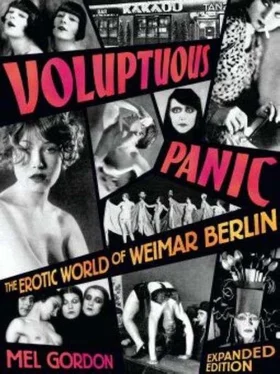

Fortunately there were books for the uninformed. Directories of nocturnal Berlin (in adventurous straight, S&M, gay, lesbian, or nudist versions) could be had at any train station, hotel lobby, or downtown kiosk. Foreigners and provincials alike could plot out, with a thumb-flip, where or where not they were wanted, calculate what to expect and spend, and fantasize how their dream Bummel or session might unfold. These lurid Baedekers of the night were indispensable pilots for lost souls.

Not every Berliner—or tourist—was swept away in the Weimar sex-rush. But the aggregate who participated in some commercial aspect of the Kietz , especially during the Inflation or the approaching depression, was extraordinarily high. Probably 20 to 25 percent of adult Berlin dabbled in the midnight amusements in the year before Hitler was anointed Reichschancellor. While newcomers thought the erotic madness was, more or less, a function of the uncertain economic times, Berliners themselves jokingly blamed it on their amphetamine-like air (that Berliner Luft ), which many swore kept their hearts racing at night and then thoroughly revitalized them for the morning commute.

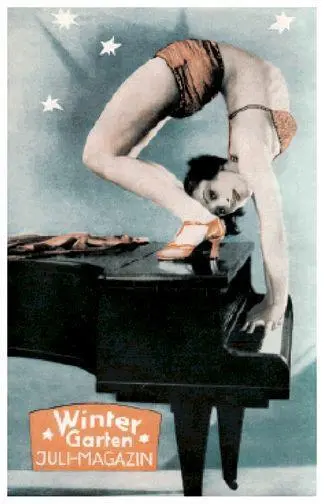

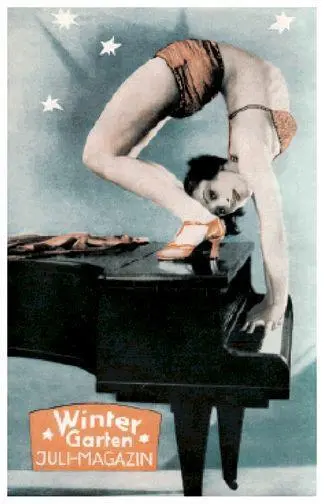

Poster for The Crooked Mirror cabaret, 1928

Poisonous fumes or no, the Sittengeschichten scholars of the time understood how the whore milieu permeated workaday Berlin. Advertising, music, mass-market periodicals, clothing styles, stage interpretations of Shakespeare and Schiller, high literature, dining arrangements in restaurants, and election propaganda were all indelibly stamped with this new image of female sexuality and the independent woman. In the mid-Twenties, it acquired a name: Girlkultur .

An abiding brainstorm of Flo Ziegfeld, the eponymous American producer, “Girl-Culture” redefined the psychology and bodily form of the desirable female. In heavily-promoted publicity campaigns and on the stage of his New York Follies, Ziegfeld advanced and constantly reshaped this modern fantasy creature. She was urbane, slim, not much interested in children, socially irreverent, leggy, charmingly vain, and a sexual predator. The Ziegfeld Girl had all the basic physical attractions of the Parisian Flirt, but her gold-digging motivations were refreshingly undisguised and externalized.

The American Flapper persona fit snugly into the unsentimental machine-age Zeitgeist . It universalized femme-fatalism. Sex appeal was no longer a mysterious inborn construct but a purchasable commodity, available to the entire female-of-the-species. And seduction could be played out for better rewards than bourgeois marriage—and far longer—when its ultimate goals were money (or diamonds, gold jewelry, furs, penthouses) and emotional dominance.

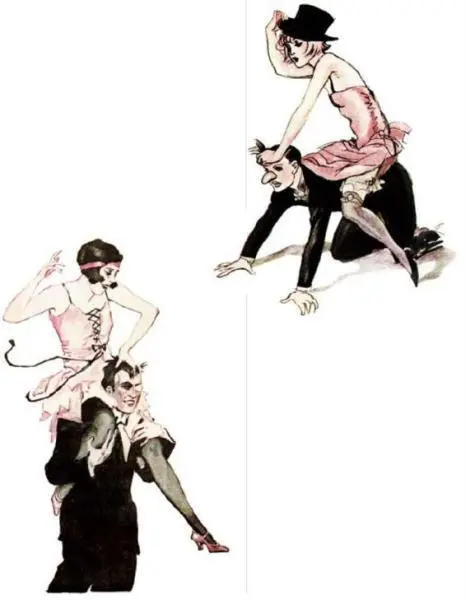

Berliners, far more than Manhattanites, adapted Ziegfeld’s provocative concept to their mentality and lifestyle. It glamorized and extended the war between the sexes. Women and men each possessed something the other passionately desired in the big-city tango. In fact, Berlin’s professional Beinls were often looked upon as the heartfelt, unadorned subset of the New Woman. The dazzling sex cards they held were short-lived and not a danger to the gender status quo. The roles of good and bad women in Weimar had become reversed. Any Bubikopfed teen was a potential Lulu, or Nutte .

