5. The O-ring erosion history presented to Level I at NASA Headquarters in August 1985 was sufficiently detailed to require corrective action prior to the next flight.

6. A careful analysis of the flight history of O-ring performance would have revealed the correlation of O-ring damage and low temperature. Neither NASA nor Thiokol carried out such an analysis; consequently, they were unprepared to properly evaluate the risks of launching the 51-L mission in conditions more extreme than they had encountered before.

The Commission found that safety standards at NASA had declined since the Apollo program:

1. Reductions in the safety, reliability and quality assurance work force at Marshall and NASA Headquarters have seriously limited capability in those vital functions.

2. Organizational structures at Kennedy and Marshall have placed safety, reliability and quality assurance offices under the supervision of the very organizations and activities whose efforts they are to check.

3. Problem reporting requirements are not concise and fail to get critical information to the proper levels of management.

4. Little or no trend analysis was performed on O-ring erosion and blow-by problems.

5. As the flight rate increased, the Marshall safety, reliability and quality assurance work force was decreasing, which adversely affected mission safety.

6. Five weeks after the 51-L accident, the criticality of the Solid Rocket Motor field joint was still not properly documented in the problem-reporting system at Marshall.

The Commission found that the system had come under additional pressure:

With the 1982 completion of the orbital flight test series, NASA began a planned acceleration of the Space Shuttle launch schedule. One early plan contemplated an eventual rate of a mission a week, but realism forced several downward revisions. In 1985, NASA published a projection calling for an annual rate of 24 flights by 1990. Long before the Challenger accident, however, it was becoming obvious that even the modified goal of two flights a month was overambitious.

In establishing the schedule, NASA had not provided adequate resources for its attainment. As a result, the capabilities of the system were strained by the modest nine-mission rate of 1985, and the evidence suggests that NASA would not have been able to accomplish the 14 flights scheduled for 1986. These are the major conclusions of a Commission examination of the pressures and problems attendant upon the accelerated launch schedule.

In detail the Commission found that:

1. The capabilities of the system were stretched to the limit to support the flight rate in winter 1985/1986. Projections into the spring and summer of 1986 showed a clear trend: the system, as it existed, would have been unable to deliver crew training software for scheduled flights by the designated dates. The result would have been an unacceptable compression of the time available for the crews to accomplish their required training.

2. Spare parts are in critically short supply. The Shuttle program made a conscious decision to postpone spare parts procurements in favor of budget items of perceived higher priority. Lack of spare parts would likely have limited flight operations in 1986.

3. Stated manifesting policies are not enforced. Numerous late manifest changes (after the cargo integration review) have been made to both major payloads and minor payloads throughout the Shuttle program.

Late changes to major payloads or program requirements can require extensive resources (money, manpower, facilities) to implement.

If many late changes to “minor” payloads occur, resources are quickly absorbed.

Payload specialists frequently were added to a flight well after announced deadlines.

Late changes to a mission adversely affect the training and development of procedures for subsequent missions.

4. The scheduled flight rate did not accurately reflect the capabilities and resources.

The flight rate was not reduced to accommodate periods of adjustment in the capacity of the work force. There was no margin in the system to accommodate unforeseen hardware problems.

Resources were primarily directed toward supporting the flights and thus not enough were available to improve and expand facilities needed to support a higher flight rate.

5. Training simulators may be the limiting factor on the flight rate: the two current simulators cannot train crews for more than 12–15 flights per year.

6. When flights come in rapid succession, current requirements do not ensure that critical anomalies occurring during one flight are identified and addressed appropriately before the next flight.

The Commission noted that engine testing had been reduced:

The Space Shuttle Main Engine teams at Marshall and Rocketdyne have developed engines that have achieved their performance goals and have performed extremely well. Nevertheless the main engines continue to be highly complex and critical components of the Shuttle that involve an element of risk principally because important components of the engines degrade more rapidly with flight use than anticipated. Both NASA and Rocketdyne have taken steps to contain that risk. An important aspect of the main engine program has been the extensive “hot fire” ground tests. Unfortunately, the vitality of the test program has been reduced because of budgetary constraints.

The number of engine test firings per month has decreased over the past two years. Yet this test program has not yet demonstrated the limits of engine operation parameters or included tests over the full operating envelope to show full engine capability. In addition, tests have not yet been deliberately conducted to the point of failure to determine actual engine operating margins.

The members of the Commission included former astronauts, Neil Armstrong and Sally Ride, and the former test pilot, General Charles Yeager, as well as scientists and lawyers.

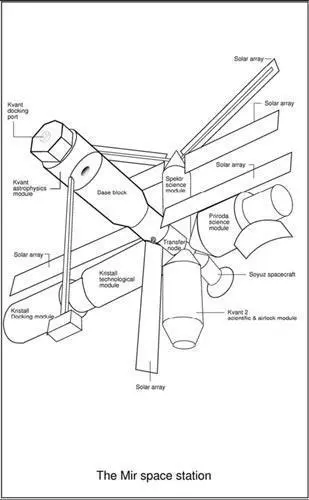

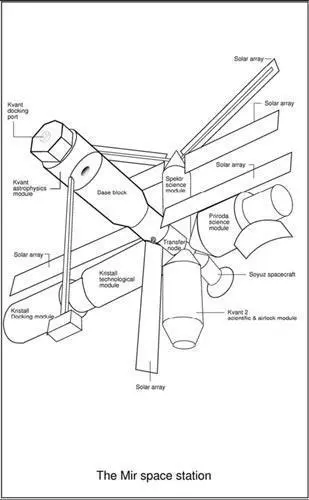

The last and biggest of the Soviet space stations was Mir (Mir means “Peace”).

Mir was launched by Proton booster on 20 February 1986. The first module was the base unit which contained the command centre and the living quarters. The Kvant astrophysics laboratory was added in 1987, while another module, Kvant 2, was added in November 1989; Kvant 2 included a new toilet and shower. The Kristall module followed six months later.

On 21 December 1987 the Soviet cosmonauts, Colonel Vladimir Titov and Muso Manarov, began a record endurance flight of 366 days aboard Mir and their Soyuz TM-4. At that time the space station only consisted of the base unit and the Kvant astrophysics module. The two cosmonauts returned on 21 December 1988.

When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991 Russia inherited most of the Soviet Space program, parts of which were located in other states of the former Soviet Union – for example, the automatic docking system was made in the Ukraine. Having to buy or lease facilities and equipment added to the financial difficulties of supporting their space program.

They had to cancel many projects, including their own version of the space shuttle, the “Buran” and their fleet of communications vessels was laid up. Consequently they could not maintain continuous communications with their space stations.

In June 1992 US President George Bush and Russian President Boris Yeltsin agreed to a pioneering space-co-operation agreement. One American astronaut would fly aboard the Mir space station; two Russian cosmonauts would fly aboard the US space shuttle.

Читать дальше