I would like to return now to Ralf Dahrendorf’s memorable statement that citizens of Central and Eastern Europe are still trying to make sense of their existence. As mentioned earlier, a constant of the recent history of the region is the recurrence of charismatic politics and of pseudo-party politics. If these societies are to move past these problems, they must overcome two fundamental elements of the legacy of the Communist past: anomy (which led to fragmentation, neotraditionalism, and uncivility, to what Romanian philosopher Andrei Pleșu termed “public obscenity”) and lies (which led to dissimulation and the disintegration of consensus, and ostentatiously brought forth a human type characterized by Russia sociologist Yuri Levada as homo prevaricatus , the heir of homo sovieticus). Since forewarned is forearmed, I believe that it is better to look into the real pitfalls and avoid them rather than play the obsolete pseudo-Hegelian tune of the “ultimate liberal triumph.” Indeed, what we see here is not the strength but rather the vulnerability of liberalism in the region—the backwardness, delays, and distortions of modernity, as well as its periodic confrontation with majoritarian, neoplebiscitarian parties and movements. 92The lesson of the 1989 revolutions is therefore multifarious. It refers to the rebirth of citizenship, a category abolished by both Communism and Fascism, 93but it also involved re-empowering the truth. What we have learned from 1989 represents an unquestionable argument in favor of the values that we consider essential and exemplary for democracy today.

Let us end by noting the vital role played by international factors in the process of the democratization of Eastern and Central Europe. Without NATO’s enlargement and accession to European Union, the fate of the region most probably would have been very different. Because of normalization by integration into a democratically validated supragovernmental organization, the political, cultural, economic, and social environments in these countries have received a huge boost in their struggle with mytho-exclusionist fantasies. In this sense, external intervention was as important, if not more important, than domestic dynamics. What seemed in the early 1990s a somber future turned into an extremely favorable present. Ken Jowitt rightly diagnosed that only adoption by a richer sister from the West could save the tormented Eastern sister from a new wave of salvationist authoritarianism. And indeed his doomsday vision of colonels, priests, and despots was proven wrong. This was a surprise, though, for none of us thought that NATO and the European Union would turn eastward. There were calls for this, but they seemed more like hoping against hope. It is no surprise, then, that Jowitt emphatically stated in 2007 that integration in the EU was the best news that the countries of Central and Eastern Europe had received in five hundred years. One should not forget, however, the part played by the shock of Yugoslavia’s secession wars. This tragic and violent example made both the EU and NATO understand where ignorance of the dangers of nationalism, populism, and demagogy in the region can lead. Their push eastward had as great a civilizing role as the exercise of democracy within these societies. The specter that one should be wary of now is, to invoke Jowitt once again, the transformation of the former members of the Warsaw Pact into the ghetto of a united Europe. 94

Any assessment of the last two decades should raise the question, What is it left of 1989? This turning point was the most powerful shake-up in the twentieth century of the seduction exerted by millenarian ideologies. The teleological utopias of the last century were fundamentally rebuked by the revolutions of 1989, which were their polar opposite. They were anti-ideological, antiteleological, and anti-utopian. They rejected the exclusive logic of Jacobinism and refused to embark on any new chiliastic experiments. In this sense, they can be called non-revolutionary. Indeed, the Leninist extinction could be explained, following Stephen Kotkin for instance, by appealing to “a narrative of global political economy and a bankrupt political class in a system that was largely bereft of corrective mechanisms.” 95But this would ultimately overlook (or significantly diminish) the equally relevant tale of a slow but unstoppable awakening of society by reinstating the centrality of truth and human rights (especially after the 1975 Helsinki Agreement). The uncivil society was not merely confronted with the erosion of its Leninist worldview. It also imploded in the face of an alternative set of values that inspired independent reflection, autonomous initiatives, and mass protest. In other words, the upheaval of 1989 was not only the result of the agency of the uncivil society. It acted in the presence of a powerful political myth—civil society. political myths are to be judged not in terms of their truthfulness, but of their potential to become true: speaking about civil society led to the emergence of civil society. In East Central Europe, exhilarating new ideas, such as the return to Europe, destroyed obsolete ideas. People took to the streets in Berlin, Leipzig, Prague, Budapest, and Timisoara, convinced that the hour of the citizen had arrived.

