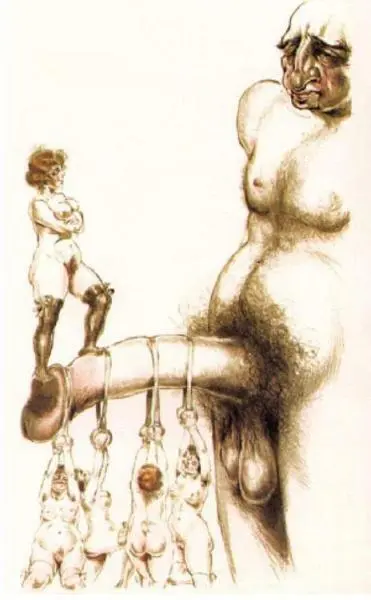

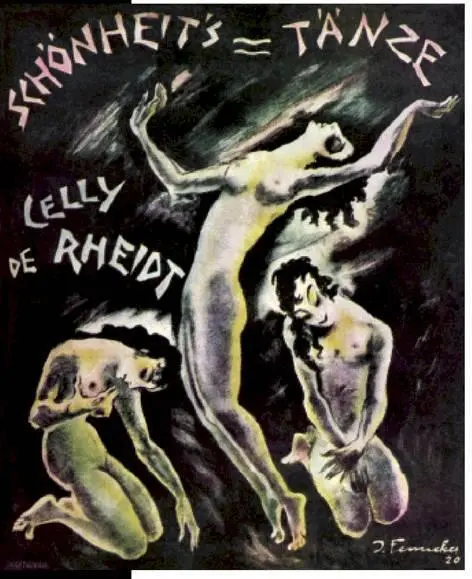

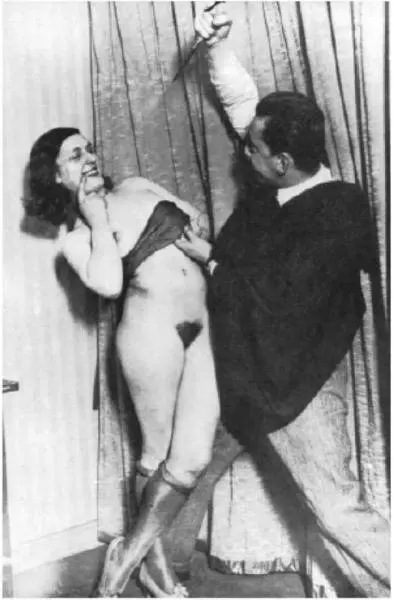

Max Liebermann, Erotic Grotesques , 1920

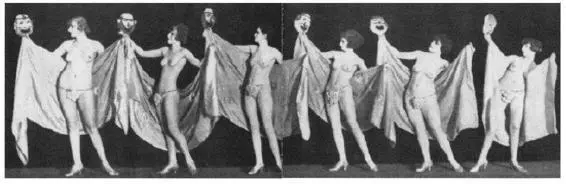

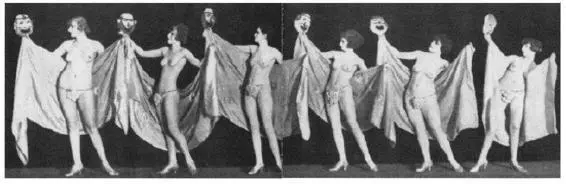

CELLY DE RHEIDT DANCE TROUPE IN A TYPICAL EVENING: “THE DANCE OF BEAUTY” (1923)

Harry Seveloh, the husband of the lead dancer, delivers a short introduction to the program. He enthuses that Berlin high society has now grown mature enough to enjoy the sights of naked female performers without lewd, sensual stimulation. The spectator’s appreciation of the girls’ exposed beauty should be of a purely intellectual or aesthetic nature.

Scattered applause from the mature audience. The curtain is drawn, exposing a tiny stage.

