More than half the Germans who landed on Crete died or were wounded. Altogether 11th Air Corps lost 6,000 men, two-thirds dead, the rest wounded. The highest losses were in the most battle-tested, best-trained outfits. Student said after the war that “the Fuehrer was very upset by the heavy losses suffered by the parachute units, and came to the conclusion that their surprise value had passed. After that he often said to me, ‘The day of parachute troops is over.’”

General Halder’s glib hope that the capture of Crete would lead to easier supply for North Africa remained the mirage it had always been. The main Axis supply line ran as before past Malta.

7 ROMMEL’S UNAPPRECIATED GIFT

ON THE MORNING OF FEBRUARY 11, 1941, GENERAL ERWIN ROMMEL, COMMANDER of the as yet nonexistent Africa Corps, along with Adolf Hitler’s adjutant, Lieutenant Colonel Rudolf Schmundt, flew in a Heinkel 111 bomber from Catania, Sicily, to Tripoli. Rommel wanted to check out the situation in Libya before the leading elements of his corps arrived.

At Catania he had asked the commander of the German 10th Air Corps, General Hans Geisler, to bomb Benghazi and British columns reported nearby. Geisler protested that he couldn’t do that, because many Italian officers and officials owned homes at Benghazi and Italian authorities didn’t want the place hit. Exasperated, Rommel queried Hitler’s headquarters and got quick approval for the Luftwaffe to strike.

At Tripoli, the Italian officers were packing their bags for imminent departure, and saw little hope of holding Sirte, some 230 miles east of Tripoli, where Rommel wanted to set up a defensive line. Rommel decided to take command himself at the front, and that afternoon flew off with Schmundt in the Heinkel to Sirte.

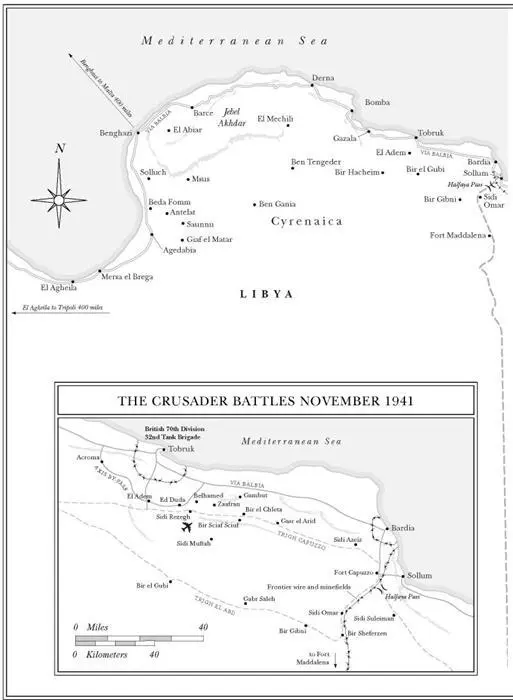

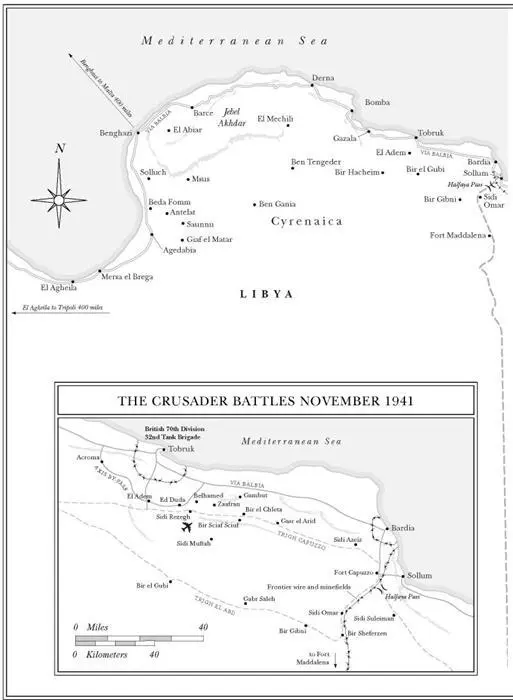

Rommel’s first view of Africa was sobering. The terrain alternated between sandy wastes and featureless hills. Through it all, he wrote, the only paved road in Libya, “the Via Balbia, stretched away like a black thread through the desolate landscape, in which neither tree nor bush could be seen as far as the eye could reach.”

