—François Furet, “Sur l’illusion communiste”

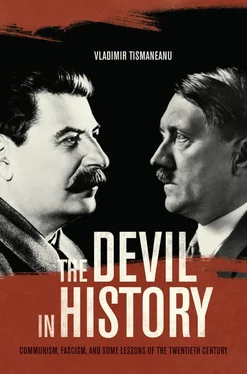

Understanding the meanings of the twentieth century is impossible if we do not acknowledge the uniqueness of the revolutionary left and right experiments in reshaping the human condition in the name of presumably inexorable historical laws. It was during that century that, using Leszek Kołakowski’s inspired term, “the Devil incarnated himself in History.” The ongoing debate on the nature and the legitimacy (or even acceptability) of comparisons (analogies) between the ideologically driven revolutionary tyrannies of the twentieth century (radical Communism, or rather, Leninism, or, as some prefer, Stalinism) on one hand and radical Fascism (or, more precisely, Nazism) on the other bear on the interpretation of ultimate political evil and its impact on the human condition. 1In brief, can one compare two ideologies (and practices) inspired by essentially different visions of human nature, progress, and democracy, without losing their differentia specifica , blurring important doctrinary but also axiological distinctions? Was the essential centrality of the concentration camp, the only “perfect society,” as Adam Michnik once put it, the horrifying common denominator between the two systems in their “highly effective” stage? (Zygmunt Bauman writes about our age as a “century of camps.” 2) Was François Furet right in assuming that Communism’s heredity was to be detected in the post-Enlightenment search for mass democracy, whereas Fascism symbolized the very opposite? 3Was Fascism, as Eugen Weber asserted, “a rival revolution” that saw Communism only as a “competitor for the foundation for power” (in the words of Jules Monnerot)? 4

Comparisons between Communism and Fascism and between Stalinism and Nazism are both useful and necessary. My comparative endeavor focuses on the common ground of these political movements, while also recognizing their crucial differences. 5Moreover, I agree with Timothy Snyder that “the Nazi and Stalinist systems must be compared, not so much to understand the one or the other but to understand our times and ourselves.” 6Communism and Fascism forged their own versions of modernity based on programs of radical change that advocated homogenization as well as social, economic, and cultural transformation presupposing “the wholesale renovation of the body of the people.” 7They were both founded upon immanent utopias rooted in eschatological fervor. To put it differently, the ideological storms of the twentieth century were the expression of a contagious hubris of modernity. Therefore, the lessons we learn by comparing and contrasting them have a universal, almost timeless meaning for any society that wants to avoid a disastrous descent into barbarity and genocidal forms of extermination. Contemporary dilemmas of a globalized world can only benefit from examination of the disastrous fallacies of the past.

Here it is important to highlight the point made by Claude Lefort and Richard Pipes: Leninism was a mutation in the praxis of social democracy, not just a continuation of the “illuminist”—democratic legacies of socialism. Equally significant, precisely because he insisted so much on the “causal nexus” and counterrevolutionary anguish and fears, German historian Ernst Nolte did not fully grasp the nature of Fascist anti-Bolshevism as a new type of revolutionary movement and ideology, a rebellion against the very foundations of European modern civilization. Indeed, as Furet (and, earlier, Eugen Weber and George Lichtheim) insisted, Fascism, in its radicalized, Nazi form, was not simply a reincarnation of counterrevolutionary thinking and action. 8Nazism was more than just a reaction to Bolshevism, or to the cult of progress and the sentimental exaltation of abstract humanity symbolized by the proletariat. It was in fact something brand new, an attempt to renovate the world by getting rid of the bourgeoisie, the gold, the money, the parliaments, the parties, and all the other “decadent,” “Judeo-plutocratic” elements. So Fascism was not a counterrevolution, as the Comintern ideologues maintained; rather it is itself a revolution. Or, to use Roger Griffin’s more figurative phrasing, “The arrow of time points not backwards but forwards, even when the archer looks over his shoulder for guidance where to aim.” According to the same author, Fascism was “a revolutionary form of nationalism…. [T]he core myth that inspires this project is that only a populist, trans-class movement of purifying, cathartic national rebirth (palingenesis) can stem the tide of decadence.” 9At stake is the reaction to the “system,” that is, to bourgeois-individualistic values, rights, and institutions. When Lenin disbanded the Constituent Assembly in January 1918, he was sanctioning a long-held scorn for representative democracy and popular sovereignty. The one-party system, emulated by Mussolini and Hitler, was thus invented as a new form of sovereignty that was contemptuous of individuals, fragmentation, deliberation, and dialogue. On January 6, 1918, celebrating the dissolution of pluralism, Pravda published the following:

The hirelings of bankers, capitalists, and landlords, the allies of Kaledin, Dutov, the slaves of the American dollar, the backstabbers, the right-essers demand in the Constitutional Assembly all power for themselves and their masters—enemies of the people. They pay lip service to popular demands for land, peace, and [worker] control, but in reality they tried to fasten a noose around the neck of socialist authority and revolution. But the workers, peasants, and soldiers will not fall for the bait of lies of the most evil of socialism. In the name of the socialist revolution and the socialist soviet republic they will sweep away its open and hidden killers. 10

One of the most acerbic reactions to the decision by Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev, Nikolai Yakov Sverdlov, and their companions to disband the remains of democracy in Russia came from the jailed Polish-German Marxist thinker Rosa Luxemburg in her manuscript notes on the Russian Revolution. In his trilogy, Leszek Kołakowski quotes Luxemburg’s comment: “Freedom only for supports of the government, only for members of the single party, however numerous—this is not freedom. Freedom must always be for those who think differently.” Kołakowski accurately captured the thrust of Rosa Luxemburg’s criticism of Bolshevism:

Socialism was a live historical movement and could not be replaced by administrative decrees. If public affairs were not properly discussed they would become the province of a narrow circle of officials, and corruption would be inevitable. Socialism called for a spiritual transformation of the masses, and terrorism was no way to bring this about: there must be unlimited democracy, a free public opinion, freedom of elections and the press, the right to hold meetings and form associations. Otherwise the only active part of society would be bureaucracy: a small group of leaders who give orders, and the workers’ task would be applaud them. The dictatorship of the proletariat would be replaced by the dictatorship of a clique. 11

The European civil war did indeed take place in the twentieth century, but its main stake was not the victory of Bolshevism over Nazism (or vice versa). It was rather their joint offensives against liberal modernity. 12Both totalitarian movements were intoxicated with “a state of expectancy induced by the intuitive certainty that an entire phase of history is giving way to a new one”—a mood of Aufbruch that became the ideological rationale for the totalist project to engineer reality. 13This explains the readiness of so many Communists to acquiesce in Soviet-Nazi complicity, including the 1939 “nonaggression” pact: the radical militants saw the “decadent” Western democracies as doomed to disappear, and they were therefore willing to ally themselves with the equally antibourgeois Fascists. This is not to say that anti-Fascism was just a propaganda device for the Comintern, or that anti-Marxism was not a central component of National Socialism. The point is that the two movements were essentially and unflinchingly opposed to democratic values, institutions, and practices. German political thinker Karl Dietrich Bracher once memorably stated that “totalitarian movements are the children of the age of democracy.” 14In their most accomplished form, in the Soviet Union and Germany, Leninism and Fascism represented “a ferocious attack on and a frightening alternative to liberal modernity.” 15Their simultaneous experiences situated them in “a ‘negative intimacy’ in the European framework of ‘war and revolution’” 16—a “mortal embrace” 17that increased suffering and destruction to a level unprecedented in history.

Читать дальше