The German army and economy could support a drive on Moscow. Though 560 miles east of the frontier, it was connected by a paved highway and railroads.

This would have still been a direct, frontal assault against the strength of the Red Army, but the ratio of force to space was so low in Russia that German mechanized forces could always find openings for indirect local advances into the Soviet rear. At the same time the widely spaced cities at which roads and railways converged offered the Germans alternative targets. While threatening one city north and another city south, they could actually strike at a third in between. But the Russians, not knowing which objective the Germans had chosen, would have to defend all three.

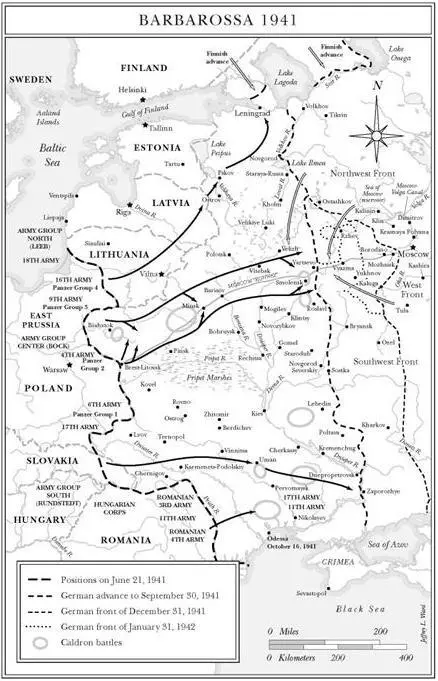

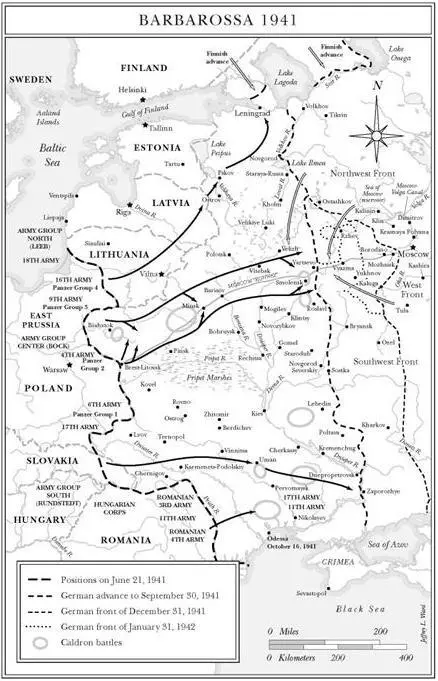

Hitler understood that he could not defeat the entire Red Army all at once. But he hoped to solve the problem by committing two of his four panzer groups, under Heinz Guderian and Hermann Hoth, to Army Group Center, commanded by Fedor von Bock, with the aim of destroying Red Army forces in front of Moscow in a series of giant encirclements — Kesselschlachten, or caldron battles. The Russians, to his thinking, could be eliminated in place.

Army Group Center was to attack just north of the Pripet Marshes, a huge swampy region 220 miles wide and 120 miles deep beginning some 170 miles east of Warsaw that effectively divided the front in half. Bock’s armies, led by the panzers, were to advance from East Prussia and the German-Russian frontier along the Bug River to Smolensk.

Army Group North under Wilhelm von Leeb, with one panzer group under Erich Hoepner, was to drive from East Prussia through the Baltic states to Leningrad.

Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South, with the last panzer group under Ewald von Kleist, was to thrust south of the Pripet Marshes toward the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, 300 airline miles from the jump-off points along and below the Bug, then drive to the industrial Donetz river basin, 430 miles southeast of Kiev.

The first great encirclement was to be in Army Group Center around Bialystok, fewer than sixty miles east of the German-Soviet boundary in Poland, the other around Minsk, 180 miles farther east. The two panzer groups were then to press on to Smolensk, 200 miles beyond Minsk, and bring about a third Kesselschlacht. After that, Hitler planned to shift the two panzer groups north to help capture Leningrad.

Only after Leningrad was seized, according to his directive of December 18, 1940, ordering Barbarossa, the German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941, “are further offensive operations to be initiated with the objective of occupying the important center of communications and of armaments manufacture, Moscow.”

