Here is how phlogiston seemed to work: Such chemicals as charcoal and sulfur were thought to be made almost completely of phlogiston. This was because when you burn them there is nothing left except a little ash, which was explained as the impurities in the phlogiston. After all, if you dephlogisticate a material that was made up mostly of some form of the heat itself, there will be little left behind.

Take another illustrative example: If one room was warm and the other cool and you opened a door between them, then the phlogiston, like any gas or liquid, would seek to balance itself between the two rooms. Phlogiston would flow into the cool room and out of the warm, phlogiston-filled room; and since it’s the essence of heat, it would raise the temperature of the cooler room and lower that in the warmer room. Eventually the amount of phlogiston would level out between the two rooms, and they would be the same temperature.

The remarkable thing about this amazing theory was that it seemed to have worked, and it had been used by eminent and respected early scientists for an entire century before it was finally proven wrong. It was not until science progressed to the point that researchers understood the fluid dynamics of the second example and Lavoisier explained the chemical changes that occurred in burning charcoal that the idea of phlogiston died out. This disproving was done by Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier at the end of the eighteenth century. He did this when he discovered oxygen and determined the actual chemical reactions that occur during combustion. Phlogiston theory was perhaps the most persistent, widespread, and totally wrong mistake made by scientists all through the age when science, as we know it today, was developed.

39. ALL COURAGE AND NO PLAN

Culloden

1746

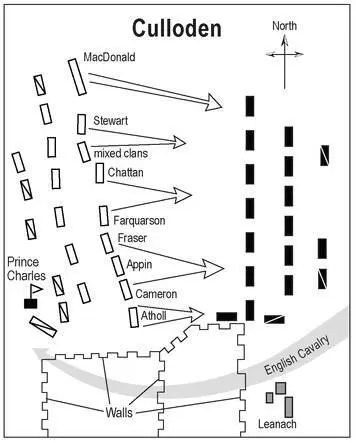

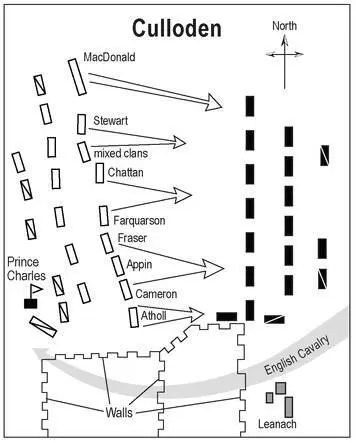

On April 16, 1746, about six miles from Inverness, on the Drumossie moor, Bonnie Prince Charlie and his ragtag army of Highlanders faced the duke of Cumberland in what would be the decisive battle in the Jacobite cause. Charlie fought on behalf of his father, the Old Pretender, James Francis Edward Stuart, in a bid to seize power from George II. He was expected to lead the Jacobites into glory, thereby laying the ground for what might have been the rebirth of the Scottish nation under Stuart rule. Instead, he led his men to slaughter and forever buried any dreams of a ruling Stuart dynasty.

The Jacobite cause had its beginnings in the Tudor dynasty. When Elizabeth I of England failed to produce an heir, the Scottish king James VI came to rule as king of both England and Scotland. The Stuart dynasty, which traced its lineage back to the daughter of Robert the Bruce, became the supreme ruling power over a united English-Scottish empire. After the Cromwellian takeover and the beheading of Charles I, a new enemy of the people arose—the Catholics, who were viewed with great suspicion. The Anti-Catholic Test Acts, put into commission at the time of Charles II, required that all holders of public office be Protestant.

This posed certain problems for James II, brother and heir to Charles II. James lived in exile in France during the English Civil War and even served in the French army. If being raised as a Frenchman weren’t bad enough, he was also a Catholic. Although his two daughters, Mary and Anne, grew up as Protestants, it was not enough to secure his popularity with the people. He did not have the charm and charisma that his brother had. He also seemed to lack a sense of humor and was even nicknamed “Dismal Jimmie” by the Scots. Suspicions grew when James issued the Declaration of Indulgence establishing freedom of worship for all Catholics.