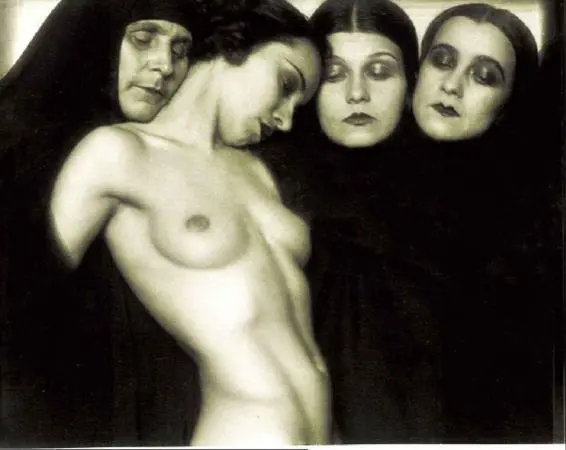

Rudolf Koppitz, 1925

Oddly enough, Kander and Ebb got this part right. The literary and political cabarets, because of their high artistic content and celebrity casting, received substantial print coverage, which survived (in bits and drabs) to be analyzed and deconstructed by post-World War II historians. The more popular erotic cabarets hardly merited notice, except in the downtrodden Galante monthlies.

One sensational production mounted at the Black Cat Cabaret, “The Dance of Beauty,” achieved widespread notoriety due to its novelty during the Inflation and the legal problems that dogged its creators. Described in remarkable detail by Hirschfeld, Paul Markus (ʺPEMʺ), and several Berlin newspaper reporters, the performance revealed a relatively early attempt to stitch the naughty cabaret impulse to the protective frame of Ausdruckstanz (Expression Dance).

Celly De Rheidt’s brazen troupe was forced to disband shortly after this engagement. Her entrepreneurial husband, Seveloh, a former army lieutenant, was penalized 1500 Inflation marks, which he managed to delay paying until the following summer when the fine’s actual dollar value approached a near-zero decimal. Celly divorced him, remarried in Vienna, and settled down to be an upstanding Hausfrau, never to heard from again.

Scene from the Haller-Revue

Gypsy violin music slowly ushers in a line of female artistes.

A waltz, danced by Celly de Rheidt and her ballet group, wearing short transparent dance-dresses, commences. A violet light illuminates them as they float across the dance floor, slowly in the beginning, then in a furious pace. Their bodies freeze, silhouetted against the background of the closing curtain.

A short violin interlude. Again the Girls appear and dance a wild bacchanal under a reddish-purple light. They wear transparent dance-dresses that expose one breast. The wild twirls are followed by a brightly illuminated dance scene: a spring serenade with the music of Lecombe, performed by Celly and a young attractive dancer. Each wears a short, fluttering chiffon skirt below a nude torso. The girl suddenly collapses. She is startled out of her dream state and begins to leap rapturously in a flower movement. Her body sways outward, as she lifts her breasts to the warm, life-giving sun.

The stage darkens as a circle of barefoot girls in peasant dresses rush forward to execute a vibrant Hungarian folk dance.

An erotic pantomime, the “Opium Slumber,” ensues in quick succession. It begins with the shadow of a Chinaman smoking wanly on an opium pipe. After a few minutes, an evil femme fatale appears and seductively enslaves him to be a victim for her mélange of sadistically lewd games. The club spectators watch this with a special intensity.

This is followed by a carnal “Bullfight,” performed to the clicking of castanets. Celly, the female matador, disrobes with exquisite deliberation and uses her diaphanous garb to sexually torment and subjugate the hapless beast. The dance concludes with the defeated bull lying supine next to the high heels of the triumphant—and now naked—matador.

After the Black Cat affair, naturally, no Berlin cabaret was stupid enough to flaunt its fleshy wares as high art in the face of the authorities or, if it did, forget to compensate the local Polenta for their impeccable critical faculties.

Foreign tourist guides, true to their calling, championed the Kabarettwelt’ s indecent rep. Jägerstrasse, the home to 14 or 15 Nachtlokals , was publicized as Berlin’s hothouse citadel of forbidden sights. Yet, around 1927, a natural downturn occurred. The dark hedonism of the erotic cabaret could be explored in other, more comfortable and accessible surroundings: in ritzy dinner clubs, private Dielen , a few showy restaurants, the “Pleasure-Palaces,” even on an evening’s Bummel of the Kudamm.

Most “Golden Age” Berliners patronized the non-literary cabarets for their ineffable atmospheres, the cynical mood ( Berliner Stimmung ) that enveloped the stale, smoky air, and only occasionally for the overpriced intoxicants and nude tableaux. Usually, the cabaret conférenciers, or Masters of Ceremonies, were the chief draw. These tuxedoed wits did not exist anywhere else.