In 1989, public demonstrations did not lead directly to the collapse of the Communist elites in power. Maybe civil society was not the immediate cause of the demise of Erich Honecker, Wojciech Jaruzelski, Todor Zhivkov, Miloš Jakeš, and Gustáv Husák. But the dynamics, the ideas, and most important, the aftermath of the events accompanying the shattering of Communist parties’ rule across the region cannot be understood without emphasizing the significance of civil society as a constellation of fundamental ideas, as a political myth, and as a real, historical movement that accompanied the implosion of Eastern European party-states. To take my point even further, the very idea of revolutions in 1989 rests on the impact of civil society, which replaced the existing political, social, and economic system with one founded on the ideals of democratic citizenship and human rights. Yes, there were many masks, travesties, charades, and myths involved in the events that took place in Bucharest, Prague, and Sofia. In most countries, the resilience of the old elites prevented a radical coming to terms with the Communist past. But this obfuscates the fact that the core value restored, cherished and promoted by the revolutions of 1989 was common sense. The revolutionaries believed in civility, decency, and humanity, and they succeeded in rehabilitating these values. This is the most significant lesson of 1989. The illusions of that year ought not to be discarded: they were crucial for the defeat of Leninism. In 1989, people were not afraid anymore; their moral frustration, social numbness, and political impotence disappeared. The individual finally regained a central role on the political stage. The years passed and ultimately those nightmarish scenarios for Central and Eastern Europe have been invalidated. Far from being over, the revolutions of 1989 remain a symbol of contemporary times—an age of diversity, difference, and tolerance.

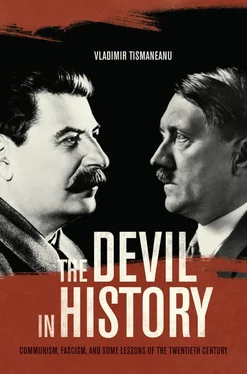

Totalitarianism was a novel political, social, and cultural construct that first suspended and then abolished traditional distinctions between good and evil. An imperfect concept, to be sure, it was not an empty signifier or a mere Cold War propaganda weapon, as some have suggested in recent years. Those who developed the concept of totalitarianism during the interwar period knew what appalling realities it designated: from the exiled Mensheviks to the emigré scholars from Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, these intellectuals knew that something unprecedented and quite terrifying had occurred. 1The concept of totalitarianism offered important and still valid interpretive keys for understanding the unique blending of ideology, organization, and terror in unprecedented attempts to create perfectly homogenized communities through genocidal methods. All these experiments included quasi-religious, unavowed yet palpable mystical components. In fact, they were political religions, with their own rituals, prophets, saints, zealots, inquisitors, traitors, renegades, heretics, apostates, and holy writs. The totalitarian story began with the Bolshevik dream of total revolution and became a global phenomenon in the 1920s and 1930s with the rise to power of totalitarian party-movements in Italy and Germany. For example, the Romanian Iron Guard was a totalitarian movement that combined political radicalism and religious fanaticism. Its short-lived stay in power (September 1940-January 1941) was marked by a frantic attempt to carry out, using murderous violence, what historian Eugen Weber once called the archangelic revolution. 2Whereas these Fascist dictatorships collapsed as a result of World War II, Soviet Communism lasted for more than seven decades and ended only in December 1991 in the USSR. The catalyst for this final wreckage was the liberal, anti-Leninist revolutionary upheaval of 1989. In transformed incarnations, it is still alive in China and a few other countries.

Читать дальше