On the return journey the Apollo 12 astronauts were witness to the first eclipse of the Sun by the Earth. The three astronauts watched a thin sliver of Sun behind the dark mass of the moonlit Earth, and took the first photographs of the Earth’s atmosphere backed by the Sun. The dark side of the Earth was laced with lightning flashes along the equator and the specular light of the full Moon behind them gleamed off the black oceans. Alan Bean decided it was the most spectacular view of the whole flight.

At 2:58 pm Houston time Apollo 12 landed in a rough Pacific Ocean on 24 November, 7.2 kilometres from the carrier USS Hornet . Bean was standing by to quickly punch two circuit breakers to cast off the parachutes before they were pulled over upside down. The Command Module hit the sea with such a jolt Bean felt momentarily dizzy, although he heard Gordon call out, “Hey Al, hit the breakers,” as they began to turn over.

Gordon queried, “Al, what happened?”

“Nothing happened, what are you talking about?”

“You’re bleeding?” Conrad was looking at a gash above Bean’s eye where the 16mm movie camera had broken loose and struck Bean.

A surprised Bean told his companions, “It must have knocked me out for a few seconds, and I didn’t even know it?”

After a welcome on the Hornet , Bean required two stitches in the sick bay before the astronauts were taken to the Lunar Receiving Laboratory for their eleven days, and the second mission to the Moon’s surface was safely over. Apollo 12 had proved the navigation systems were accurate enough to land on the chosen spot, the hardware systems, including the ALSEP, were good enough to support the requirements of the mission, and the astronauts were able to do useful work in a lunar environment.

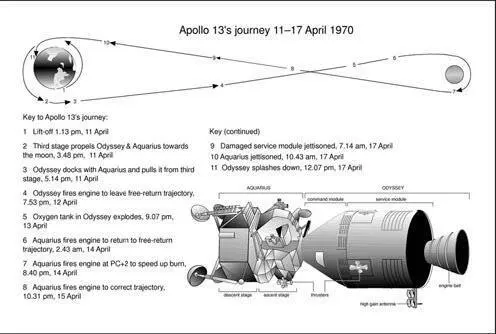

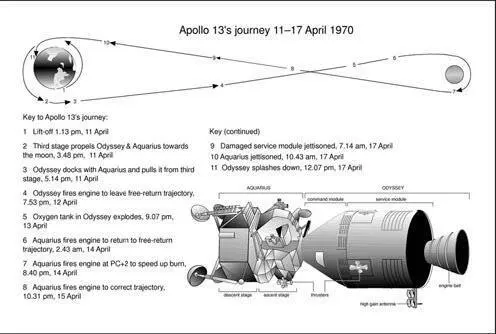

Apollo 13’s problem – 11–17 April 1970

Apollo 13’s mission was to make the third landing on the moon.

Sy Liebergot was the flight controller in charge of EECOM (Electrical & Environmental Command console) which monitored the power and life support systems. He had worked on the missions of Apollo 11 & 12.

Jim Lovell, Ken Mattingly and Fred Haise were the designated crew of Apollo 13, which would be out of communication for 40 minutes of every lunar orbit. A lunar orbit took 2 hours.

Liebergot had failed to react to loss of cabin pressure during a simulation exercise. Gene Kranz was the flight director of Liebergot’s team (Kraft had become part of the management team) and made his controllers do a simulated rescue plan which involved using the LEM as a lifeboat while still attached to the command module.

The back-up crew of Apollo 13 were John Young, Jack Swigert and Charlie Duke. Duke caught German measles from his children. Lovell and Haise were immune because they had already had it, but Mattingly had not had it so he was replaced by Swigert.

In his biographical account Jim Lovell referred to himself in the third person, as Lovell. He described the Apollo command module:

The Apollo command module was an eleven-foot-tall cone shaped structure, nearly thirteen feet wide at the base. The walls of the crew compartment were made of a thin sandwich of aluminium sheet and an insulating honeycomb filler. Surrounding that was an outer shell of a layer of steel, more honeycomb, and another layer of steel. These double bulkheads – no more than a few inches thick – were all that separated the astronauts inside the cockpit from the near-absolute vacuum of an outside environment where temperatures ranged from a gristle-frying 280 degrees Fahrenheit in sunlight to a paralyzing minus 80 degrees in shadow. Inside the ship, it was a balmy 72.

The astronauts’ couches lay three abreast, and were actually not couches at all. Since the crew would spend the entire flight in a state of weightless float, they had no padding beneath them to support their bodies comfortably; instead, each so-called couch was made of nothing more than a metal frame and a cloth sling – easy to build and most important, light. Each couch was mounted on collapsible aluminum struts, designed to absorb shock during splashdown if the capsule parachuted into the sea – or in the case of a mistargeted touchdown, onto land – without too much of a jolt. At the foot of the three cots was a storage area that served as a sort of second room (Unheard of! Unimaginable in the Gemini and Mercury eras!) called the lower equipment bay. It was here that supplies and hardware were stored and the navigation station was located.

Directly in front of the astronauts was a big, battleship-gray 180 degree instrument panel. The five hundred or so controls were designed to be operated by hands made fat and clumsy by pressurized gloves, and consisted principally of toggle switches, thumb wheels, push buttons, and rotary switches with click stops. Critical switches, such as engine firing and module-jettisoning controls, were protected by locks or guards, so that they could not be thrown accidentally by an errant knee or elbow. The instrument panel readouts were made up primarily of meters, lights, and tiny rectangular windows containing either “gray flags” or “barber poles.” A gray flag was a patch of gray metal that filled the window when a switch was in its ordinary position. A striped flag like a barber pole would take its place when, for whatever reason, that setting had to be changed.

At the astronauts’ backs, behind the heat shield that protected the bottom of the conical command module during re-entry, was the twenty-five-foot, cylindrical service module. Protruding from the back of the service module was the exhaust bell for the ship’s engine. The service module was inaccessible to the astronauts, in much the same way the trailer of a truck is inaccessible to the driver in the cab. (Since the windows of the command module faced forward, the service module was invisible to the astronauts as well). The interior of the service module cylinder was divided into six separate bays, which contained the entrails of the ship – the fuel cells, hydrogen power relay stations, life-support equipment, engine fuel and the guts of the engine itself. It also contained – side by side, on a shelf in bay number four – two oxygen tanks.

At the other end of the command module-service module stack, connected to the top of the command module by an airtight tunnel, was the LEM. The four-legged twenty-three-foot tall craft had an altogether awkward shape that made it look like nothing so much as a gigantic spider. Indeed, during Apollo 9, the lunar module’s maiden flight, the ship was nicknamed “Spider,” and the command module was called by an equally descriptive “Gumdrop.” For Apollo 13, Lovell had opted for names with a little more dignity, selecting “Odyssey” for his command module and “Aquarius” for his LEM. The press had erroneously reported that Aquarius was chosen as a tribute to Hair – a musical Lovell had not seen and had no intention of seeing. The truth was, he took the name from the Aquarius of Egyptian mythology, the water carrier who brought fertility and knowledge to the Nile valley. Odyssey he chose because he just plain liked the ring of the word, and because the dictionary defined it as “a long voyage marked by many changes of fortune” – though he preferred to leave off the last part. While the crew compartment of Odyssey was a comparatively spacious affair, the lunar module’s crew compartment was an oppressively cramped, seven-foot eight-inch sideways cylinder that featured not the five portholes and panoramic dashboard of the command module but just two triangular windows and a pair of tiny instrument panels. The LEM was designed to support two men, and only two men, for up to two days. And only two days.

Читать дальше