but part of the American identity. Buffalo Bill Cody, John Wesley Hardin, Judge Roy Bean, Wild Bill Hickok, Doc Holliday, Wyatt Earp, Pat Garrett, Billy the Kid, the Dalton Boys… you can’t hardly mention one of those names and not see a Colt in their hand.

And I don’t suppose you can talk about the Peacemaker without throwing at least one story of ne’er-do-wells and bank robbers into the mix.

I’ve always been partial to the tales surrounding Butch and Sundance myself. The outlaws Butch Cassidy (legal name: Robert LeRoy Parker) and the Sundance Kid (legal name: Harry Longbaugh) were big fans of the Colt Single-Action Army. Though they were both highly skilled shooters, they claimed to take great pains not to kill people during their legendary bank and train heists in the 1890s with their Wild Bunch Gang, also known as the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang.

An American icon: the 1873 Colt Army .45 revolver.

Library of Congress

According to one account, during their final exile in Bolivia, they put on an exhibition of fast drawing and fast shooting for a friend visiting from the States.

“Let’s show him, Kid,” said Butch.

“Let’s go, Butch,” said the Sundance Kid, who spun the cylinder of his six-shooter and jumped up.

The pair grabbed some empty bottles, went outside, and started throwing them high in the air, firing from a crouch.

“I never saw anything like it,” said their friend. “I never saw two guns drawn faster and I was with men skilled in firearms all my life. Before I knew it the Colts were in their hands and they were shooting. The four bottles crashed in splinters. They repeated this trick several times. Sometimes Butch missed but the Kid always hit the falling targets.”

Another time, Butch explained his preference for the Colt Single-Action Army: “It has a long and heavy barrel and can be used as a weapon. I’d rather crack a messenger across the nose than kill him. All the messenger has is a bump on the head. Hell, it isn’t his money anyway.”

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Western frontier began filling up with a motley cast of characters: miners, trappers, buffalo hunters, cattle rustlers, gamblers, outlaws, opportunists. In the midst of such company—and with the law still an irregular presence—you were well served to know your way around a gun. Clint Eastwood–style, one-on-one, fast-draw gun duels weren’t that common in the Old West, though you wouldn’t know it from Hollywood movies and TV shows. There were plenty of drunken shoot-outs, lots of which occurred in saloons, plus many ambush killings and cowardly shots in the back, but the number of classic “High Noon” gun showdowns was surprisingly few.

The exceptions to this rule are what we’re after. One of the best-known was the “Hickok-Tutt Gunfight,” which took place on the town square of Springfield, Missouri, on July 21, 1865, between Wild Bill Hickok and Davis Tutt. They’re still talking about it in Springfield, and quite a few other places as well.

This was the Super Bowl of shoot-outs, featuring a man who would become the dominant “gun celebrity” of his era, and an angry contender who’d once been his friend and business partner. The cause was a highly personal dispute over money and women. It featured a long buildup, hot emotions, and a crowd of spectators on the town square. All that was missing were hot dog vendors, sponsorship deals, and a halftime show.

The star of the showdown was Wild Bill. Not yet famous as the most skilled gunman of his time, Hickok had been a frontier scout and courier during the Indian and Civil Wars, a town marshal, U.S. deputy marshal, and a county sheriff. George Armstrong Custer said Hickok was a “strange character, just the one which a novelist might gloat over.”

And he looked the part. “He was a broad-shouldered, deep-chested, narrow-waisted fellow, over 6 feet tall, with broad features, high cheekbones and forehead, firm chin and aquiline nose,” wrote author Joseph G. Rosa, a Western historian and modern-day authority on Hickok. “His sensuous-looking mouth was surmounted by a straw-colored moustache, and his auburn hair was worn shoulder length, Plains style. But it was his blue-gray eyes that dominated his features. Normally friendly and expressive, his eyes, old-timers recalled, became hypnotically cold and bored into one when he was angry.”

The tussle was still a few years before the Peacemaker was invented, and Hickok wore an ivory-handled version of Colt’s 1851 Navy revolver, a cap and ball weapon that fired five .36-caliber rounds. It’s called Navy because of the size of the bullets, but don’t let that fool you. While the caliber was specified by the Navy and there was a Navy contract to make the original purchase, the primary customers were landlubbers, civilian and military. The smaller caliber made the gun a bit lighter and easier to carry and work in a fight.

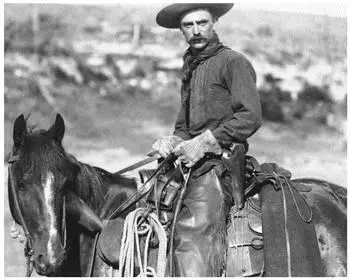

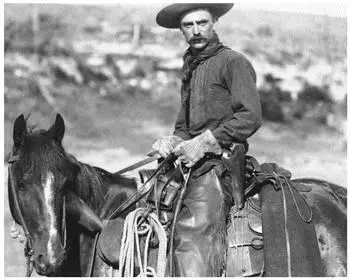

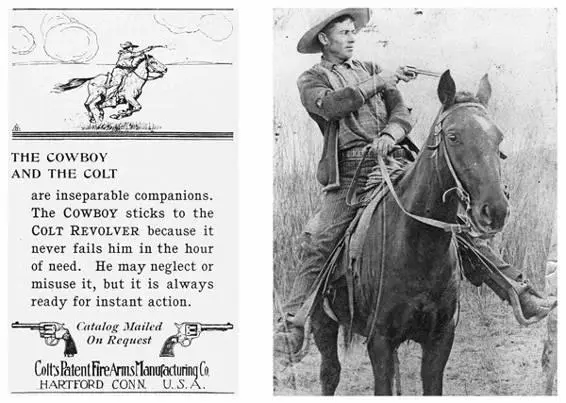

“Inseparable companions”: from hardworking ranchers (above) to outlaws (below right), Colt revolvers defined the Wild West.

Library of Congress

Hickok’s prowess with handguns became legendary on the American Plains after a Harper’s magazine article published in 1867 made him a national celebrity. While a great deal of mythology surrounds Will Bill, he was a hell of a shot, no doubt about it.

Читать дальше