Heinz von Perckhammer, A Nachtlokal on the Friedrichstadt

Girl-Culture also referred to the precision chorus line, which Ziegfeld’s choreographers contrived from a blend of French Can-Can and the American fascination with Taylorist motion economy. Stunning Girl-Groups from Anglo-Saxon countries demonstrated synchronized kick displays that beat the hell out of the prewar Tangel-Tingel leg shows. Each angelic dancer, the identical duplicate of the other, resembled an interchangeable machine part or a blank-faced soldier in a Prussian army drill. Here, the New Woman was automated, made trainable, streamlined, remolded into a robotic doll. Both aspects of Girl-Culture—the Demonic Sex Object and the Rationalized Sex Object—enthralled and animated Berlin.

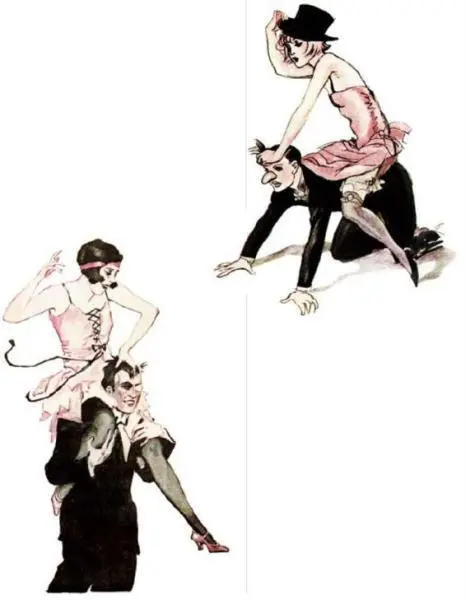

Walter Pantikow, Berliner Leben , 1928

The pairing or struggle between these modern archetypes largely replaced the old brunette/blonde conflict inside Berlin’s venerable theatre prosceniums. Male characters in sex farces and jazzy operettas no longer had to deal with the classic dilemma, the penis versus the heart. The ingenues-in-question were each beddable hellcats. Which succubi to wed or follow to Paris became the novel contentious denouement.

In Fritz Lang’s epic film, Metropolis (1927), where Berlin’s social and cultural conflicts were projected into a science-fantasy future, the theme of Girl-Culture was handled with recondite humor and a hokey melodramatic touch. One year later, Brecht and Weill bested the movie with their avant-garde musical, The Three-Penny Opera . By adding cynical dollops of Berliner Schnauze and restituating the Berliner erotic typology to Victorian London, the unlikely modernists perfected the titillating master narrative. Virtually the entire Berlin press corps hailed the brilliant rendering. The Marxist poet Brecht insisted, in his contrarian manner, that the play was a comic, left-wing indictment of capitalism, but the critics knew better. Three-Penny was Girl-Culture in song.

What Berlinerinnen felt about Girl-Culture is a contentious subject for feminist scholars. Interviews (that I conducted) with women who were teenagers and 20-year-olds in Weimar Berlin and a perusal of popular women’s magazines of the period indicate a high degree of personal satisfaction. Suddenly females from Wilhelmian families were accorded social and carnal opportunities that made them the envy of their older sisters. One woman called Girl-Culture sexual suffrage. Female novelists and Berlin’s feminists, as was their wont, were considerably more critical of the invented revolution.

Cabaret was, of course, the signature entertainment form of Weimar Berlin. Born in the backhalls and miniature variety-houses of fin-de-siècle Montmartre and Vienna, the cabaret melded lowly amusement genres to Bohemian sensibilities, in the service of a middleclass audience on the slum. In Berlin, the “tenth muse” unraveled, returning to its maverick roots: the brothel and concert-café.

Of the 150 Berlin commercial outlets that advertised cabaret revues, only a dozen or so were traditional cabarets in the Parisian mode: shows with alternating acts of musical comedy, poetry reading, topical monologues, torch songs, sleight-of-hand routines, dramatic sketches, and the like. In a sense, these were hip Music-Halls presented within an intimate restaurant setting. The evening’s mood in these houses shifted expeditiously, from laughter to tears to awe to artistic appreciation and finally back to laughter, with each succeeding act. In the standard Jägerstrasse Kabarett , however, there were only two moods: the bitterly sardonic and the heart-thumpingly erotic.

Читать дальше