I wondered why the men in the chopper did not try coming in for me. I was panting hard, and every time a wave lapped over me I took a big swallow of water. I tried to rouse them by waving my arms. But they just seemed to wave back at me. I wasn’t scared now. I was angry. Then I looked to my right and saw a third helicopter coming my way and dragging a horse collar behind it across the water. In the doorway I spotted Lieutenant George Cox, the Marine pilot who had handled the recovery hook which picked up both Al Shepard and the chimp, Ham. As soon as I saw Cox, I thought, “I’ve got it made.”

The wash from the other helicopters made it tough for Cox to move in close. I was scared again for a moment, but then, somehow, in all that confusion, Cox came in and I got hold of the sling. I hung on while they winched me up, and finally crawled into the chopper. Cox told me later that they dragged me fifteen feet along the water before I started going up. I was so exhausted I cannot remember that part of it. As soon as I got into the chopper I grabbed a Mae West and started to put it on. I wanted to make certain that if anything happened to this helícopter on the way to the carrier I would not have to go through another dunking!

When I had been aboard the carrier for some time an officer came up and presented me with my helmet. I had left it behind in the sinking capsule, but somehow it had bobbed loose and a destroyer crew had picked it up as it floated in the water.

“For your information,” the officer said, “we found it floating right next to a ten-foot shark.”

This was interesting, but it was small consolation to me. We had worked so hard and had overcome so much to get Liberty Bell launched that it just seemed tragic that another glitch had robbed us of the capsule and its instruments at the very last minute. It was especially hard for me, as a professional pilot. In all my years of flying this was the first time that my aircraft and I had not come back together. Liberty Bell was the first thing I had ever lost.

We tried for weeks afterwards to find out what had happened and how it had happened. I even crawled into capsules and tried to duplicate all of my movements, to see if I could make the same thing happen again. But it was impossible. The plunger that detonates the bolts is so far out of the way that I would have had to reach for it on purpose to hit it, and this I did not do. Even when I thrashed about with my elbows, I could not manage to bump against it accidentally. It remains a mystery how that hatch blew. And I am afraid it always will. It was just one of those things.

Fortunately, the telemetry system worked well during the flight, and we got back enough data while I was in the air to answer the questions that I had gone out to ask. We missed the capsule, of course. It had film and tapes aboard which we would have liked to study. But despite all our headaches along the way, and an unhappy ending, Liberty Bell had performed her mission. She had flown me 302.8 miles downrange, had taken me to an altitude of 118.2 miles at a speed of 5,168 mph, had put me through five minutes of weightless flight, and had brought me home, safe and sound. That was all that really mattered. The system itself was valid. The problems which had plagued us could be fixed, and with our second and final sub-orbital mission under our belts, we were ready now for the big one – three orbits of the world.

More sub-orbital flights were scheduled but on 6 August 1961 the Russian cosmonaut Major Yuri Titov made a 17-orbit flight which lasted 25 hours. NASA was hoping to put a man into orbit before the end of the year and this time it would be Glenn. He decribed the preparations:

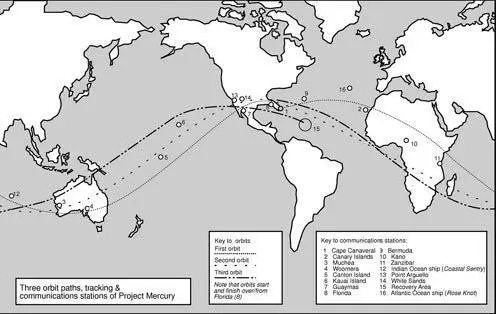

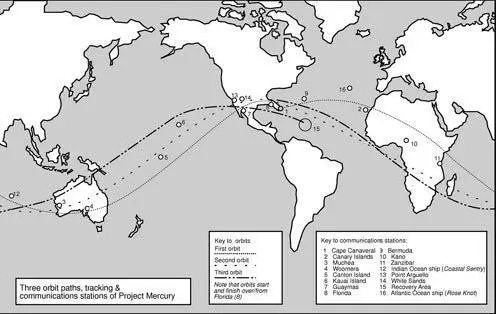

Atlas testing moved into its final phase. A September 13 Atlas launch, MA-4, carried a dummy astronaut into orbit and back after circling Earth once, and the capsule landed on target in the Atlantic. At that point the system seemed ready. The Atlas had been strengthened not only by the belly band but with the use of thicker metal near the top. But Bob Gilruth and Hugh Dryden, NASA’s deputy administrator, wanted to send a chimp into orbit before risking a man.

This time the chimp was named Enos, and he went up on November 29. Like Ham, he had been conditioned to pull certain levers in the spacecraft according to signals flashing in front of him. Like Ham’s, his flight was not altogether perfect. The capsule’s attitude control let it roll 45 degrees before the hydrogen peroxide thrusters corrected it. Controllers brought it down in the Pacific after two orbits and about three hours.

When Enos was picked up he had freed an arm from its restraint, gotten inside his chest harness, and pulled off the biosensors that the doctors had attached to record his respiration, heartbeat, pulse, and blood pressure. He also had ripped out the inflated urinary catheter they had implanted, which sent his heart rate soaring during the flight. It made you cringe to think of it.

Nevertheless, Enos’s flight was a success and he appeared unfazed at the postflight news conference with Bob and Walt Williams, Project Mercury’s director of operations. All the attention was on the chimpanzee when one of the reporters asked who would follow him into orbit.

Bob gave the world the news I’d learned just a few weeks earlier, when he had called us all into his office at Langley to tell us who would make the next flight. I had been elated when, at last, I heard that I would be the primary pilot. This time I was on the receiving end of congratulations from a group of disappointed fellow astronauts. Now, as the reporters waited with their pencils poised and cameras running, Bob said, “John Glenn will make the next flight. Scott Carpenter will be his backup.”

The launch date was originally set for 16 January but due to bad weather it was postponed until 23 January. Glenn:

I woke up at about one-thirty on the morning of February 20, 1962. It was the eleventh date that had been scheduled for the flight. I lay there and went through flight procedures, and tried not to think about an eleventh postponement. Bill Douglas came in a little after two and leaned on my bunk and talked. He said the weather was fifty-fifty and that Scott had already been up to check out the capsule and called to say it was ready to go. I showered, shaved, and wore a bathrobe while I ate the now-familiar low-residue breakfast with Bill, Walt Williams, NASA’s preflight operations director, Merritt Preston, and Deke Slayton who was scheduled to make the next flight.

Bill gave me a once-over with a stethoscope and shone a light into my eyes, ears, and throat. “You’re fit to go,” he said and started to attach the biosensors. Joe Schmitt laid out the pressure suit’s various components, the suit itself, the helmet, and the gloves, which contained fingertip flashlights for reading the instruments when I orbited from day into night. I put on the urine collection device that was a version of the one Gus and I had devised the night before his flight, then the heavy mesh underliner with its two layers separated by wire coils that allowed air to circulate. I put the silver suit on – one leg at a time, like everybody else, I reminded myself. In a pocket in addition to the small pins I had designed, I carried five small silk American flags. I planned to present them to the President, the commandant of the Marine Corps, the Smithsonian Institution, and Dave and Lyn.

Joe gave the suit a pressure check, and Bill ran a hose into his fish tank to check the purity of the air supply; dead fish would mean bad air. I was putting on the silver boots and the dust covers that would come off once I was through the dust-free “white room” outside the capsule at the top of the gantry when I said casually, “Bill, did you know a couple of those fish are floating belly-up?”

Читать дальше