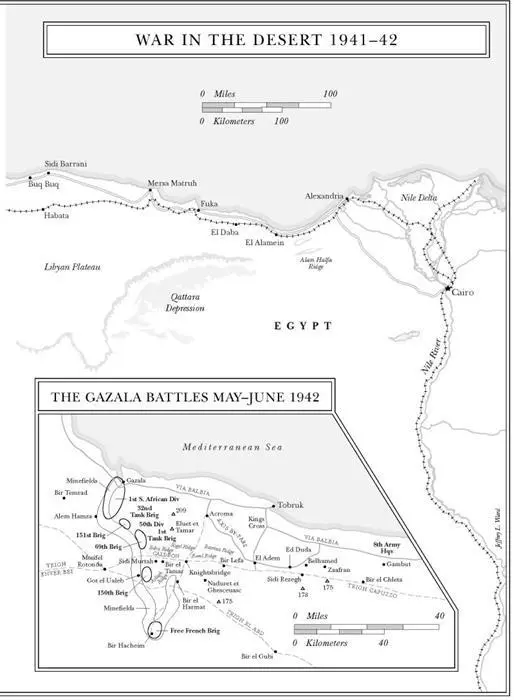

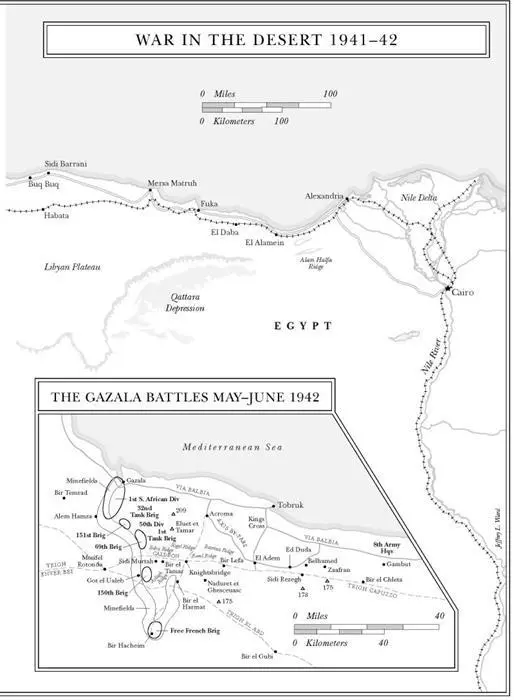

At Sirte only a single Italian regiment was on guard. The closest British troops were at El Agheila, 180 miles farther east. They were stopped there, not by the Italians, but because they were at the end of an extremely long supply line (630 miles back to Mersa Matruh and the British railhead), and because the Middle East command was transferring many British troops to Greece.

The remaining Italian troops in Libya were 200 miles west of Sirte around Tripoli. At Rommel’s insistence, leading elements of three Italian divisions there began moving toward Sirte on February 14.

On the same day the first German troops—the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion and the antitank battalion of 5th Light Division—arrived at Tripoli on a transport. Rommel insisted, despite danger of air attack, on unloading the ship by searchlight throughout the night. The next morning the two German outfits, in their new tropical uniforms, paraded through Tripoli, then moved off to Sirte, arriving twenty-six hours later.

Rommel had already grasped the essence of the war in Libya and Egypt: everything depended upon mobility.

“In the North African desert,” he wrote, “nonmotorized troops are of practically no value against a motorized enemy, since the enemy has the chance, in almost every position, of making the action fluid by a turning movement around the south.”

