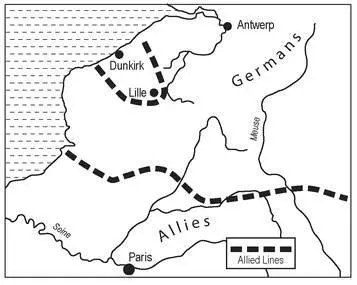

The French reaction was to do nothing. Even after Poland was invaded, there was no effort to add even the most rudimentary fortifications to the border that ran from the Ardennes to the Channel. Half of the French border was solidly fortified. The northern half, the route German armies had used almost every time they invaded France in the past thousand years, was left undefended. Eventually, the leaders of France justified stopping halfway by explaining that now they knew where the Germans had to attack since the Maginot Line was impregnable. Unfortunately for them, they were so right and so very wrong.

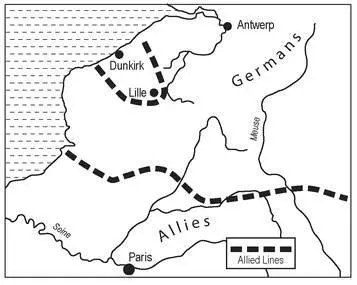

With half the border defenseless, the French and British agreed on a new strategy. When the Germans invaded Belgium, and only after they invaded, massive armies, waiting along the French border, would rush north and reinforce the Belgian army. The plan even worked. When the Sitzkrieg ended and the fighting between France and Germany began, the Nazis did attack northern Belgium; and like everyone expected, a day later the British Expeditionary Force and a substantial part of the French army hurried past the undefended French border and into defensive positions along Belgium’s waterways. While they did so, the Germans pressed only a little and mostly waited.

Once the British and French had committed dozens of divisions in Belgium, the Wehrmacht attacked through the virtually undefended Ardennes Forest. Undefended because the Maginot Line stopped short of it, and the French incorrectly assumed the forest was too dense for a major offensive to push through. They were wrong about it being impassable, and within weeks the main German offensive had reached the Channel. Hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers were now trapped in Belgium. About 300,000 were eventually evacuated from Dunkirk, but more than that were left surrounded in northern Belgium while the panzers poured over the undefended portions of the French border and tore through France. Exactly one month after the Ardennes attack, the Nazis occupied Paris.

The part of the Maginot Line that was completed worked; what few Nazi assaults were made along it from Germany failed. But once France fell, most of the defenders had to surrender. Their guns faced the wrong way and many of their families were in German hands. The few fortresses that held out were not even attacked. Bulldozers were used to simply cover the turrets, ventilation shafts, and entrances with yards of dirt that turned the underground defenses into tombs.

But by allowing politics to overcome military sense, the incredibly expensive fortification failed to be more than a trap for the men manning it. Had the national wealth spent on constructing the Maginot Line been spent on tanks, planes, and artillery, the French army would have been immeasurably stronger. But the postwar wealth of France was squandered on a defensive line that by being incomplete accomplished nothing.

Had France ignored the irrational objections of Belgium and completed the Maginot Line, it might well have fulfilled its purpose. If, in 1940, the German panzer spearheads had to fight through a completed Maginot Line, their losses would have been staggering. The Nazis might still have defeated France in a much longer war, or they might not have, as the Blitzkrieg would have had little effect on mutually supporting and highly fortified positions. France might even have survived long enough to learn how to fight a modern war or force yet another stalemate on her German invaders.

72. STOPPING SHORT OF VICTORY

Miracle by Mistake

1940

Blitzkrieg was smashing France. The Wehrmacht had sailed through the “impassable” Ardennes Forest and bypassed the Maginot Line. German panzer divisions had spearheaded a push to the Channel that had effectively cut the British forces off from the French army and was pushing them back to the coast. On May 24, 1940, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was deeply engaged with the German Second Army. On that same day, the foremost of Heinz Guderian’s panzer units were thirty miles from the port of Dunkirk. This put a substantial amount of Nazi armored and highly mobile units close to Dunkirk, the last continental channel port in Allied hands. The Nazis had more units near the port than almost all of the BEF combined. Worse yet, the BEF was totally engaged and could spare nothing to meet the threat in their rear. They were saved only because on that same day the order was received from Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt to the panzer divisions in Army Group A, which included all of the forces facing the BEF, to halt and re-form on the Lens to Gravelines canals. That move not only stopped Guderian from going for the port but relieved the pressure on the rest of the BEF as well. This order may well have lost Germany its last chance to force a peace on Britain.

The Dunkirk evacuation

There has since been a lot of speculation as to why the decision to halt the panzers was made. No one after the war was sure why this order was given. It certainly wasn’t because the armored units needed to stop. Diaries from the battle showed that the men and equipment were capable of continuing to attack, and they were frustrated at not being able to do so. Often speculation turns to the theory that Hermann Goering wanted the glory of giving the BEF its coup de grace to go to the Luftwaffe alone. Reichsmarschall Goering was also effectively the number two authority in the Nazi government and had Hitler’s ear, so he could easily have made such a demand.

This stop order came from the highest level and may have been influenced by Hitler’s desire to seek a quick peace with Britain to leave his entire army free to deal with Russia. Planning for the attack that actually occurred the next summer was already being developed. Allowing the BEF to escape, or at least surrender rather than be destroyed, may have been a ploy used by the Führer to encourage better relations with the British. At this point, he still had hopes of joining with his fellow English Aryans in his planned war against all Slavs and other untermenschen . Or perhaps it was ordered because Hitler had experienced the mud of Flanders first-hand in World War I and was afraid that the armored elite of his army would bog down and be of no use in finishing off France. What is certain is that the decision was not caused by any action taken by the Allies nor was it at all popular with the German general staff. Whatever the reason, this mistake may well have changed the entire course of World War II.

If Dunkirk had fallen, then there was no place for the BEF and associated Allied units to retreat from. The 338,000 men evacuated would have been lost or become prisoners. The bulk of the British officer corps and noncommissioned officers, who later formed the core of the British army fighting in North Africa and landing in Normandy, would have been lost.

One of the likely effects of such a loss on Britain would have been the collapse of civilian morale. If that happened, there was a high probability that Britain would have entered into the peace talks Hitler so desired. And in those talks the British empire might well have been represented by the less-determined Clement Attlee and not the then sea lord Winston Churchill. Churchill gained his premiership partially by riding the burst of confidence that came from the successful withdrawal of the BEF. If the bulk of the Royal Army had been lost, the more timid and conciliatory Attlee might well have accepted the premiership instead. In reality, Clement Attlee was offered the leadership of Britain, but he declined in Churchill’s favor. Since Hitler publicly stated that he thought of the British as being fellow Aryans, this might well have encouraged a peace agreement or at least a British openness to a negotiated peace that preserved their empire. Avoiding a two-front war was a tenet of German strategy. That doctrine combined with Hitler’s determination to attack communist Russia suggests that the terms the Führer might have offered Britain would certainly have been very generous.

Читать дальше