To return to the Black Book , I wish to emphasize that the key point concerning its legacy is the legitimacy of the comparison between National Socialism and Leninism. I agree here with the Polish-French historian Krzysztof Pomian’s approach:

It is undeniable that mass crimes did take place, as well as crimes against humanity, and this is the merit of the team that put together The Black Book: to have brought the debate regarding twentieth century communism into public discussion; in this respect, as a whole, beyond the reservations that one can hold concerning one page or another, it has played a remarkable role…. To say that the Soviets were worse because their system made more victims, or that the Nazis were worse because they exterminated the Jews, are two positions which are unacceptable, and the debate carried on under these terms is shocking and obscene. 125

Indeed, the challenge is to avoid any “comparative trivialization,” 126or any form of competitive “martyrology” and to admit that, beyond the similarities, these extreme systems had unique features, including the rationalization of power, the definition of the enemy, and designated goals. The point, therefore, is to retrieve memory, to organize understanding of these experiments, and to try to make sense of their functioning, methods, and goals.

Some chapters of The Black Book succeed better than others, but as a whole the undertaking was justified. It was obviously not a neutral scholarly effort, but an attempt to comprehend some of the most haunting moral questions of our times: How was it possible for millions of individuals to enroll in revolutionary movements that aimed at the enslavement, exclusion, elimination, and finally extermination of whole categories of fellow human beings? What was the role of ideological hubris in these criminal practices? How could sophisticated intellectuals like the French poet Louis Aragon write odes to Stalin’s secret police? How could Aragon believe in “the blue eyes of the revolution that burn with cruel necessity”? And how could the once acerbic critic of the Bolsheviks, the acclaimed proletarian writer Maxim Gorky, turn into an abject apologist for Stalinist pseudoscience, unabashedly calling for experiments on human beings: “Hundreds of human guinea pigs are required. This will be a true service to humanity, which will be far more important and useful than the extermination of tens of millions of healthy human beings for the comfort of a miserable, physically, psychologically, and morally degenerate class of predators and parasites.” 127The whole tragedy of Communism lies within this hallucinating statement: the vision of a superior elite whose utopian goals sanctify the most barbaric methods, the denial of the right to life to those who are defined as “degenerate parasites and predators,” the deliberate dehumanization of the victims, and what Alain Besançon correctly identified as the ideological perversity at the heart of totalitarian thinking—the falsification of the idea of good (la falsification du bien).

I have strong reservations regarding theoretical distinctions on the basis of which some historians reach the conclusion that Communism is “more evil” than Nazism. In fact, they were both evil, even radically evil. 128Public awareness of Communist violence and terror has been delayed by the durability of Leninism’s pretense of universality. Because of projection, it took a long time to achieve an agreement that Bolshevism was not another path to democracy and that its victims were overwhelmingly innocent. 129One cannot deny that Communism represented for many the only alternative (in my foreword I discuss a personal family example), especially with the rise of Fascism and of Hitler, at a time when liberal democracy seemed compromised.

Communism was consistently presented as synonymous with hope, but the dream turned into a nightmare: Communism “not only murdered millions, but also took away the hope.” 130Communism was founded upon “a version of a thirst for the sacred with a concomitant revulsion against the profane.” The Soviet “Great Experiment’s master narrative involves the repurification or resacerdotalization of space.” 131This is why Furet, in his closing remarks to Passing of an Illusion , states that upon the moral and political collapse of Leninism we “are condemned to live in the world as it is” (p. 502). With a significantly stronger brush, Martin Malia argued that “any realistic account of communist crimes would effectively shut the door on Utopia; and too many good souls in this unjust world cannot abandon hope for an absolute end to inequality (and some less good souls will always offer them ‘rational’ curative nostrums). And so, all comrade-questers after historical truth should gird their loins for a very Long March indeed before Communism is accorded its fair share of absolute evil.” 132And, indeed, two important registers of criticism directed toward the process of revealing and remembering the crimes of Communist regimes were that of anti-anti-utopianism and anticapitalism. I will not dwell on the validity of counterpoising Communism with capitalism; it is a dead end. It just reproduces the original Manichean Marxist revolutionary ethos of the Communist Manifesto. It is endearing to a certain extent, for one’s beliefs should be respected, but it is irrelevant if we seek to understand the tragedy of the twentieth century. The employment of anti-anti-utopianism in the discussion of left-wing totalitarianism is just another way of avoiding the truth. To reject the legitimacy of the comparison between National Socialism and Bolshevism on the basis of their distinct aims is utterly indecent and logically flawed. Ian Kershaw criticizes arguments based on the

different aims and intentions of Nazism and Bolshevism—aims which were wholly inhumane and negative in the former case and ultimately humane and positive in the latter case. The argument is based upon a deduction from the future (neither verifiable nor feasible) to the present, a procedure which in strict logic is not permissible…. The purely functional point that communist terror was “positive” because it was “directed towards a complete and radical change in society” whereas “fascist (i.e., Nazi) terror reached its highest point with the destruction of the Jews” and “made no attempt to alter human behavior or build a genuinely new society” is, apart from the debatable assertion in the last phrase, a cynical value judgment on the horrors of the Stalinist terror [my emphasis]. 133

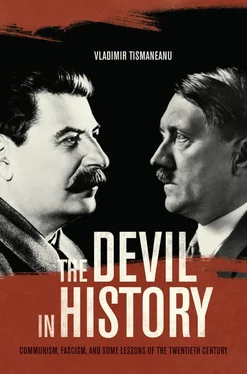

Recognizing Communism as hope soaked in revolutionary utopia is truly a specter to turn away from. This hope materialized as radical evil can only lead to massacre, because “il cherche à s’incarner, et ce faisant, il ne peut faire autrement qu’éliminer ceux qui n’appartiennent pas à la bonne classe sociale, ceux qui résistent à ce projet d’espoir [it looks to take flesh, and doing this, it can only eliminate those who do not belong to the right social class, those who resist this project of hope].” 134Ronald Suny was right in emphasizing that we should not forget that the original aspirations of socialism “were the emancipatory impulses of the Russian Revolution as well.” 135It is difficult to see how this affects the “duty of remembrance” regarding Leninism’s crimes. Not to mention that, as early as 1918, with the Declaration of the Rights of Toiling and Exploited People, the Bolsheviks detailed their ideal of social justice into categories of disenfranchised people (lishentsy) , the prototype taxonomy for the terror that was to follow in the later years. 136Tony Judt puts it bluntly: “The road to Communist hell was undoubtedly paved with good (Marxist) intentions. But so what?… From the point of view of the exiled, humiliated, tortured, maimed or murdered victims, of course, it’s all the same.” 137Furthermore, such shameful commonalities between socialism and Bolshevism should actually be an incentive to call things by their real name when it comes to the radical evil that Communism in power was throughout the twentieth century. The hope that Bolshevism brought to so many was a lie. The full impact of the lie can only be measured by the nightmare of the millions it murdered. The moral and political bankruptcy of the “pure” original ideals cannot remain hidden just for the sake of safeguarding their pristine state. The uproar provoked by the Black Book indicated a “continuing reluctance to take at face value the overwhelming evidence of crimes committed by communist regimes.” 138So many years after the book’s publication, some things have changed, but much more remains to be done. To return to Kołakowski’s metaphor, the devil not only incarnated itself in history, it also wrecked our memory of it.

Читать дальше