This was why the Italians had been beaten almost without a fight—they had moved largely on foot; the British were in vehicles. Nonmotorized forces could be used only in defensive positions, Rommel saw. Yet such positions were of little consequence, because enemy motorized units could surround them and force them to surrender, or bypass them. In other words, foot soldiers in the desert had no impact beyond the reach of their guns.

Rommel discerned that desert warfare was strangely similar to war at sea. Motorized equipment could move at will over it and usually in any direction, much as ships could move over oceans. Rommel described the similarity thus: “Whoever has the weapons with the greatest range has the longest arm, exactly as at sea. Whoever has the greater mobility … can by swift action compel his opponent to act according to his wishes.”

The Italians were discouraged, and little interested in challenging the British, while Rommel had only two battalions of 5th Light Division. The whole division couldn’t get there until mid-April, and Rommel’s main striking force, 15th Panzer Division, would take till the end of May to assemble.

Rommel knew that Hitler’s interest in North Africa was limited to helping the Italians hold Libya. Otherwise, he would have provided more adequate forces. However, Rommel, who had won Germany’s highest decoration for valor in World War I (the Pour le Mérite, or “Blue Max”), was a resourceful and determined officer, not deterred by obstacles. No one knew it at the moment, but Erwin Rommel was one of the greatest generals of modern times. Moreover, he possessed a burning ambition to succeed.

Rommel decided to use the modest tools on hand to strike a surprise blow at the British, who were somewhat complacently sitting between El Agheila and Agedabia, sixty miles farther northeast. General O’Connor had gone back to Egypt, succeeded by Lieutenant General Sir Philip Neame, who had little experience in desert warfare. General Wavell had replaced the experienced 7th Armored Division (the “Desert Rats”) with half of the raw 2nd Armored Division, just arrived from England, while the other half had been sent to Greece. He had also replaced the seasoned 6th Australian Division with the 9th Australian Division, but, because of supply difficulties, part of the division had been retained at Tobruk, 280 air miles northeast.

Wavell thought the few Italians still in Tripolitania could be disregarded. And though he’d received intelligence reports that the Germans were sending “one armored brigade,” Wavell concluded, on March 2, 1941, “I do not think that with this force the enemy will attempt to recover Benghazi.”

That was a reasonable conclusion. No ordinary general would attack with such a small force. But Rommel was not an ordinary general.

Since none of his tanks had arrived, Rommel got a workshop near Tripoli to produce large numbers of dummy tanks, which he mounted on Volkswagens. These small vehicles served as the jeeps of the German army. They looked deceptively like tanks—at least to RAF reconnaissance pilots—and gave the British command pause.

Meantime Rommel moved up the two German battalions and his dummy tanks to Mugtaa, twenty miles west of El Agheila. Elements of two Italian divisions, the Brescia and Pavia, followed, along with the Ariete, Italy’s only armored division in Africa, which had just eighty tanks, most of them obsolete light models.

General Neame, suspicious of the buildup at Mugtaa, modest as it was, moved the main British body back to Agedabia, seventy miles northeast, leaving only a small holding force at El Agheila.

On March 11, the 5th Panzer Regiment of 5th Light Division—the “armored brigade” Wavell had heard about—arrived at Tripoli. This regiment, the only armored force that Africa Corps was to get until the 15th Panzer Division arrived, had 120 tanks, half of them medium Mark IIIs and IVs, the rest light tanks with only a limited combat role. Although 5th Light was not a panzer division, it had the normal complement of tanks of a panzer division in 1941. This total, however, was only a little more than half the number Rommel had commanded in his 7th Panzer Division in the 1940 campaign. After the French campaign, Hitler doubled the number of panzer divisions, but gave each division fewer tanks.

Читать дальше

![Джонатан Димблби - Barbarossa - How Hitler Lost the War [calibre]](/books/385421/dzhonatan-dimblbi-barbarossa-how-hitler-lost-the-w-thumb.webp)