Hitler, however, showed his intention of gaining all three objectives by directing that, when the caldron battles were completed (and Leningrad presumably taken), pursuit was to proceed not only toward Moscow but also into Ukraine to seize the Donetz basin.

In summary, Hitler’s original directive required massive strikes deep into the Soviet Union in three directions by three army groups, followed by a shift of half the army’s armor 400 miles north to capture Leningrad, then a return of this armor to press on Moscow, while Army Group South continued to drive into Ukraine, over 700 miles from the German-Soviet frontier.

This was impossible. In the event, Hitler made the task worse because he seized an opportunistic chance to destroy a number of armies in the Ukraine around Kiev and abandoned his original strategy. Once the caldron battles were completed in Army Group Center, he sent only one panzer group north toward Leningrad, and ordered the other south to help seal the enemy into a pocket east of Kiev.

Army Group North did not have enough strength to seize Leningrad. By the time the diverted panzers got back on the road to Moscow, the rainy season had set in, then the Russian winter. As a consequence the strike for Moscow failed as well. With insufficient armor remaining in the south, the effort to seize all of Ukraine and open a path to the oil of the Caucasus also collapsed.

Hitler, by trying for too much, and then altering his priorities by sending a panzer group from the center into the Ukraine, failed everywhere. These failures meant Germany had lost the war. By December 1941, there was no hope of anything better than a negotiated peace. This Hitler refused to consider.

Hitler’s plan rested on two false assumptions. The first was that he would have time enough (even without the shift of panzers to the Ukraine) to switch armor to the north then back to the center in time to win a decisive victory before the rains and snows of autumn. Distances were simply too great, Russian roads and climate too poor, and Red Army resistance too intense for such a plan to have had any hope of success. As Guderian summarized the campaign to his wife on December 10, 1941, “The enemy, the size of the country, and the foulness of the weather were all grossly underestimated.”

The second great mistaken assumption was that after destroying the Red Army in caldron battles, Stalin would be unable to create any more armies. That is, once the Kesselschlachten were over, the Soviet Union would collapse, and the Germans could occupy the rest of the country at their leisure and without resistance. But Hitler did not count on the resilience of Soviet leadership and the willingness of the Russian people to defend their homeland. Moreover, Hitler’s ally Japan refused to attack Siberia, allowing Stalin to release a quarter of a million soldiers to rush west to fight the Germans at a crucial moment.

Although Moscow was the only target the Germans might have gained in 1941, neither Brauchitsch nor Halder was willing to confront Hitler on the point. They hoped, when the time came, they could convince him to keep the panzers in the middle, change his ideas about shifting them, and continue the drive on Moscow. They were wrong.

The concept of caldron battles appears on the surface to be a highly dangerous strategy—to rely on the enemy conveniently allowing German forces to wrap themselves around great concentrations of his troops, and forcing them to surrender. However, Stalin made this a feasible strategy because he lined up the vast majority of his forces along the frontier. Consequently, German breakthroughs at a few points would permit German forces to sweep past and behind large segments of the Red Army, blocking their retreat and creating a caldron.

Such encirclements were a part of German doctrine, advocated by German theorists as far back as Karl Clausewitz in the early nineteenth century. They modeled their ideas on Hannibal’s classic destruction of a Roman army at Cannae by encirclement in 216 B.C. The greatest German victory up to the 1940 campaign in the west had been another—the encirclement of a Russian army at Tannenburg in East Prussia in August 1914.

The Russian campaign was not to be a repetition of the blitzkrieg of 1940 in the west. Rather it was to be a series of classic encirclements, accelerated only by using the panzers to swing around the enemy flanks to create caldrons.

In most wars, the inherent strength of the belligerents becomes more and more important once past the initial or opening campaign or phase. If a power is unable to achieve a decision with its original force, then long-term factors generally decide the war. Superior power exerted over time to wear down an opponent is called attrition. This is the single greatest danger that a weaker belligerent encounters.

This is what Adolf Hitler faced. The Soviet Union’s resources were immense compared to Germany’s. Its great size forced an enormous dispersal of German military strength. Its population was more than twice Germany’s. It had unlimited quantities of oil, minerals, and power. Soviet war production over time would outstrip German production. In addition, the Soviet Union could tap the resources of the rest of the world, especially the United States, because the Allies controlled the seas and could deliver goods by way of Iran.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)