Carl Goerdeler himself can be taken to illustrate this phenomenon. There is every reason to believe that he was closely involved in the draft constitution put forward by Ulrich von Hassell and Johannes Popitz, both senior officials in earlier governments, in early 1940. Under this plan, a three-person council would assume executive power after the Nazi dictatorship had been overthrown, with Beck as its leader, and a constitutional council would be formed to restore “the majesty of the law.” Although the draft constitution clearly stated that this regime, quasi-dictatorial at best, would only be temporary, no termination date was specified and no mention was made of elections.

Goerdeler’s counterproposal illustrated his unmitigated but perhaps misguided faith in reason, he suggested holding a plebiscite us soon as possible so as to give the new regime a solid popular base. His friends firmly rejected this proposal on the grounds that the corrupting effects of the Hitler years would still be felt for a considerable period so that it would be foolish to submit the new order to the peoples will too hastily. Once again, however, Goerdeler was dissuaded from an authoritarian approach by his stubborn belief in the good judgment of humankind. He continued to insist, despite well-founded doubts on all sides, that if the truth about the Nazis could be freely spoken for “only twenty-four hours” their myopic followers would suddenly see the light. The same kind of reasoning led Goerdeler to argue that the NSDAP should not be prohibited under the new order.

Differences of opinion about the transitional regime remained. The political scientist Jens Peter Jessen and the lawyer Carl Langbehn, who advised the conspirators on their plans, added a sharply worded clause to the draft providing for a time limit on the state of emergency. The conspirators generally agreed, however, that all criminal acts committed under the Nazi regime should be severely punished: the “sword of justice,” as Goerdeler later wrote, adding to the typical bombast of the times his own touch of the country pastor, must “mercilessly strike down those who have corrupted the fatherland into a caricature of a nation.” Mere membership in Nazi organizations would not be punishable under this plan, though, and anonymous denunciations would be inadmissible in court. The conspirators also planned a law to rectify past injustices, especially toward Jews. A dubious feature of this law, however, was a set of provisions that recognized the citizenship of Jews whose families had long been established in Germany but that called for every effort to be made to enable more-recent Jewish immigrants “to found a state of their own.”

The modifications that the conspirators’ thinking underwent over the years is also evidenced in the fate of a plan Goerdeler and some of his advisers originally advanced to restore the monarchy. They were by no means royalists; rather, their intent was to establish an institution that would be universally accepted and remain above the fray of daily political life as the British and Dutch monarchies were. It seems that tactical considerations also played a role in their proposal: the conspirators hoped thereby to win the support of conservatives, especially within the officer corps. In the course of many lengthy debates, various names were considered as possible pretenders to the throne, but in the end the entire subject was dropped when it met with passionate opposition from Helmuth von Moltke’s Kreisau Circle.

Many variants of Goerdeler’s constitutional plans have survived, indicating both his openness to new ideas and the influence of changing advisers. But the core of his plan, which eventually took shape after a rather nebulous start, was always a strong government in which various “corporatist bodies” played a leading role while the parliament was limited to a more or less supervisory function. This basic thrust found expression in a considerable expansion of self-government at even the lowest levels of society; not only municipalities but universities, student bodies, churches, and professional organizations would be involved. To the end of his life, Goerdeler clung to the belief that this was the genuine “German way” in politics, which had proved itself even amid the confusion of the Weimar years and despite “extreme democratization” and “extensive corrosion by political parties.” The various states within Germany he reduced to little more than large administrative units, seeing them as an intermediate level of government that was not really close to everyday life and yet too far removed from the focus of real power.

In the same spirit, Goerdeler attempted to limit the influence of the general public, especially through political parties, and to turn the decision-making process over to indirectly elected bodies whenever possible. One of the clear contradictions between Goerdeler’s theory and his practice was that, despite his belief in the power of reason, he never entirely freed himself from the fear he had acquired in the Weimar years of what ordinary people might do. Notions such as “the power of parties,” “splinter parties,” and “self-interested parties” continued to haunt his own constitutional thinking as well as that of the entire group.

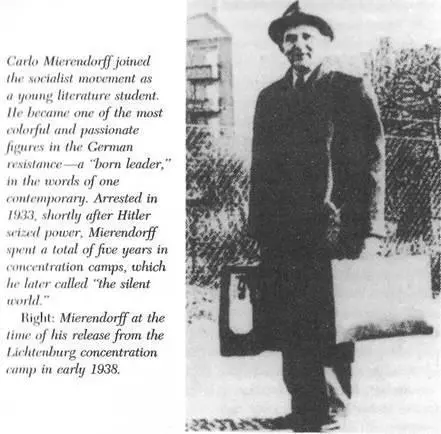

The election process was therefore calculated to bring forth strong, experienced “personalities with roots in real life” by means of a complicated modified majority-rule system. It is noteworthy that all the opposition groups agreed on this, despite their strong differences on other questions. The socialist Carlo Mierendorff said “never again shall the German people lose their way amid the squabbling of political parties,” and his fellow socialist Julius Leber called for an end “to the old forms of party rule.” It was he who summarized as follows the argument against proportional representation, which he blamed most of all for creating political fragmentation: “It fails totally to carry out its real functions, namely, selecting suitable men and maintaining the trust between the people and the leadership. Instead, it simply imposes on politics the determined dullards who eventually rise to the top of party hierarchies.” 16Goerdeler even contemplated a drastic limitation on majority rule by restricting seats in the parliament to the three strongest parties.

Another suggestion for the new order would have conferred a double role on fathers with at least three children. Other plans for reform reflected the strong corporatist tradition in German society. Goerdeler, for instance, wanted to see a Reichsständehaus, an upper house consisting of fifty respected appointees as well as representatives of the churches, universities, artists’ guilds, and, most important, labor unions, for whom he had particularly high expectations, certainly far higher than he did for political parties. He had learned in his years as mayor of Leipzig that involvement in everyday life soon dispels the doctrinaire theories that in his view were badly damaging political life or even destroying it.

Goerdeler also advanced some suggestions about how the economy should operate: he advocated moderate liberalism, limits on the role of industry (a stricture that clearly reflected the influence of the Freiburg school), participation of workers in corporate management, and a sense of social responsibility on the part of the propertied classes. There were many thoroughly antimodern aspects to Goerdeler’s proposals, which were as passionately opposed to the egalitarian tendencies of contemporary industrial societies as they were to pluralistic social and political interests. Goerdeler wanted to bring all these contending interests together within an idyllic, community-based order that served the general interest. Thus there was a definite Utopian cast to national-conservative thought, an inclination to idealize the “good old days” even though, as everyone knows, they were never all that good. Nevertheless, these efforts cannot be dismissed as mere attempts to restore the lost societies of the past. Goerdeler’s close working relationship and even friendship with trade union leaders such as Wilhelm Leuschner and Jakob Kaiser points to the contrary. Indeed, the first people to accuse Goerdeler of being “reactionary” were, in a remarkable twist, the most conservative members of the group-Hassell, Jessen, and Popitz-who denounced Goerdeler’s proposals for going too far toward restoring democratic “Weimar” conditions. 17

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)