Opponents of James invited his daughter Mary and her Dutch husband, William of Orange, to take over as joint rulers of England and Scotland. When William landed and advanced toward London, James fled the country. William and Mary took their oaths of coronation on April 21, 1689. Despite the newly established monarchy, James still had a small group of supporters, mostly in the Scottish Highlands. They were known as the Jacobites (from Jacobus , the Latin version of his name). His only real chance at regaining power came in 1690 in Boyne, Ireland. But James lost his nerve, turned tail, and ran. His lack of courage earned him the Irish nickname Seamus an Chaca , or James the Shite.

The defeat did not silence the Jacobite movement. For the next fifty years, there were plots, skirmishes, revolts, uprisings, and massacres all in the name of Dismal Jimmie. But in 1746 a new champion for the cause swept his way across the British Isles. Though James II had long been deceased, his grandson Charles Edward Stuart decided to take up the challenge. By this time, most of Scotland was apathetic toward the Jacobites. Support for them came mostly from the Highlanders, who were looked on by the city dwellers as being mostly bandits. The rest of the Scottish populace favored the Hanoverian king, George II. And, it should be noted that George was the great-great-grandson of James I, thereby making him a direct descendant of the Stuart line, a fact polished over by many historians. The main objection to him seemed to be more about the fact that he was German and less about his lineage. So, the Italian-born, French-speaking darling of the Highlanders sought to depose him.

The Bonnie prince teamed up with Lord George Murray, who became his field commander. Together, the two took Edinburgh and then trounced Hanoverian forces at Prestonpans. They pressed on to England, where the people feared the worst. There was a run on the bank in London and general panic ensued. The panic proved to be premature. When Charlie realized he had no support in England, he turned his forces around just 100 miles outside of London and headed back to Scotland. He decided to go head-to-head with the king’s son, William Augustus, the duke of Cumberland. So far, Charlie had been considerably lucky. He controlled much of Scotland and had his followers convinced he could easily take the rest. But facing a force of 9,000 trained British soldiers with 5,000 untrained Highlanders was folly. Going against the advice of Lord Murray, the prince continued onward and concentrated his forces on the Drumossie moor near Culloden house. He lay in wait for the British army to arrive.

It seems the duke had better things to do than fight a battle with the rebellious Scots. He stopped eight miles away in Nairn to celebrate his twenty-fifth birthday. When Charlie heard this, he decided to surprise the duke. He gathered his troops and attempted to march over the moors at night. The march proved too challenging for the tired, starving Highlanders, so they turned around and went back to their original position. They had exhausted themselves on the long trek through the moors and were ill-prepared for the battle yet to come. The following morning, the duke met up with the Jacobite forces.

His actions were well calculated and well implemented. He began with a barrage of artillery aimed directly at the Highland infantry. To parry the onslaught, the infantry ran full-on toward the enemy. The British infantry made ready. They stood fast in three ranks, one kneeling, the next stooping, and the third standing. Cumberland had another trick up his sleeve. He had trained his men to attack to their left in order to evade the Highlanders’ target, while thrusting under the sword arm. His plan was effective. Hanoverian forces rendered the Highlanders’ assault on the left flank useless and managed to outflank them on the right. The Jacobites began a hasty retreat. In the end, 1,000 Highlanders lost their lives and 1,000 more were taken prisoner.

The Battle of Culloden

Charlie became a fugitive with a £30,000 price on his head. He eventually made his way back to France and died a rather anticlimactic death four decades later, after many years of drowning his sorrows in the bottle and reminiscing on what might have been. Had he been more patient, the Bonnie prince might have become the reigning king of an independent Scottish nation. He needed only to concentrate his efforts in the north instead of trying to gather support in the staunchly Hanoverian English counties. Because of his poor judgment and lack of skills as a military leader, Charles ensured that the Jacobite cause would be lost in the annals of history forever.

Читать дальше