While Friedrichstadt Lokal producers experimented with endless sexual and thematic innovations, one out-landish idea succeeded. A malicious conférencier, Erwin Lowinsky, known in the trade as “Elow,” rented the for-mer Weisse Maus cabaret on Jägerstrasse from its new lesbian owners. Running only on Café Monbijou’s dark night, Monday, Elow called his enterprise the “Cabaret of the Nameless.” Instead of hiring professional entertainers, Elow did just the opposite; his stage was open only to amateur performers, 15 per evening.

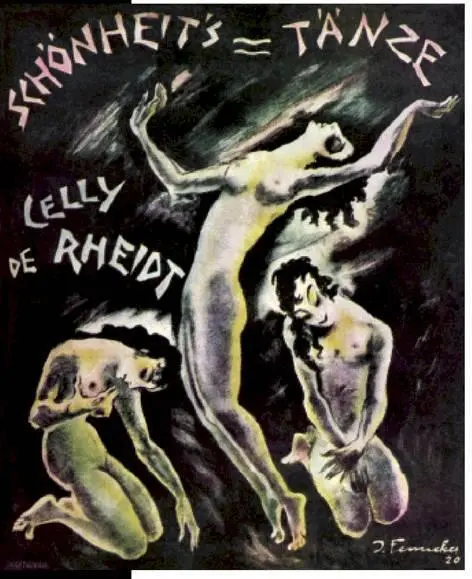

Poster for the Celly de Rheidt Ballet Beauty Dances

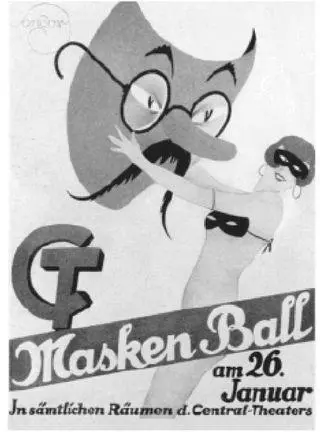

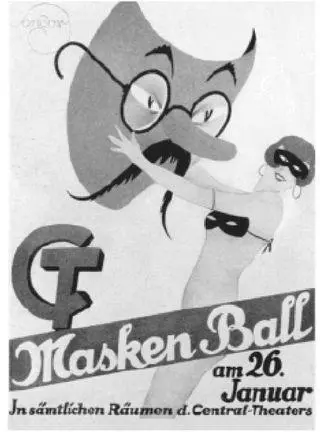

Comic “Jack the Ripper” scene in a cabaret, 1926

Elow chose for his off-night cabaret the most thoroughly talentless types he could possibly find, including—for the greater delight of his demented public—utterly delusional and rapturous sickies. Berlin intellectuals compared the milieu of the Nameless to the Roman Coliseum where Christians were savagely martyred, to neighborhood bullfighting rings in Mexico City, and to the execution of criminals by guillotine on Paris’ sidestreets.

The menacing cadence of an Inca sacrificial ceremony is pounded out by the orchestra. On a mountain plateau, a bevy of pearl-necklaced, naked virgins are forced to participate in the ritual murder of their sisters and then given drugs by a High Priest so they may delight in erotic worship with the nubile corpses.

Finally, a fully orchestrated Spanish mystery play, based on Calderon’s The Nun , is enacted. A cello solo establishes the somber mood. Then a procession of nuns and monks, led by a bishop, moves through the audience to the stage, which is arranged like the interior of a church and lit in dark purple columns. The procession is accompanied by the sound of harpsichord, violins, and the cello. A trembling young Sister, played by the histrionic Celly, is brought before the altar of the inquisitorial court. The Father declares her unchaste, worthless. Despite her mad pleas, the errant “Daughter of Christ” is mercilessly expelled from her Order. Before a statute of Mary, the distraught teenager rips off her habit and begs for divine intervention. The Holy Virgin magically steps forth, passionately kisses the Nun, fondles each of her breasts with a slow, icy touch, and then presents the Sister with a silver crucifix—all before the eyes of a stunned clergy. Lights out!

Читать дальше