These proposals, of course, were fragmentary. Many of them were inevitably driven by tactical considerations, and in any case, there is always a great divide in politics between theory and practice. It is impossible to say whether Goerdeler’s proposals would have been adopted if a coup had succeeded. Thus they are primarily of interest for what they reveal about the two primary goals of Goerdeler’s group, namely the far-reaching depoliticization of government and the overcoming of political fragmentation by forging a new sense of community. The Weimar Republic cast as long a shadow over these objectives as it did over the Hitler years. An underlying feeling of helplessness pervades these proposals. When Goerdeler remarked that he wanted to pursue the “German way” in drafting his constitution and would not allow himself to be “led astray” by Western models, he inadvertently disclosed an intellectual detachment and isolation that the entire German resistance never overcame. In the end, however, Goerdeler was not motivated by the desire for social and constitutional change embodied in these proposals, nor did he justify himself by them. They were produced under great pressure and emotional stress and were often not fully developed. To understand Goerdeler we have to look to more compelling forces. 18

* * *

Quite different from the Beck-Goerdeler-Popitz group, and yet in some ways strangely similar, was the other important group of civilian opponents of the Nazi regime. It was founded and held together by Helmuth von Moltke, a great-grandnephew of the celebrated army commander of the Franco-Prussian War, who worked in the Wehrmacht high command as an expert in international law. His group was later dubbed the Kreisau Circle after the estate owned by the Moltke family in Silesia, although it met there only two or three times. Its intense discussions, conducted in working groups, took place more frequently in various locations in Berlin; beginning in early 1943 most were held on Hortensienstrasse in Lichterfelde, at the home of Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, another bearer of a famous name in Prussian history. Related to both Moltke and Stauffenberg, he was a lawyer and officer who had been assigned to the eastern department of the Defense Economy Office. While Moltke has been described as the “engine” of the group, Yorck von Wartenburg was its “heart.” 19

Around Moltke and Yorck gathered what at first glance appeared to be a motley array of strong-willed individuals with markedly different origins, temperaments, and convictions. Among them was Adam von Trott zu Solz, a descendant, on his mother’s side, of John Jay, the first chief justice of the United States. Trott had been a Rhodes scholar and had many friends in England, including the so-called Cliveden set around David Astor. Like Hans-Bernd von Haeften, another member of the circle, Trott was employed in the Foreign Office. Striving to include experts from as many areas of political and social life as possible, the Kreisau Circle recruited Horst von Einsiedel, a Harvard graduate and an expert in economics. Carl Dietrich von Trotha, on the other hand, was a cousin of Moltke’s, born in Kreisau, and had been, like some other members of the group, a student of the philosopher and sociologist Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy.

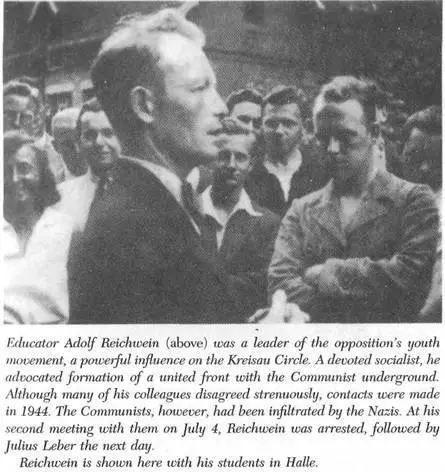

The most striking characteristic of this group, apart from its strong religious leanings, was its earnest and quite successful attempt to attract a number of devoted but undogmatic socialists. Among them was the educator Adolf Reichwein, who came from the Romanticist youth movement of the 1920s and had met Einsiedel and Moltke in one of the reform-minded volunteer work camps. Through Reichwein, Theodor Haubach also joined the group. A former student of Karl Jaspers and Alfred Weber, Haubach was nicknamed The General by his friends because of his expertise in military policy. He also had a deep interest in philosophy and the arts and had served as chief press officer of the Prussian government for several years.

Haubach, in turn, recruited the man who was possibly the most colorful, emotional, and powerful figure in the circle, Carlo Mierendorff, a close friend since their school days in Darmstadt. Like Haubach, Mierendorff had a background in literature; before finally devoting himself entirely to politics, he had dabbled in the expressionist movement and edited a magazine. According to another acquaintance, the writer Gerhart Hauptmann, he was a “born leader.” Within the Social Democratic Party he was one of the young rebels who look on the complacent party hierarchy and its outdated programs and slogans. Mierendorff was arrested shortly after Hitler took power and spent five years in concentration camps, where at one point he was delivered by camp authorities into the hands of Communist fellow prisoners, who beat him nearly to death. During this time Haubach sought constantly to obtain the release of his friend, succeeding even in reaching Adolf Eichmann. (Never, he later said of Eichmann, had he seen “such glassy green eyes.” 20)

A number of figures from the Christian resistance also joined the Kreisau Circle, including the Jesuits Alfred Delp and Augustin Rösch, as well as prominent Protestants like the theologian Eugen Gerstenmaier and the prison chaplain Harald Poelchau. Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg and Julius Leber were also loosely affiliated with this group. They were older and more experienced than the others, with too much of the politician in them to be interested in sharing the circle’s passion for theoretical debates. “What comes later will take care of itself,” Leber was fond of saying. True to type, he struck up an immediate friendship with Stauffenberg-who was always pressing for more action-when the two met in late 1943.

What brought the Kreisau group together was not principally a determination to overthrow the Nazi regime but rather the common project of planning, through their preparatory discussions, what a modern, post-Hitler Germany would look like. In this way “they kept themselves alive,” according to a close observer. 21There was a strong utopian streak in their thought and planning, which was infused with Christian and socialist ideals, as well as remnants from the youth movement of a romantic belief in the dawning of a new era. They basically believed that all social and political systems were reaching a dead end and that capitalism and Communism, no less than Nazism, were symptomatic of the crisis deep and all-encompassing in modern mass society.

This lofty radicalism, often quite remote from the real world, was the main source of discord between the Kreisau and Goerdeler groups. The former accused the “old-timers” of being stuck in outmoded patterns of thought. Instead of seeking a genuinely new beginning, the Goerdeler group wanted merely to avoid the missteps that had been revealed by the failure of the Weimar Republic. The birth of a “new age,” on the other hand, required an entirely fresh approach. Moltke spoke contemptuously of “that Goerdeler mess” and, like Delp, cautioned opponents of the regime who were looking for like-minded contacts against any involvement with what he called “their reactionary Excellencies.” 22

The two groups had more in common, however, than they ever imagined. They were both deeply enamored of the curious German tradition of grand, sweeping critiques of entire civilizations. The main difference lay in the fact that the Goerdeler group translated its ideas into more or less practical programs for action (which were by no means free of inconsistencies), while the Kreisau group moved in more theoretical and idealistic spheres, launching ideas that only occasionally led to concrete solutions. Both groups considered mass society the great scourge of the time, and both sought to replace it with a “community” of some kind-markedly more Christian in the case of the Kreisauers, although still not without an authoritarian streak. Both groups were eager to recover the lost “organic” communities of the past, which in their view still retained something of the Garden of Eden, and both were appalled by the egalitarian tendencies of the time.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)